Abstract

The work of Paulo Freire (1921–1997) is seen by many educators as topical and urgent to rethink pedagogy today. Furthermore, it inspires many contemporary artists through its use of visual materials. This article aims to investigate the various links – from different perspectives – between the work of the Brazilian pedagogue and art.

In the first part, the text focuses on the images produced by artists especially for Freire’s literacy actions in Brazil in the 1960s and their use as illustrations of ‘generative themes’ in order to facilitate both literacy and critical consciousness [conscientização].

A second part of the text looks into the perception of art by Freire and into the way he identified several similarities between pedagogy and art. This allows to put his rather classical approach of art as a discipline into perspective with his writings that played a key role in the emergence of the notion of dialogue-based art and critical gallery education.

Three examples of artistic practices (from Rollins + K.O.S., Ultra-Red, De Andrade) directly borrowing concepts and tools from the Freireian pedagogy are then presented.

The article concludes by highlighting the way Freire’s writings have been called up in contemporary artistic spheres – in particular by critical gallery educators – and how it could be implemented in the field in future.

PROBLEM-POSING ART: FROM GENERATIVE IMAGES TO A FREIREAN APPROACH OF ART

In the literacy processes developed by the Brazilian pedagogue Paulo Freire (1921–1997), visual material played a key role. The educators involved in the project – consisting of a series of exchanges with the population of a given geographical area – produced ‘coded pictures’ that facilitated a literacy process aiming at political conscientization through a generative process. Freire thought that, in the pedagogical exchange, any existing work of art could be used as a way to trigger a discussion about the socio-political conditions of its production and, by extension, about the conditions experienced by the learners.

Freire saw similarities between the work of the teachers and that of the artists – in the classical sense of giving life to an object by reshaping raw material. This article looks at this perception of art by Freire and discusses how – even though he was not especially in contact with contemporary artists during his life – his theory played a key role in the emergence of a dialogical art (and a critical gallery education) that expanded the field of artistic practices beyond the conception of art that Freire himself had.

The first part focuses on various discussions that Freire took part in, around the notion of art and its links to pedagogy. The second examines three case studies showing how artists reengaged with Freire’s thinking (during his lifetime and after). Those artistic projects are examples of a form of dialogical art – an art that, according to several art historians, is tributary to Freire’s thinking. The final part highlights the way Freire’s writing has been called up, in contemporary artistic spheres – in particular by critical gallery educators – both to analyze the transformation of higher education in the 2000s and to plot alternatives, in connection with the ‘Educational Turn in curating’.

Art As A Generative Pedagogical Tool For Conscientization

Freire (2005, p. 47) tackled pedagogy as a tool to overcome oppression, through conscientization. In the first pages of Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he wrote: ‘To surmount the situation of oppression, people must first critically recognize its causes, so that through transforming action they can create a new situation, one which makes possible the pursuit of a fuller humanity.’ And to do so, he proposed ‘a pedagogy which must be forged with, not for, the oppressed … in the incessant struggle to regain their humanity’.

In the third chapter of this seminal book, Freire (2005, pp. 87–124) describes a quite detailed plan for establishing a dialogical form of pedagogy, taking the example of literacy campaigns that were led under his supervision in rural areas of Brazil’s Northeast region during the 1960s. The pedagogical process begins with a search for a meaningful theme for oppressed learners: the generative theme. In order to identify this theme, an interdisciplinary team of researchers (involved in art, education, sociology, political studies) undertakes field trips and, through conversations with the inhabitants (who are invited to take part in meetings and become assistants in the research), as well as observations of even seemingly insignificant factors, the team members ‘set their critical “aim” on the area under study, as if it were for them an enormous, unique, living “code” to be deciphered’ (Freire, 2005, p. 111).

In a second phase, the researchers share their accounts, with each other and with the representatives of the population, during appraisal meetings. The sharing of observations and the discussions enable the identification of a nucleus of contradictions that sits at the heart of daily life for the inhabitants in the studied area.

Next, and this is where the visual dimension comes into play, the team uses these contradictions as the basis to produce codifications (mainly sketches, paintings or photographs) that will function as pedagogical tools to identify the generative themes (whose analysis will enable the learners to develop a critical reflection about the world in which they live).

These pictures must ‘necessarily represent situations known to the individuals whose themes are being sought’ (Freire, 2005, pp. 103–104) and must function ‘as challenges upon which to bring a critical reflection’ (Freire, 2005, pp. 103–104). Freire recommends various forms for this codification, which may be visual, pictorial, graphic, tactile or audible, depending on ‘the subject to encode, but also on the individuals to which it is addressed, according to whether they have experience of reading or not’ (Freire, 2005, p. 112).

The ‘pictures’ are then ‘decoded’ as part of the ‘educational program’ itself. This decoding must enable the participants to generate new visions of the world they live in, to review their fatalism and to foster the emergence of an ‘untested feasibility’ (Freire, 2005, p. 102), that is, a hitherto unimaginable action that may be accomplished.

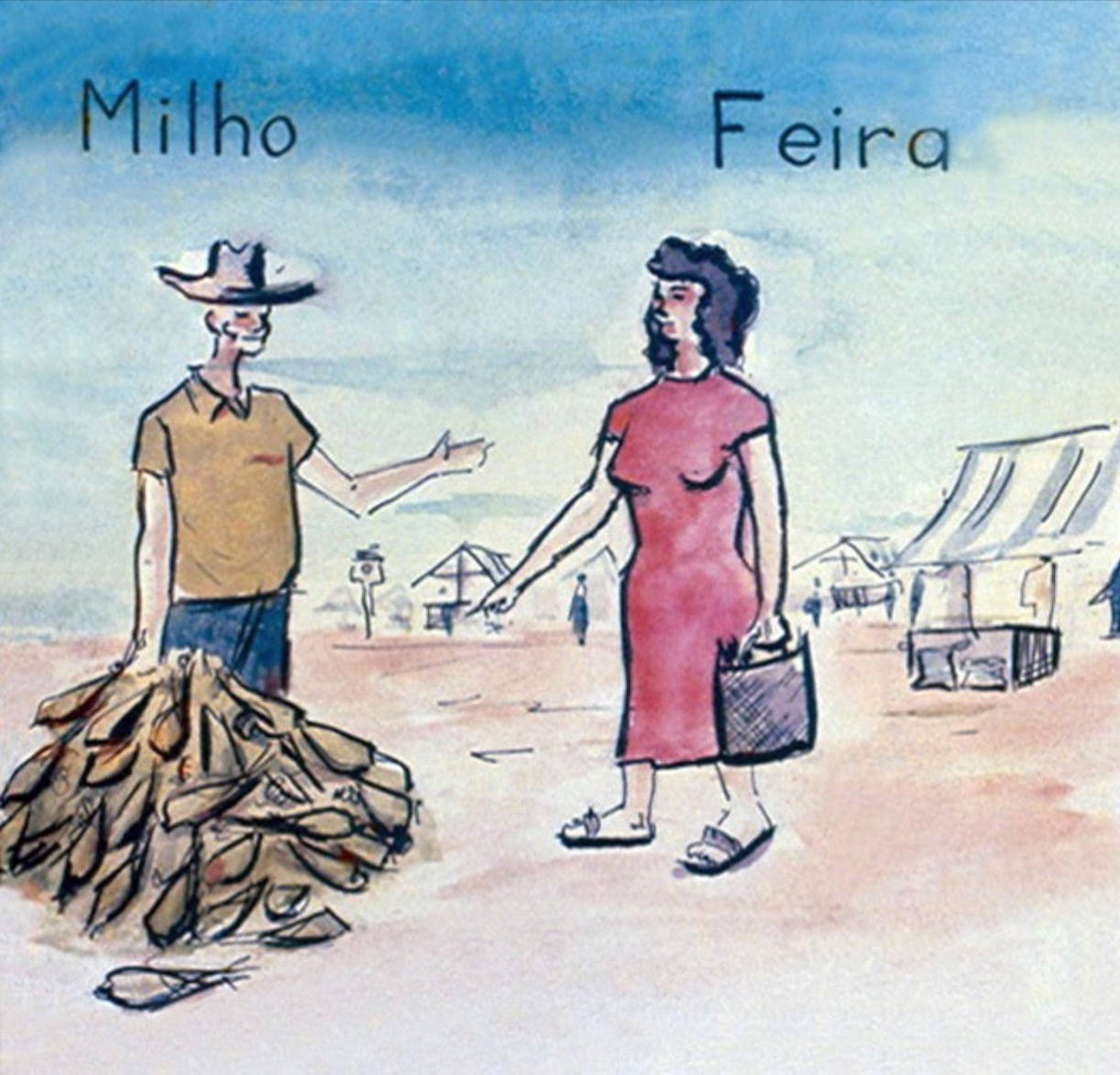

That system was first tested in Angicos (State of Rio Grande do Norte) in 1963 (Fávero, 2012, p. 466; Gadotti, 2014). There, a first series of slides was used. According to Antonia Terra (1994, p. 156), those images (depicting women and men undertaking activities traditionally assigned to them in a stereotypical and non-problematized manner) were realized by a Christmas card designer.

