This text was first published as a “Learning Unit” of the Intertwining HiStories cluster of the Another Roadmap School.

Other Learning Units (some of them also around the work of Paulo Freire) written by other members of the network can be found here: https://www.another-roadmap.net/clusters/intertwining-histories/tools-for-education-intertwining-histories/learning-units-intertwining-histories/

ABSTRACT

This Learning Unit offers historical information about the ten years the pedagogue Paulo Freire (1921, Recife – 1997 São Paulo), his wife Elza and their children spent in Geneva in the 1970s. It also presents four experiments, realized by autonomous gallery educators, to reinvent and reengage Freire’s thinking in present-day Switzerland. Finally, it opens some ideas to translate those experimentations in other contexts.

The Reenagaging Freire Learning Unit is a first step to reinstate Paulo and Elza Freire in Geneva’s history of pedagogy, from which they are strikingly absent. It is also an attempt to imagine experimentations that interrogate the topicality of Freire today in Switzerland (as the gallery educators did in developing a feminist choir, a community garden, a construction workshop in a popular neighborhood or a long-term experiment around the future of asylum-seeker youth), imagining how concepts such as untested feasibilities, conscientização, codification or generativity could serve as tools to question the contemporary dominant models of arts education.

ADDRESSEES

The Learning Unit is addressed in particular to gallery educators willing to understand Freire’s approach to provide accurate tools to transform their own practice.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. An introduction to the Learning Unit

2. Vagabond of the Obvious. Paulo Freire in (and out of) Geneva

3. Reengagement experimentation – Introduction

Annex to the first part: Examples of Freire’s concepts to reinvent/reengage

-- PART 2 – SUB-LEARNING UNITS --

A) Toward a Feminist Conscientização

- A1) A more inclusive writing – naming women and acknowledging Elza Freire’s role