That same year, Freire and his team were commissioned by the Brazilian authorities to develop a nationwide literacy plan, opening 2,000 cultural circles in which to develop a similar approach. The following year, however, the military coup put an end to the project, as Freire was imprisoned (he would later flee to Bolivia).

Nevertheless, some of the visual material produced from the first experiments has survived until today. A representative example of this material can be seen in the diapositive set produced in 1964 for the aborted Programa Nacional de Alfabetização’, following the ‘Freire system of education’ (Sistema de Educação Paulo Freire).

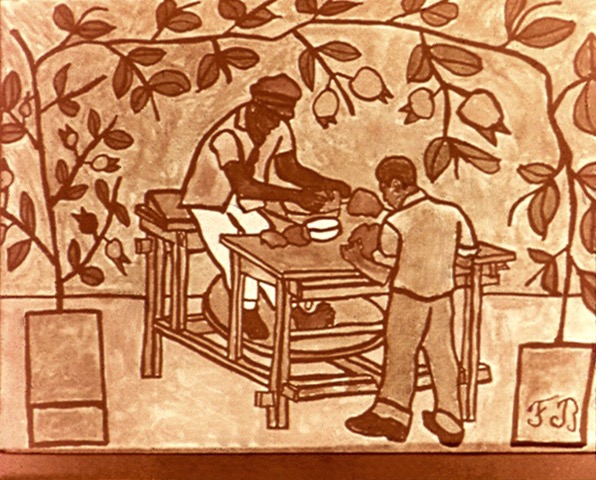

This set is the third version of visual material produced for that literacy campaign and contains ten drawings by the Brazilian artist Francisco Brennand (Fávero, 2012, p. 476). These compositions are realized in a popular style and the line is quite simple. They illustrate everyday situations experienced by people living in rural areas and, in particular, highlight the question of the link between human beings and their environment.

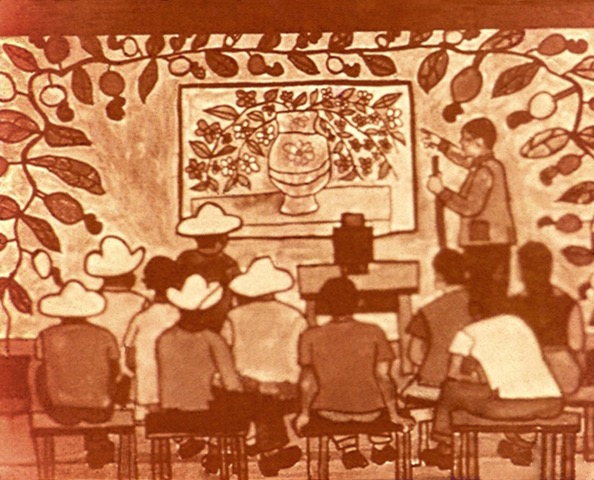

The two last images depict a poetry book, opening on to another kind of activity that should be available to learners, if one follows Freire’s approach. Those last slides work as a kind of mise en abyme of the literacy process, with a scene describing a circle around one of the other drawings in the series, displayed and commented on by an educator in front of a group.

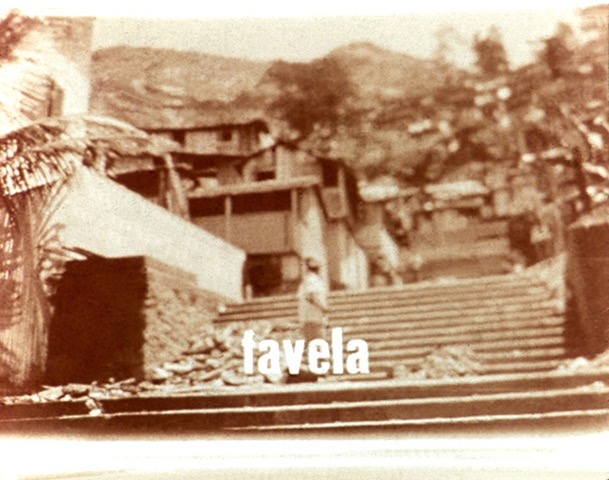

Those slides could serve as starting points for discussion and for identifying themes that need to be discussed. In that way, they can be seen as tool for conscientization, for learning the world, as much as for literacy. The other slides are rather directed toward learning the word, toward literacy. They are split into seventeen series, each organized around a specific word. In each series, the first slide is of a photograph illustrating a word superimposed on it (a photograph of a favela, with ‘favela’ typed on it).

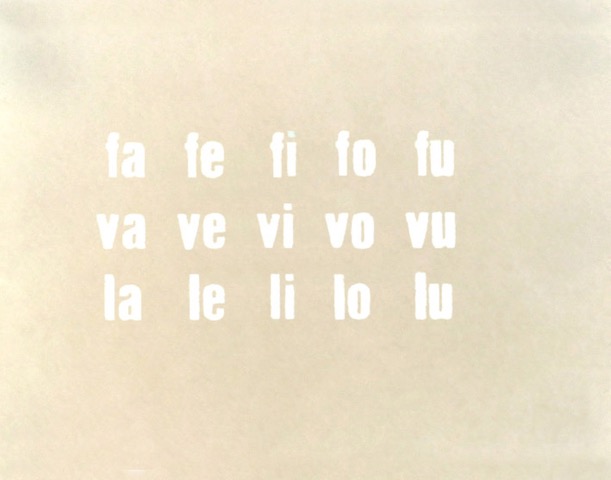

On the next slide, the same word is written on a uniform background, becoming an abstraction. Then, it is decomposed into syllables, separated with dashes (fa-ve-la). Further, we find individual slides building groups of syllables beginning with the syllables composing the initial word (fa-fe-fi-fo-fu / la-le-li-lo-lu). A final slide puts together all the syllables that can be made from the initial word (fa-fe-fi-fo-fu-va-ve-vi-vo-vu-la-le-li-lo-lu).

It is somehow paradoxical to use a fixed collection of slides to illustrate an approach that Freire (1998, pp. 30–31) constantly refused to name ‘a method’.

Nevertheless, even though he described the way each context should produce the content of the pedagogical exchange, this ‘kit’ is an indication of how the ‘Freire sistema’ was meant to be expanded and gives a good idea of the way visual material was used. Moreover, the choice of a professional and recognized artist to produce the material confirms the importance given to the artistic dimension.

Freire’s Idea Of Art

In Pedagogy of Hope. Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire (1994) relates an anecdote which gives us an initial idea of how he considered art. He explains how Flávio, the son of his friend Claudius Ceccon 1 was plagued by a violent feeling of injustice during an episode that happened around a drawing exercise in the Swiss school he was attending. Flávio returned home sad and discouraged as his teacher had torn one of his drawings into pieces. His father asked to meet the teacher and during the exchange that followed she praised Flávio’s talent and autonomy. She also proudly showed Ceccon a series of almost identical cat drawings produced by Flávio’s fellow pupils, observing a small sculpture. She explained that she was trying to avoid situations – terrifying for the children, according to her – where they have to make choices, to make decisions and to create something new. That’s why she couldn’t accept Flávio’s cat, which was drawn with ‘impossible colors’. For her, letting him follow that direction would have been harmful, not to him – a free spirited and intelligent child – but to the others.

Freire (1994, p. 143) writes quite extensively about this anecdote and sees it as a metaphor of the school system itself:

And that, it appeared, was the way the entire school functioned. It was not merely that one educator who shook with fear at the very mention of freedom, creation, adventure, risk. For the whole school, as for her, the world should not change […]Blaze trails as we go? Re-create the world, transform it? Never!

Through this anecdote, we can read that Freire advocated for a use of drawing and art in the pedagogical system as a tool not to simply observe existing, or to produce beautiful, objects, but to experiment, create and produce new imaginaries for the world.

Moreover, Freire considered that the work of the educator herself or himself could be compared to that of the artist, in at least two different writings. The first was in a dialogue with Ira Shor (Freire & Shor, 1987), in which the two critical educators exchange ideas about the role of art in transformative teaching. Shor (Freire & Shor, 1987, p. 115) proposes that teaching can be seen as an aesthetic activity, if one considers the classroom as a plastic material that can be reshaped constantly. In addition, bringing a theme identified by a student or a societal subject to the class for inquiry (in a ‘problem-posing’ approach and through a process of codification, as defined by Freire) is, according to Shor, an artistic process. For him, ‘creative ingenuity’ is needed to ‘adjust the pedagogy for each new group of students’ and, moreover, the act of disrupting passive education is an aesthetic moment ‘because it asks the students to reperceive their prior understandings and to practice new perceptions as creative learners with the teacher’ (Freire & Shor, 1987, pp. 115–116). Therefore, he sees the classroom as a space for performance, with dialogical, visual and auditory dimensions. Freire (Freire & Shor, 1987, p. 118) answers: ‘I agree absolutely with you about this question of the teacher as an artist’ and explains that he sees education as a permanent process of formation, shaping the students and helping them to grow up. He adds: ‘This process is necessarily an artistic one. It is impossible to participate in the process of getting shaped, which is a kind of rebirth, without some aesthetic moments. In this aspect, education is naturally an aesthetic exercise’ (Freire & Shor, 1987, p. 118). He goes on to say: ‘For me, knowing is something beautiful! To the extent that knowing is unveiling an object, the unveiling gives the object “life”, calls it into “life”, even gives it a new “life”. This is an artistic task because our knowing has a life-giving quality, creating and animating objects as we study them’ (Freire & Shor, 1987, pp. 118–119).

For Freire, the relationship between the students and the teacher is necessarily an aesthetic (and political) one and being aware of that dimension can help one to teach better. In this exchange, it can be seen that art is tackled mainly as an aesthetic activity that one ‘brings to life’. Even though the performative dimension is also underlined, other dimensions of art (conceptual, discursive, critical or transformative in particular) are not mentioned. Therefore, the metaphor of the teacher as an artist is based on a classical view of art that is not fully in line with the contemporary art practice of the time (which, paradoxically, for some of them includes borrowing tools directly from Freire’s approach, as we will see in the next section).

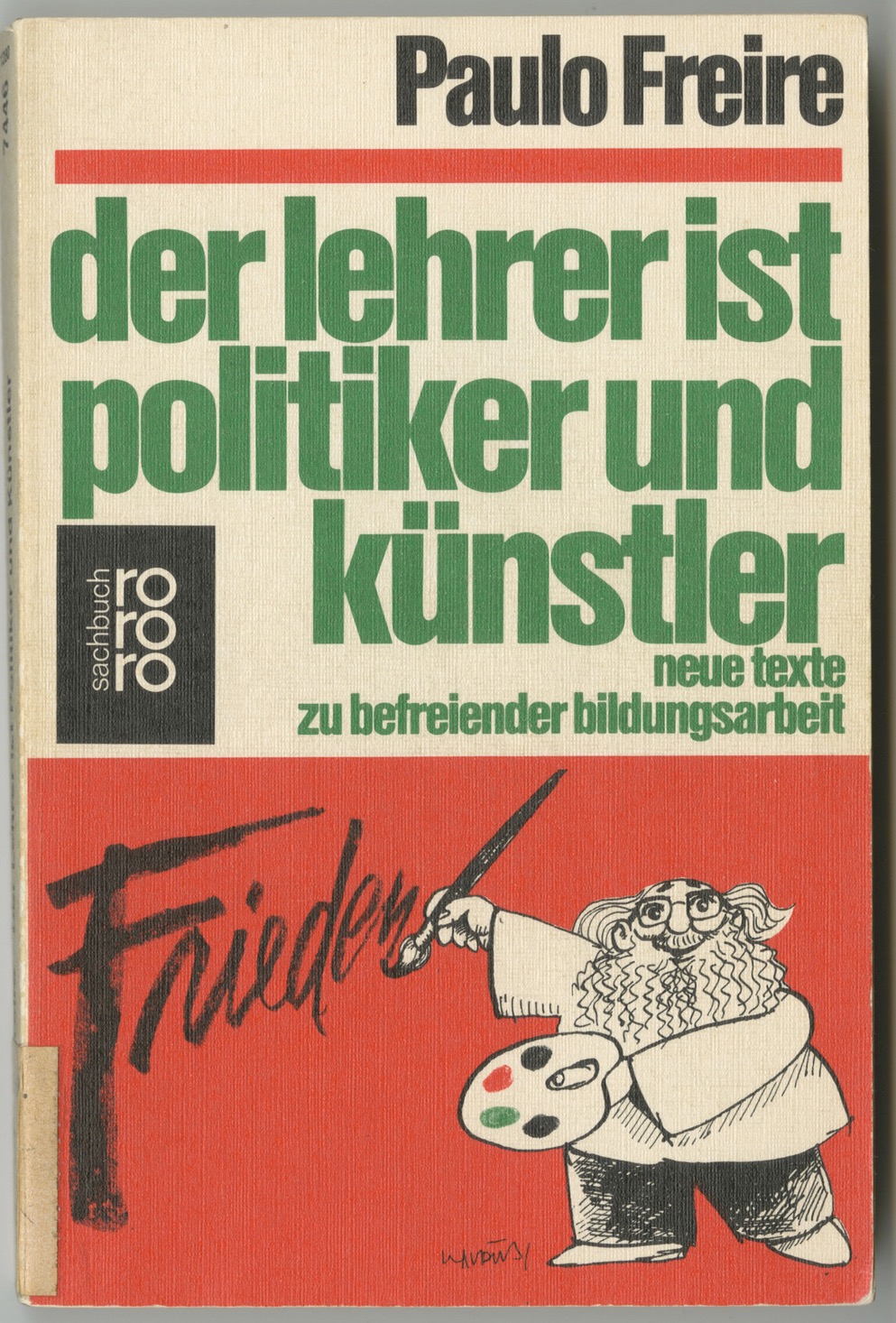

In the other case, and almost ten years before this exchange with Ira Shor, Freire was already defending, in an interview, the artistic dimension of teaching. Answering the question – whether the political dimension of education was a specificity of the Brazilian context – he answered: ‘Being together the educator and the politician is not a privilege of Brazil! I am convinced about this. As educators we are politicians and also artists’ (Freire, 1978, p. 272). Interestingly – because the debate continues to be very topical 2 – he presents the political and artistic dimension of teaching as a way to oppose the alleged neutrality of teaching, which is for him a hidden ideology preventing teachers from analyzing concrete reality in a critical way. The choices made by the teacher (through the aesthetic performance of teaching mentioned before) could then be seen as a way to defend a specific political position and to reject any kind of supposedly neutral approach.

This idea of claiming an artistic dimension of teaching seems to have found some resonance during Freire’s lifetime. For example, one of the earliest collections of translations of Freire’s work in German was entitled ‘Der Lehrer ist Politiker und Künstler’ [The Teacher is a Politician and an Artist] (1981) (with a cover illustration by Claudius Ceccon depicting Freire as a painter), even though the idea is not developed in the book but only presented through the translation of the few lines about this idea from the 1978 interview mentioned above.

Just before he passed away, Freire gave one of his last interviews to Tom Finkelpearl, then Program Director of PS1 Contemporary Art Center in New York City. In this interview (Finkelpearl, 2000, p. 288), Freire explains that, for him, any artwork – whether it is political or not – can be a tool for a ‘problem-posing’ educational approach and, as such, can provoke political discussions. He explains that, without instrumentalizing the artists, their production can be used independently from their initial intentions and purposes. He gives the example of a still life painting, which can elicit a discussion on the right of anybody to access beauty.

But in discussing beauty, you can easily discuss ethical questions, because of the relationship between ethics and aesthetics. In discussing ethics and aesthetics, you discuss politics. For example, you can discuss the right to beauty, the right poor people have to be beautiful, to have beauties, to create beauties.

Freire states that in any art production, the artist cannot escape the social dimension of their own existence and that, consciously or not, they transfer their own social, political and ideological influences onto the work, providing the viewer with elements that can be used to open a debate on those issues.

Thus, he claims that any work of art can be useful to support his dialogical and political pedagogical approach, not only artworks whose content would be politicized, but also works that might be produced in a dialogical manner.

Indeed, Freire didn’t seem to be aware of the dialogical art practices developed by artists, some of whom had been imbued with his theory from the beginning of the 1980s. Hence, when Finkelpearl mentions, in the interview, the work of Mierle Laderman Ukeles in collaboration with the New York City Department of Sanitation, he discovers it for the first time (and finds the idea of following the workers’ choreography beautiful, showing an open-mindedness toward considering everyday experience as art). He also shows enthusiasm for the murals he encountered during a trip to Chicago, where he met John Weber (1979), a member of the Chicago Mural Group, who told him about the notion of ‘community art’.

Using Freire To Define A New Kind Of Art Practices: Towards A Problem-Posing Art

The Finkelpearl interview can be seen as a turning point in the discussion about the links between Freire and art, in several regards. First, it is a very rare example of a comment by the pedagogue on contemporary art practices. It is the last time he will talk about art and – to our knowledge – the occasion in which he discusses the subject most extensively. And most importantly, Finkelpearl uses his exchange with Freire as a way of illustrating a new kind of artistic practice that he is one of the first to theorize and to promote. In the introduction to the interview, and in order to defend artists who put exchanges with non-artists at the heart of their work, Finkelpearl (2000, p. 272) presents Freire’s dialogical pedagogy as a counterpoint to the, still, largely shared Greenbergian idea of aesthetics being autonomous and isolated from the world because it only addresses issues inherent to the artwork itself. Thus, Freire’s approach allows Finkelpearl (2000, p. 278) to anchor the artistic practices he is promoting in another theoretical tradition.

In particular, the author compares the definition of banking education (Freire’s expression; 1970b, pp. 71–72) to describe traditional teaching where knowledge is accumulated in learners’ heads (which are compared to ‘empty bottles’), with the usual relationship between the artist and his passive audience:

This dialectic can be applied to the artist–audience relationship. In the context of the museum (the equivalent of the school), artists, through their work, often take on the role of moral/intellectual/aesthetic teachers, while the audience takes on the role of the passive student. And in the narrative structure of the museum, artwork can become ‘lifeless and petrified,’ dead in the mausoleum. Of course this does not need to be the case.

For him, a dialogical approach to art should help to transform this relationship into an active and critically minded one. Finkelpearl thus calls for the engagement of artists and institution directors to enable a change in that direction, insisting that Freire’s approach requires long-term involvement that a few community meeting sessions couldn’t replace.

Finkelpearl (2000, p. 283) uses Freire’s approach to describe what he sees as a fundamental change in art practice:

Freire’s emphasis on process and transformation is relevant to the art discussed in this section of the book [Five Dialogues on Dialogue-Based Public Art Projects], an art in which process and product are one. This is essentially different from traditional works that are created out of sight of the audience – finished and stable, created for the autonomous, permanent, unchanging context of the museum. Just as Freire questions education that seeks to transmit a set of immutable facts from teacher to student, the artists discussed in this section question the one-way communication between artist and audience, and create art through a problem-posing process.

Through the idea of ‘problem-posing’ Finkelpearl lets us glimpse a new definition of the practices that he sees emerging.

After this text was published, many authors interested in dialogical art (or socially engaged art practice, or community practices, depending on the terminology used) as well as in critical gallery education, began to underline the key role played by Freire’s thinking for those practices, which became ever more common and institutionally recognized. 3

The art historian and critic Grant Kester (1999, p. 19) begins a text about ‘discursive practices’ by writing:

In many cases these works challenge the distinction between artist and audience, turning viewers into co-participants. They replace the conventional, ‘banking style’ of art (to borrow a phrase from Paulo Freire), in which the artist ‘deposits’ his or her expressive content into a physical container to be ‘withdrawn’ later by the passive viewer, with a process of dialogical exchange and collaborative interaction.

In Artificial Hells. Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship (2012, pp. 266–267), the art historian Claire Bishop presents Freire as one of the key thinkers to understand what she names ‘participatory art’: ‘Freire’s pedagogic projects framework applies equally to the history of participatory art I have been tracing through this book: a single artist (teacher) allows the viewer (student) freedom within a newly self-disciplined form of authority.’

The gallery educator Felicity Allen (2008), willing to ‘situate gallery education’, opens a 2008 text with a quotation by Freire about the impossibility for one person to ‘deposit’ ideas in another person’s mind.

In 2011, in a book aiming to provide tools to educators willing to train socially engaged artists, the artist and gallery educator Pablo Helguera (2011) writes: ‘Freire’s approach provides a path to thinking about how an artist can engage with a community in a productive collaborative capacity.’

The same year, critical gallery educator Carmen Mörsch (2011) qualified the kind of gallery education that she calls ‘deconstructivist’ and ‘transformative’ in these terms:

The primary educational objective is the development of a critical attitude […]. Methods borrowed from artistic procedures are applied more often here […] the transformative methodological instruments are also oriented towards strategies of activism and towards the epistemologies and methods of critical pedagogy – with a special reference to Paulo Freire.

Through those examples, which could be accompanied by others, one can see how, after his death, Freire became a key reference for many thinkers in the art world, and how his theory was used to highlight and define the specificities of a new kind of art and of gallery education practice.

In the next section we focus on how his thinking was practically reengaged by artists/educators working in the field of art. We focus on artists quoting Freire directly, even though ‘dialogical art’ or ‘deconstructive/transformative gallery education’ also include the practice of artists or educators who do not refer directly to the Brazilian pedagogue.

The three case studies that follow describe practices spread over a 30-year span (beginning more than fifteen years before Freire’s death), which propose very different approaches in terms of collaboration and results. However, all are deeply connected to Freire’s work.

Artists Reengaging Freire

Reclaiming the Word: Tim Rollins + K.O.S.

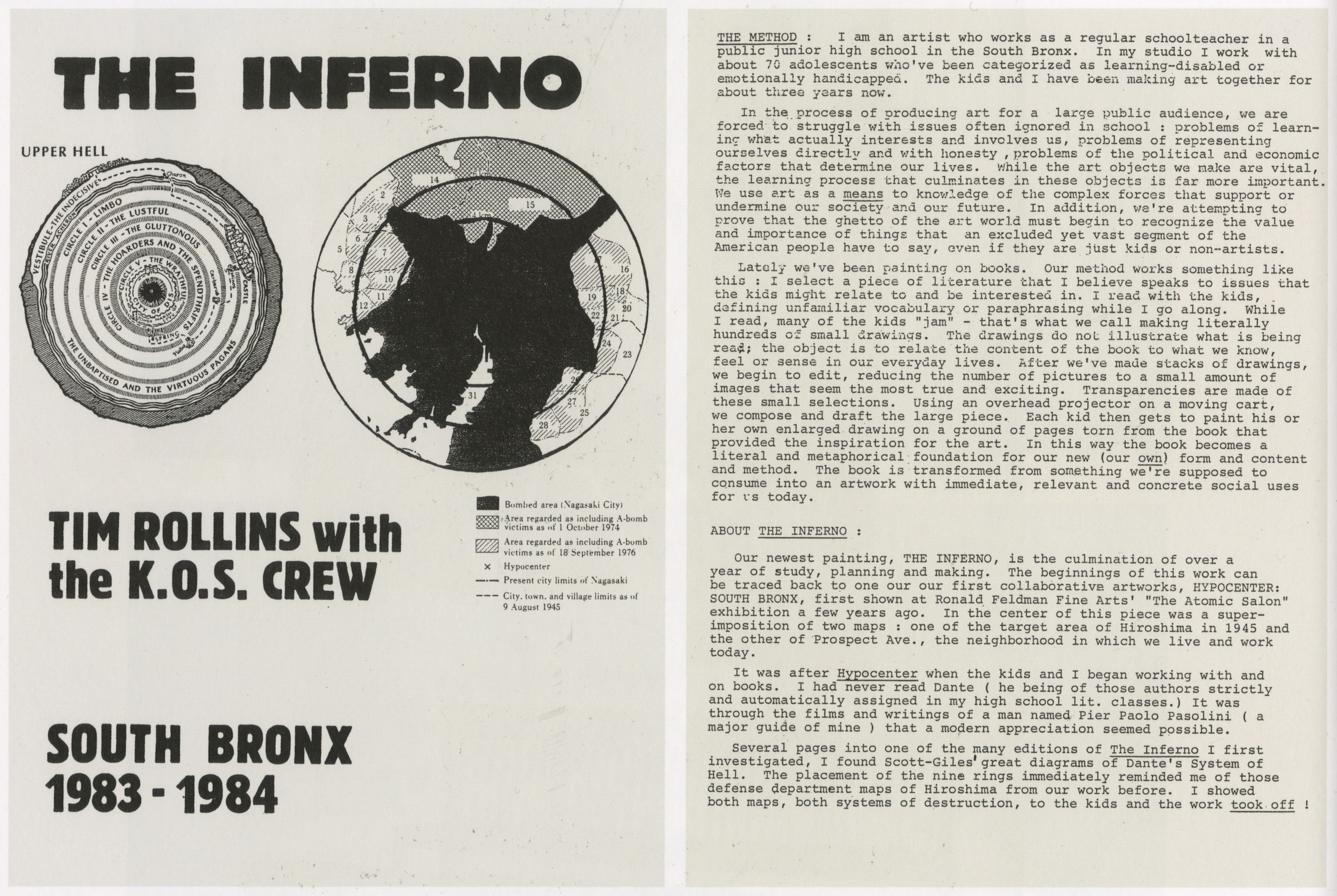

In 1981, Tim Rollins, artist and member of Group Material is appointed as a temporary per diem teacher at the intermediate School 52 in the South Bronx, where 95% of the population is defined making up the ‘minorities’ and 40% of the households are living on welfare. He works with teenagers who have been categorized as having learning disabilities. In 1984 he obtains a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts and open the Art and Knowledge Workshop, in an abandoned gymnasium two blocks from the school. A ‘self-selecting group of young artists’ meets him in this studio after school, every day from 3 p.m. to 7 p.m. Together, they do homework and make art (Romaines, 2009, p. 41). The group names itself ‘K.O.S.’, for ‘Kids of Survival’.

Rollins takes the radical decision of merging his art practice and his teaching. He decides that he will not train those ‘kids’ to become artists but rather that they will be artists together, right away: ‘A big problem with the traditional school is that it places the student in a constant state of preparation. […] I begin with a different premise. Instead of constantly training kids to “become” artists, why not take on the job of encouraging them to be artists now?’ (Berry, 2009, p. 12).

In a guide accompanying one of their first exhibitions (Rollins and the K.O.S. Crew, 1983–1984), he describes the basis of K.O.S. collective artistic work as follow:

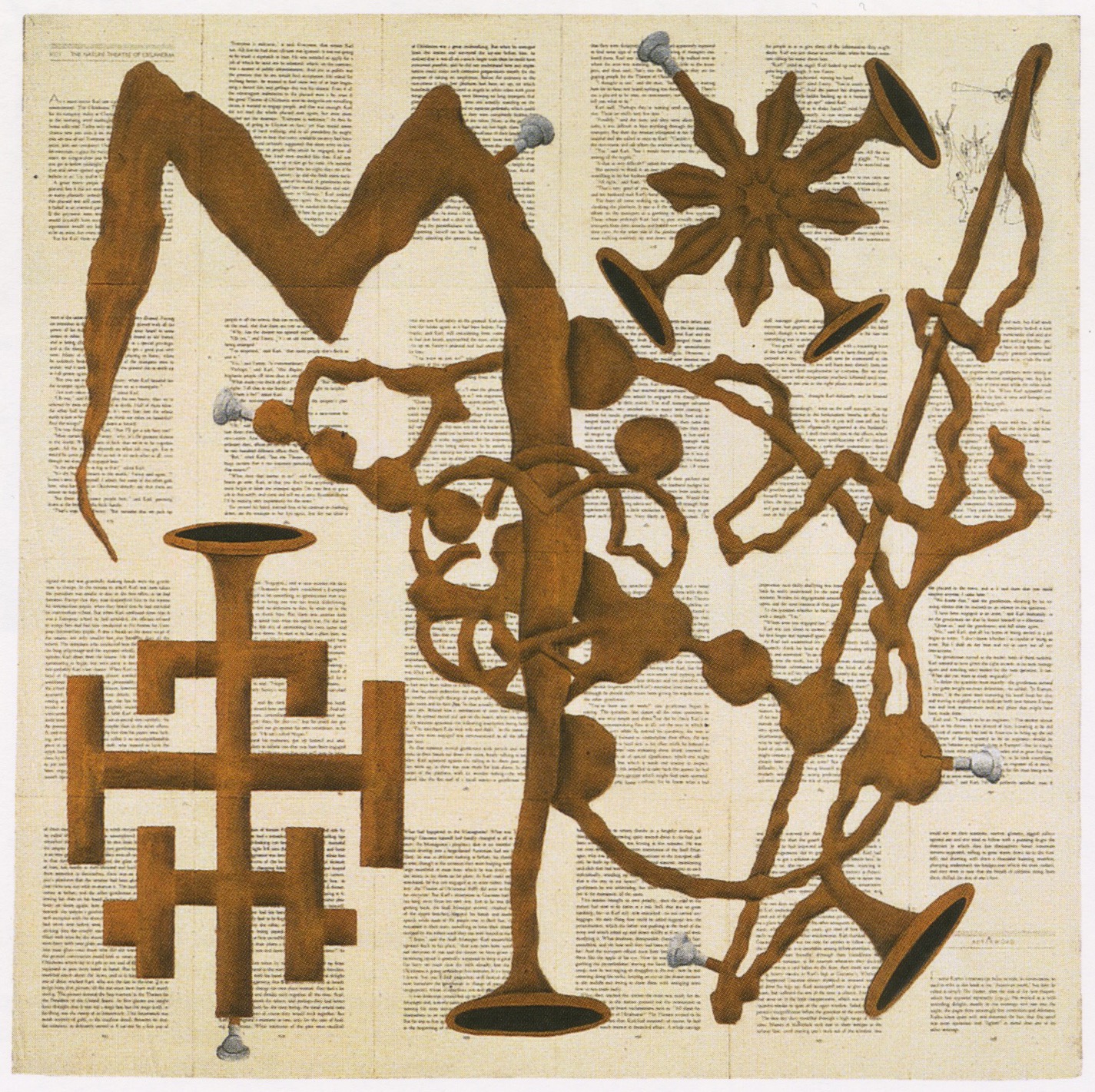

Lately we’ve been painting on books. Our method works something like this: I select a piece of literature that I believe speaks to issues that the kids might relate to and be interested in. I read with the kids, defining unfamiliar vocabulary or paraphrasing while I go along. While I read, many of the kids ‘jam’ – that’s what we call making literally hundreds of small drawings. The drawings do not illustrate what is being read; the object is to relate the content of the book to what we know, feel or sense in our everyday lives. […] Each kid then gets to paint his or her own enlarged drawing on a ground of pages torn from the book that provided the inspiration for the art. […] The book is transformed from something we’re supposed to consume into an artwork with immediate, relevant and concrete social uses for us today.

The guide also outlines their goals. First, they aim to produce art for a large public audience, which pushes them to deal with the issue of self-representation. Then they consider art as ‘a means to knowledge of the complex forces that support or undermine our society and our future’. Through their work, they want ‘to prove that the ghetto of the art world must begin to recognize the value and importance of things that an excluded yet vast segment of the American people have to say, even if they are just kids or non-artists’.

This initial statement is already tinged with Freire’s writing, tackling in a similar way the idea of acquiring knowledge in order to understand the society by which one is marginalized, and to imagine practical ways to transform the status quo. The will of the group to constantly go public and to present and discuss their work in the art world also echoes Freire’s (1970b, p. 181) idea of oppressed people becoming ‘actors who critically analyze reality […] and intervene as Subjects’.

In an interview given to James Romaine (2009), Rollins says, ‘As an educator, you do not give students anything; you can only be a resource. You take what the students already know and expand upon that, as opposed to dumping a truck load of new stuff on them that has no particular relevance to the students’ lives.’ Here one can see a very direct link to Freire’s critique of banking education, an education in which, for the Brazilian pedagogue (Freire, 1970b, p. 72), ‘the scope of action allowed to the students extends only as far as receiving, filing, and storing the deposits’.

And Rollins does indeed make direct reference to Freire when he talks about the main theories that helped him to conceptualize his approach (which, like Freire, he refuses to consider as a fixed method): 4

One of my most influential philosophical and spiritual mentors, the great Paulo Freire, consistently warns educators against inventing and replicating an ossified pedagogy or teaching system that does not organically respond to the ever changing educational needs and social context of people and communities. In the two decades of working with youth from distressed neighbourhoods worldwide, KOS and I are witnesses to the wisdom of Freire. A method is the madness of collaborative art making, a pattern in the process, has started to emerge.

He also writes: ‘I was moved to do it, but it comes from somewhere, from my love for the Reverend Martin Luther King and for Paulo Freire’ (Wei, 2014). Of further interest, we know that Freire’s writings were also discussed among K.O.S. members as part of their common bibliography. 5 a Workshop bibliography […] which K.O.S. distributed during its fairly frequent public appearances on panels. That bibliography also includes Paulo Freire’s A Pedagogy of The Oppressed’ (Wallace, 1989: 39–40).]

In an interview published in 1995 (Paley, 1995, pp. 45–46), Rollins gives a more specific insight about his reading of Freire, saying: ‘Also, the influence of Paolo [sic] Freire has been seminal to my ideas and work, especially that little monograph called “Cultural Action for Freedom” published by the Harvard Educational Review.’ 6

Even though there are no extant and specific writings by Rollins discussing how exactly he borrowed from Freire, reading Cultural Action for Freedom with Tim Rollins + K.O.S. work in mind definitely demonstrates many links between the two approaches.

First, as mentioned, Rollins’ approach involved producing collaborative art that would be made public. For him, only an acknowledgment of the ‘kids’ work’ from the official art world – or even the art market – could really ensure their recognition, by extension, transform the place of the workshop’s participants in society (on a symbolic level and, concretely. The sales were used to provide the material condition for the continuation of the workshop as well providing funds to pay for the participants’ higher education training that Rollins was aiming at for each and every K.O.S.) (Geller & Goldfine, 1996). Therefore, making their work and discourses public was intended as a way to provoke a larger change: ‘It’s simply not enough to impact the lives of only a dozen kids. If we have a fighting chance, we have the duty to make the project grow into a force that can have an effect on many others’ (Paley, 1995, p. 50). This movement toward finding one’s voice and making it audible, as part of a larger movement, is similarly described by Freire (1970a, p. 4) in the introduction to Cultural Action for Freedom: ‘We have only one desire: that our thinking may coincide historically with … all those who, whether they live in those cultures which are wholly silenced or in the silent sectors of cultures which prescribe their voice, are struggling to have a voice of their own.’

Rollins also repeatedly refers to the idea of ‘making history’. In the introduction to the documentary movie, Kids of Survival: The Art and Life of Tim Rollins + K.O.S. (Geller & Goldfine, 1996), he says: ‘You may think we are gonna be making a painting, but we are also gonna be making history. To dare to make history, to dare to make history when you are young, when you are working class or poor person, that’s a gutsy thing to do’. As peculiar as this statement might first sound in the context of addressing a small group of marginalized teenagers, it seems to be imbued with a similar idea to Freire’s (1970a, p. 4) – that conquering the use of words is ‘to assume direction of its own destiny’. And for Rollins (Romaines, 2009, p. 42), this approach will lead to a historical process, in the sense of ‘doing something or making something that extends or survives beyond the maker, beyond you, and has an impact on the world’.

In Cultural Action for Freedom, Freire also opposes a literacy system where illiterates are considered as ‘men marginal to society’, where they are considered as being oppressed by the system. He shows that in the first hypothesis, reality is mystified – kept opaque with alienating words and phrases – and that in the second one, the oppressed reinsert themselves into a reality that has been demythologized through a dialogue with the educators (Freire, 1970a, pp. 11–12). The process that Tim Rollins + K.O.S. develop addresses the same issue in two ways. First, the articulation between a continuous exchange between the ‘kids’ and Rollins (and between the teenagers themselves) about issues that they are interested in, and the collective production practice of ‘jamming’ described above, leads to a dialogical practice similar to the one defended by Freire. Second, by tearing apart literature classics and physically reappropriating them, their ‘opaque content’ is demythologized and becomes theirs. As the art historian Paley (1995, p. 40) writes: ‘By reclaiming the book from its previous set of historical interpretations and literary codifications, K.O.S. provides powerful resistance to many fixed cultural narratives, myths and representations.’ Nelson Savinon, a member of K.O.S., explains that the content of the books becomes ‘pertinent and concrete for [them] today’ (Paley, 1995, p. 41). This process makes it possible for the participants to escape what Rollins describes as ‘that terrible ghetto myth that reading is for white people, that books are the enemy’ (Paley, 1995, p. 43).

Freire (1970a, p. 14) makes a link between the notion of ‘surface structure’ (that he borrows from Chomsky) and the process of ‘codification’ that he develops and that involves the projection – as a slide – of a photograph or sketch representing ‘a real existent, or an existent constructed by the learners’, in order for them to ‘gain distance from the knowable object’. Rollins’ use of a projector and, above all, the way the books are distanced by dismantling them can be seen as part of a similar dynamic.

Finally, Rollins’ desire to engage with oppressed people (and he will put more and more energy in the K.O.S. project, ultimately leaving his collective Group Material to dedicate fully to it) (Ault, 2010, p. 131) can be seen as an example of what Freire presents as the engagement in social reality of intellectuals belonging to the elite. 7 According to him, such engagements are an effect of the historical transition produced by consciousness awaking.

Acting upon Reality: Ultra-red

Ultra-red is a sound-based collective with members – artists, activists and educators – in North America and Europe. It has been active since 1994, when it was founded in Los Angeles by two AIDS activists, and has developed projects intertwining art and political organization.

Between 2010 and 2014, the collective produced the content for nine workbooks presenting ‘protocols’ that are simultaneously a description of actions that happened, and the sharing of a series of ‘mutually agreed-upon terms for [future] action[s]’ 8 . In these booklets, histories of radical and popular education are presented as being of crucial importance to developing cultural actions.

One of the booklets, published in 2010, is entitled ‘Radical Education Workbook’ (Ultra-red, 2010b) and is intended as an answer to the absence (or marginalization) of radical education in the school curriculum, but also in social movements, in the context of the struggle against the austerity program laid out by the British coalition government (Ultra-red, 2010b, p. 4). The publication is meant as a tool to ‘inspire others to come forward with concepts, practices and histories of radical education in their communities’ (Ultra-red, 2010b, p. 5). Paulo Freire is presented as the key reference not only in terms of theoretical background but also in the way of thinking and organizing the booklet (Ultra-red, 2010b, p. 4):

Taking Paulo Freire’s suggestion of ‘reading the word and the world together’, each session – and subsequently each workbook entry – is divided into three parts: – Key concepts within radical education and their histories – Practices associated with the concept in classrooms and other less conventional educational settings – Reflection about the relevance of the concept to our struggles today.

Freire’s transformative approach is key here, but it should be noted that the idea is never to use an existing method but rather to rethink the pedagogue’s approach for today. Ultra-red (2010b, p. 58) summarizes its position, writing: ‘Freire’s work was very much a product of the particular historical circumstances in which he was teaching and writing, and his methods for literacy development were based on the particular linguistic features of Portuguese. Freire’s work has to be reinvented, rather than transposed, for different contexts.’

One section in the leaflet is entitled ‘Using the Pedagogies of the Oppressed’. It describes five pedagogical experiences – not directly connected to art practice – reengaging Freire’s approach and Augusto Boal’s ‘Theater of the Oppressed’.

The first of the two projects is a description – based on the book by John L. Hammond, Fighting to Learn: Popular Education and Guerrilla War in El Salvador – of the role that popular education played in the Liberation struggles in the 1970s and 1980s. The text shows how the literacy approach used was built on Freire’s method (selecting multi-vowel words that served both to learn other words with similar syllables and to discuss the importance of this word in the learners’ lives). Contrary to what Freire was recommending, literacy in that context took place in the midst of revolutionary struggle, rather than in a pre-Revolutionary moment.

The second project is placed under the heading of a Freire’s quotation about the political dimension of pedagogy, ‘education is politics […] The teacher works in favour of something and against something’ (Ultra-red, 2010b, p. 57) and presents an experiment led in English for Speakers of Other Languages classes. This positions itself against the idea ‘that […] teaching is not political, that it can be neutral’, an idea that is prevalent, and ‘re-enforced by many teacher-training programmes’ (Ultra-red, 2010b, p. 58). The text presents an approach beginning with a long (days, weeks or even months long) listening time as trust is built among the group. Culminating in a discussion around an issue arising during the first phase, the group then work collectively on visual representations of that issue (following Freire’s idea of ‘codification’). Finally, collaboration develops into action that tries to produce a change in society (for example organizing a demonstration or rewriting documents to make them more accessible to non-native English speakers). Through this sequence, the traditional roles of the pedagogical process are rethought and the educator becomes a facilitator rather than a ‘teacher’.

In another workbook, named ‘Re:Assembly’, Ultra-red focuses on a four-year long project developed in London, in collaboration with the St Marylebone CE school, starting in 2009. The project involved 150 pupils, several teachers, staff members and artists. Through many exchanges, various works were produced (and presented in an exhibition in 2013, in the school and at St Marylebone Parish Church), among which were:

- Hymnal, consisting of a series of songs, written from notes taken during discussions, walks and listening, realized by the students around the question ‘What is the sound of citizenship?’, embedded into a fabric in the church building.

- Songs for Edgware Road, a selection of songs from the Hymnal, performed by five students (who took part in a ‘summer work’ with the choreographer Gill Clarke), presented on a life-size video.

- A ‘Possible conversations’ video, presenting statements delivered by teachers (art teachers defending the art curriculum), students (students delegates) and local activists (migrant and gays & lesbians rights activists in particular), around the question ‘What do you hear in the city that informs the next step for the constituency of which you are a part?’ The statements are delivered individually but edited in facing pairs, to appear as conversations.

- Songs for getting through, a collection of plaster tiles inscribed with a selection of lines from songs that helps students ‘to get through the day’.

- Embroidered pieces of fabric, entitled Lessons, which are statements drawn from conversations with art teachers.

In those different phases – where Ultra-red’s call to reinvent Freire is embodied in the way issues such as women’s conditions or sexual minorities’ rights (which were not directly addressed by Freire) are tackled – the dynamic between listening to the existing situation and plotting possible transformation through a dialogical pedagogy is developed. In yet another booklet, ‘Practice Sessions Workbook’, Ultra-red (2014a, Workbook #9, p. 26) summarizes Freire’s education as follows, echoing their approach in ‘Re:Assembly’: ‘people start from their lived experience. Coming together in a group, they abstract, recount, discuss those experiences together. In the process of reflecting they then analyze their stories in order to understand the world as socially produced and, therefore, changeable. The dialectical relation between subjective and objective reminds us that by critically analyzing and acting upon the objective world we also transform subjectivity.’

If Ultra-red sees this work as a way to transform the existing situation, its members are conscious that this process cannot be limited to a single project. In its introductory text (as in the exhibition guide), it refers directly to Freire to call for further action (a call embodied, for example, in the ‘Protocols for Lessons’ proposed in the workbook (Ultra-red, 2014a, Workbook #9, p. 26)):

The investigation of citizenship is by no means over. While Re:Assembly represents an outcome of work together, it is offered as a starting point for the next phase of the investigation. It is to be considered not only as a response to the question, ‘What is the sound of citizenship?’ It is also an invitation for others to come together and take up the question within the context of this city. This is a process described by Paulo Freire, the Brazilian popular educator, as, ‘people’s thinking about reality and people’s action upon reality’.

Generating New Images of Brazil: Jonathas De Andrade.

A third example of reengagement of Freire’s thinking today (almost an update in this case, given the literal nature of the borrowing) is to be found in Educação para Adultos (Education for Adults) by the artist Jonathas De Andrade 9 . His project was presented at the 2010 Bienal de São Paulo, as a series of sixty small, framed, posters each composed of a word and an image illustrating that word.

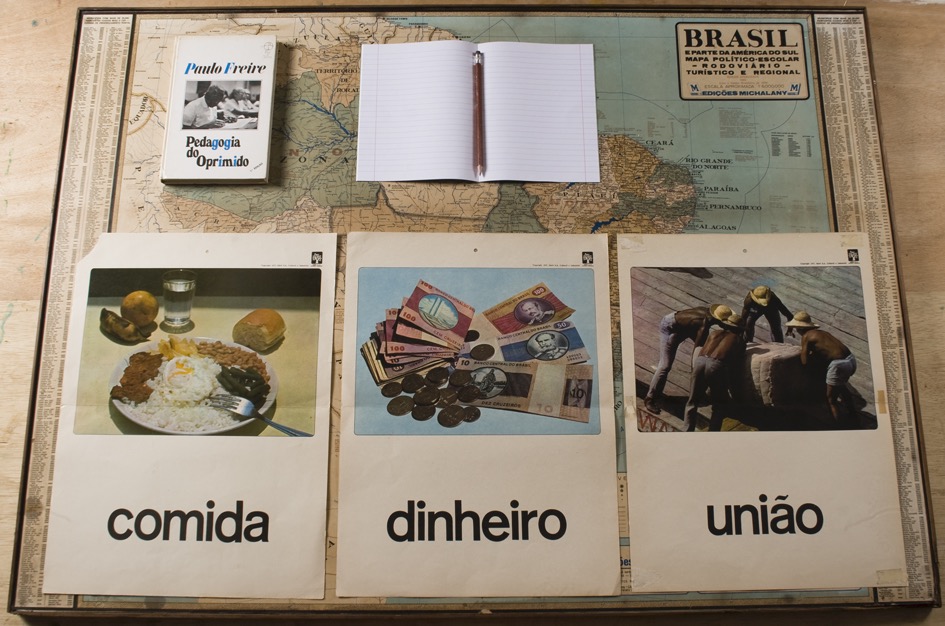

The viewer familiar with the pedagogical visual material developed for the ‘Freire sistema’ (see above) would immediately recognize the reference. And indeed, De Andrade – who studied in Recife, like Freire fifty years before him – developed this work after finding posters directly inspired by Freire’s pedagogy.

He tells this anecdote: at his parents’ place, he finds a set of twenty posters that his mother used in her work as a teacher in a Brazilian public school in the 1970s. Just like the prints in De Andrade installation, each poster displays a common word (for example comida (food), dinheiro (money) or uniao (union)) along with a picture illustrating the word. He seeks information about the material and learns that it was a pedagogical material inspired by the Freirean approach, and was sold by street vendors.

He then decides to take those posters – designed as a literacy tool – as a starting point to initiate an exchange with illiterate people in Brazil. Through professional organizations, he meets six washerwomen and seamstresses, with whom he will work every day for one month. De Andrade (2018) does not explain extensively how each meeting is organized but, rather, stresses that he feels ill at ease beginning a literacy process without really knowing the tools he is using and, above all, in introducing a method ‘without actually knowing how obtainable that political awareness is, or to what extent it truly is an exercise in liberty’.

Nevertheless, he sees in Freire’s approach an openness, the potential for being useful – even without having any previous pedagogical experience – recognizing the political existence of the other.

The daily meetings – through what De Andrade (2018) calls a ‘delicate negotiation’ that involves ‘inviting people to be social actors in a representation that is unfavorable to them’ and that makes him face his ‘own ethical immaturity’ lead to the production of new posters. Thus, if he introduces only the existing posters at the beginning of the process, he produces, after each day’s conversation, new posters around the topics discussed, posters that he adds one after the other to the collection, through what he calls a ‘educational-artistic mechanism’.

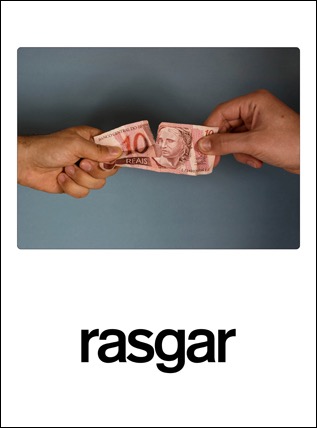

At the end, he has accumulated a collection of 60 posters, mixing previously existing ones and new ones. The collection is presented without any indication about what constitutes the historical material and which are the newly produced images. A harsh portrait of contemporary Brazil transpires – with words such as faca [knife], fogo [fire], riqueza [richness] or rasgar [tear apart].

In the sense of Freire’s generative themes, everything produced by the artist comes from the dialogue between himself and the participants and De Andrade (2018) writes: ‘Critical perception cannot be imposed, and perhaps the horizontality is that everything that comes up is what already exists in life experience, both theirs and mine.’

Toward The Next Reinventions

A key feature of Paulo Freire’s practical approach to literacy was the use of visual material. Images and paintings were meant as pedagogical tools to facilitate both literacy and the conscientization processes, to help learning the word and learning the world.

He also found in the classical figure of the artist a metaphor for the teacher – someone forming individuals and performing in the classroom.

Paradoxically, it is most certainly not the bridges between art and pedagogy he proposed that led him to become a key figure for many contemporary artists. In reading Tim Rollins, Ultra-red or De Andrade mentioning Freire’s approach to pedagogy – and looking into the projects that those artists developed – it seems rather that they found in Freire’s thinking some keys to answer a need to develop art practices that would be more dialogical, transformative and politically engaged.

This call for a dialogical approach to art – which had already appeared in the 1980s, as mentioned above – was the subject of renewed interest in the second part of the 2000s, around what has been described by the art historian Irit Rogoff (2008) as the ‘Educational Turn in curating’. At a moment of standardization of higher education on a European scale (through the ‘Bologna Process’) – which was consolidating an economic model based on commodified knowledge, and provoked many students protests – several curators and artists became more interested in the topic of pedagogy. And in the debates opened by those cultural workers, Freire was one of the figures repeatedly quoted by those who wanted to defend a political and critical approach to pedagogy against the market-oriented model. In 2007, in Amsterdam, during the International Workshop on Alternatives in Education (Pedagogical Faultlines, 2018), a talk called ‘Paulo Freire meets Tactical Media’ discussed ‘ways to explore the possibilities of interactivity amongst people as a new way to produce knowledge and culture’. In 2008 in Ljubljana, the collective Radical Education (Gregorcic, Piskur, Potrc & Vilensky, 2007) (participating with Chto Delat among others) developed ‘an open platform of knowledge production, exchange and dissemination, based on the concept of ‘education for critical consciousness’ as proposed by Paulo Freire’. In 2010 in a publication around one of the most representative (yet cancelled) projects of the ‘Educational Turn in curating', the Manifesta 6 School, Freire was called upon to consider an education that empowered and worked toward an ‘ongoing development of critical consciousness’ (ElDahab, Vidokle & Waldvogel, 2006). In those debates around the shift towards a market-oriented education, Freire’s ideas, like the critique of banking education, appeared quite naturally as a key reference, giving the pedagogue a renewed topicality.

Because Freire’s words so directly echoed a new and emerging kind of art practice, some art historians and critics saw in his texts – in the 1990s and still today – a way to define the dialogical practices of artists who ‘question the one-way communication between artist and audience’ (Finkelpearl, 2000, p. 283) and who develop what might be seen as a Freireian approach to art: a problem-posing art. The fact that Freire’s works could be so widely reengaged with in different times, contexts and in another discipline shows the real openness of his thinking, and one must remember that the pedagogue insisted on the fact that he needed to be not celebrated but that his writing should instead ‘be improved and reinvented by his readers’. 10

Fifteen years after the beginning of ‘The Educational Turn’ in curating – during which, as some cultural workers involved in gallery education have mentioned, 11 day-to-day education practice developed by critical educators has been too often neutralized by the discourses and forms developed by curators around this recent ‘educational trend’ – one can observe that a social elitism still predominates in the art institutions.

Freire’s approach has been identified by many educators as relevant to develop alternatives to the neo-liberal model of knowledge economy. Bruno della Chiesa (Harvard Graduate School of Education (2013), for example, notes that, ‘Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ is […] more relevant now than it ever was’ and Henry Giroux (Steinberg (2021) says:

Paulo’s work to me, is more important today than it actually was when he produced it. Because I think that the implications it has now for […] addressing the authoritarian forces that are at work and that are dismantling any notion of critical and public education [and that] are more intense than anything we have seen before. And if we don’t have a language, to understand that and to engage it, then I think we are in trouble.

Similarly, in order to work toward making art museums and centers more democratic, Freire’s writings can be a key resource because they provide the words and tools both to analyze the way these institutions currently include/exclude and to develop alternative approaches. His work is also intrinsically meant to be reinvented and can therefore be integrated today in critical gallery education projects or in socially engaged art practices.

References

Allen, F. (2008). Situating Gallery Education. In Tate Encounters, 2. http://www2.tate.org.uk/tate-encounters/edition-2/papers.shtm

Apffel-Marglin, F., & Bowers, C.A. (2004). Re-Thinking Freire: Globalization and the Environmental Crisis. Routledge.

Ault, J. (Ed.) (2010). Show and Tell: A Chronical of Group Material. Four Corners Books.

Bass, C., & Sholette, G. (Eds.) (2018). Art as Social Action. An introduction to the Principles and Practices of Teaching Social Practice Art. Allworth Press.

Berry, I. (Ed.) (2009). Tim Rollins and K.O.S.: A History. The MIT Press.

Bishop, C. (2012). Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. Verso.

Bishop, C. (2006). The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents. Artforum magazine, 44(6), 178–183.

Cockcroft, E., Cockcroft, J., & Weber, J. P. (Eds.) (1977). Toward a People's Art: The Contemporary Mural Movement. Dutton.

Creative Time (2021). Creative Time Summit. http://creativetime.org/summit/

De Andrade, J. (n.d.). Educação para adultos. http://cargocollective.com/jonathasdeandrade-eng/education-for-adults

Durham, J. (2006). Popocatépetl and its Environs. In Quauhnuahuac – Die Gerade ist eine Utopie. Kunsthalle Basel.

ElDahab, M. A., Vidokle, A., & Waldvogel, F. (2006). Notes for an Art School. Int. Foundation Manifesta.

Fávero, O. (2012). As fichas de cultura do Sistema de Alfabetização, Paulo Freire: um ‘Ovo de Colombo’. Linhas Críticas, 18(37), 65–483.

Finkelpearl, T. (2000). Paulo Freire: Discussing Dialogue [Interview]. In T. Finkelpearl (Ed.), Dialogues in Public Art (pp. 276–293). MIT Press.

Freire, P. (1978). As Educators we are Politicians and Also Artists [interview]. In B.L. Hall, & J.R. Kidd (Eds.), Adult Learning: A Design for Action. A Comprehensive International Survey (pp. 271–281). Pergamon Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Cultural Action for Freedom. Harvard Educational Review.

Freire, P. (1994). Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Continuum.

Freire, P. (1998). Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach. Westview Press.

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the Oppressed (M. Bergman Ramos, Trans.). Continuum. (Original work published 1974).

Freire, P., & Shor, I. (1987). A Pedagogy for Liberation: Dialogues on Transforming Education. Bergin & Garvey.

Gadotti, M. (Ed.) (2014). As fichas de cultura do Sistema de Alfabetização, Paulo Freire: um ‘Ovo de Colombo’. Instituto Paulo Freire.

Geller, D., & Goldfine, D. (Directors). (1996). Kids of Survival: The Art and Life of Tim Rollins + K.O.S. [Film]. CustomFlix.

Gregorcic, M., Piskur, B., Potrc, M., & Vilensky, D. (2007). A Conversation on Education as a Radical Social (and Aesthetic) Practice. Maska, 22 (103/104), 73–79.

Harvard Graduate School of Education. (2013, May 1). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Ll6M0cXV54

Helguera, P. (2011). Education for Socially Engaged Art. Jorge Pinto Books.

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to Transgress. Education as the Practice of Freedom. Routledge.

Institut d’action culturelle (IDAC) (Ed.) (1973). Conscientisation and Liberation, a Conversation with Paulo Freire. Document IDAC, 1.

Institut d’action culturelle (IDAC) (Ed.) (1976). Guinée-Bissau, Réinventer l’éducation. Document IDAC, 11/12.

Kester, G. (1999). The Art of Listening (and of Being Heard): Jay Koh's Discursive Networks. The Third Text, 13(47), 19–26.

Mörsch, C. (2011). Alliances for Unlearning: On the Possibility of Future Collaborations Between Gallery Education and Institutions of Critique. Afterall, 26(1), 4–13.

Open engagement. (2021). Open engagement. http://openengagement.info

Paley, N. (1995). Finding Art’s Place. Experiments in Contemporary Education and Culture. Routledge.

Paulo Freire. Der Lehrer ist Politiker und Künstler. Neue Texte zu Befreiender Bildungsarbeit (1981). Rowohlt.

Pedagogical Faultlines. (2021). International Workshop in Alternatives in Education. https://waag.org/sites/waag/files/Publicaties/programme.pdf

Pereira, I. (2018). Paulo Freire. Pédagogue des opprimé·e·s. Libertalia.

Rollins, T. (with the ‘K.O.S. Crew’). (1983–84). Guide to The Inferno (After Dante Alighieri) [Leaflet]. Fashion Moda Archives, Fales Library and Special Collections, Elmer Holmes Bobst Library, New York University.

Romaines, J. (2009). Making History. In Tim Rollins and K.O.S. A History (pp. 41-49). The Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College.

Rogoff, I. (2008). Turning. e-Flux Journal, #0. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/00/68470/turning/

Santiago, L. (2015, March 20). Chega de Doutrinação Marxista: Basta de Paulo Freire. Plano Critico, Fora de Plano, 14. http://www.planocritico.com/fora-de-plano-14-chega-de-doutrinacao-marxista-basta-de-paulo-freire/

Steinberg, S. (2012). Paulo Freire Documentary. Seeing Through Paulo’s Glasses: Political Clarity, Courage and Humility. Montreal: The Freire Project. https://freireproject.com

Sternfeld, N. (2010). Unglamorous Tasks: What Can Education Learn from its Political Traditions? e-Flux Journal, 14. http://www.e-flux.com/journal/unglamorous-tasks-what-can-education-learn-from-its-political-traditions

Terra, A. (1994). Antes da hora. In C. Fernandes, & A. Terra (Eds.), 40 horas de esperança. O método Paulo Freire: política e pedagogia na experiência de Angicos. Ática.

Ultra-red (2014). Ultra-red: Nine Workbooks 2010–2014. Koenig.

Ultra-red (2014). Radical Education Workbook. In Ultra Red, Ultra-Red: Nine Workbooks 2010–2014. Koenig.

Wallace, M. (1989). Tim Rollins + K.O.S.: The ‘Amerika’ Series’. In Amerika, Tim Rollins + K.O.S. (pp. 37-48). Dia Art Foundation.

Weber, J. (1979, November 11). [Letter to Paulo Freire]. World Council of Churches archives. http://archives.wcc-coe.org/Query/suchinfo.aspx

Wei, L. (2014). Tim Rollins and KOS’s Angel Abreu and Rick Savinon: interview. Studio International. http://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/tim-rollins-and-kos-s-angel-abreu-and-rick-savinon-interview

- Like Freire, Ceccon was a Brazilian exile in Geneva in the 1970s. He produced many cartoons illustrating Freire’s ideas, in particular in the publications of the Institute for Cultural Action (IDAC) that they founded with, among others, a group Brazilian exiles. The institute defined itself as ‘an international and interdisciplinary team whose interests and efforts converge toward the application of “conscientization” as a liberatory tool in the educational process and in the social transformation’ (Institut d’action culturelle, 1973: 17). For the Institute, Claudius Ceccon produced not only drawings to illustrate different printed material, but also tools that could be used in the pedagogical exchanges, like the 25-page comic he produced in dialogue with educators from Guinée-Bissau, after developing audio-visual material to facilitate their training (see Institut d’action culturelle (1976). ↩

- In Brazil, the reactionary movements were asking for the education system to shift away from Freire (see: Santiago, 2015) while in France, some present him as a remedy against a depoliticized education (see: Pereira, 2018). ↩

- The art historian Claire Bishop talks about ‘social turn’ to describe this evolution. Those practices, as Chloë Bass and Gregory Sholette (2018) note in the preface to Art as Social Action are currently moving from the margins to the center of the art world, gaining a new institutional legitimacy, sometimes in a form of contradiction with their activist roots. Large audience events such as the Creative Time Summit (Creative Time, 2018) and the Open Engagement conference (Open Engagement, 2018) are signs of this transformation. ↩

- In the 1984 ‘Guide to the INFERNO’ (Rollins and the K.O.S. Crew, 1983–1984), he nevertheless describes what he calls ‘the method’ but he presents it not as fixed rules but rather as a specific approach developed for one project in particular. ↩

- ‘[… ↩

- In an encounter with Rollins at the School of Visual Art New York where he was teaching, the authors were urged to read this book, which he considered as ‘much more inspiring than Pedagogy of the Oppressed’. ↩

- Even though Rollins is coming from a popular background, his training at the School of Visual Arts in New York and his inclusion in the official art world certainly makes him part of a certain ‘elite’. ↩

- ‘What did you hear?’, introduction card to the booklets, Ultra-red: Nine Workbooks 2010–2014 by Ultra-red (2014a). ↩

- To those three case studies many others could be added, for example in looking at the work (or the texts written about their works) of Invisible Pedagogies Collective, Radical Education Collective, Suzanne Lacy, Luis Camnitzer or Tania Bruguera. Jimmie Durham (2006) also writes: ‘Maria Thereza and I started our own school tram our house in San Anion. The students were boys from the other side of the barranca, where their families were illegal “squatters” in the fields. A woman aged about seventeen or eighteen who was a prostitute in the centre of Cuernavaca was also a student for a while, but she disappeared. Our idea was to apply the ideas of IlIich and Freire (who had been my neighbor in Geneva).’ ↩

- Freire (1998: 30–31). This is may be why even educators see flaws in his approach (which they describe as being sexist, western epistemology-based or as not taking the non-human environment into enough consideration) are still referring to him. See: Apffel-Marglin & Bowers (2004) or hooks (1994). ↩

- See in particular Nora Sternfeld’s (2010) text: ‘Unglamorous Tasks: What Can Education Learn from its Political Traditions?’ ↩