- A2) Re-invention/reegagement experiment: Feminist Choir

- A3) Ideas for possible translations

B) Thematic universes in a migration society

- B1) A word tree rooted in Freire’s approach

- B2) Re-invention/reegagement experiment: Community garden

- C1) Critical reading of the Swiss school system

- C2) Re-invention/reegagement experiment: We Tube

- C3) Ideas for possible translations

- D1) Transforming the future of children living illegally in Geneva

- D2) Re-invention/reegagement experiment: Zackig Zukunft zeigen

- D3) Ideas for possible translations

PART 1

1. INTRODUCING THE LEARNING UNIT Presence/absence

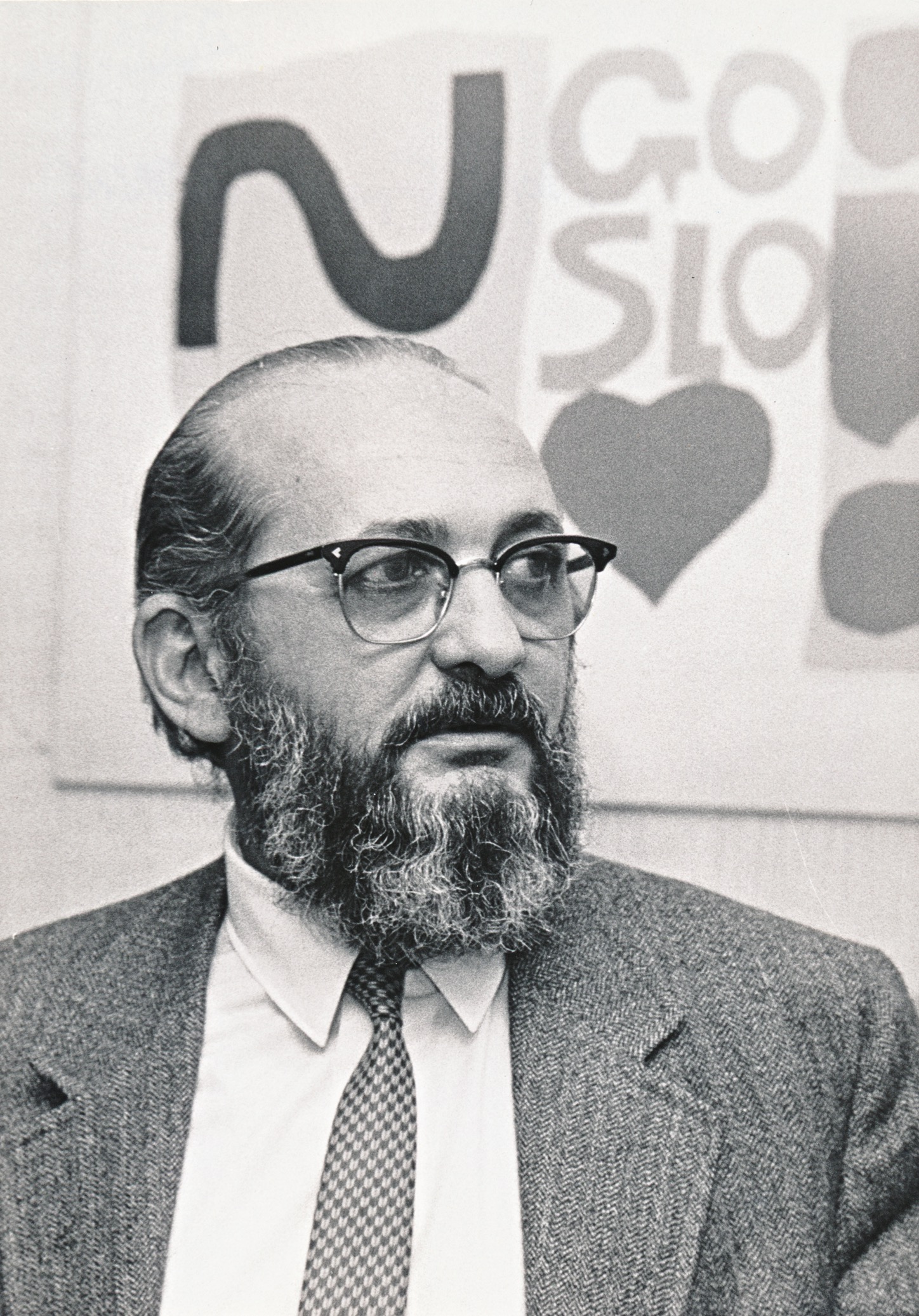

Paulo Freire (1921, Recife – 1997 São Paulo) is recognized as one of the most influential educationist on the 20th Century 1 . Since his seminal Pedagogy of the Oppressed (first published in English and Spanish in 1970), he wrote almost 20 other books, and dialogued with key figures in the field of critical pedagogy 2 . Until today, his work is widely discussed, in particular by academics, education practitioners and cultural workers 3 .

Freire’s work is also of great topicality. Henry Giroux says 4 :

Paulo’s work to me, is more important today than it actually was when he produced it. Because I think that the implications it has now for [...] addressing the authoritarian forces that are at work and that are dismantling any notion of critical and public education [and that] are more intense than anything we have seen before. And if we don’t have a language, to understand that and to engage it, then I think we are in trouble.

On the other hand, during the demonstrations against President Dilma Rousseff that occurred in several Brazilian cities in March 2015, signs displaying the slogan “Chega de doutriniçào Marxista. Basta de Paulo Freire” [Enough with Marxist doctrine: enough with Paulo Freire] could be seen, asking for a “depoliticized“ education. 5

Yet, this text will begin not in discussing his worldwide long-term presence but a peculiar absence. Being in exile since the 1964 military coup d’état in Brazil – and after fleeing to Bolivia, Chile and the USA – Freire lived in Geneva between 1970 and 1980 in Geneva, with his family. There, he worked for the Office of Education of the World Council of Churches (later: WCC) from where he travelled around the world and “became an international figure” 6 , “projected himself in the 20th Century History of education, as a citizen of the world”. 7 Despite those years being crucial for the construction and spreading of his ideas, little attention has been given to that period by researchers 8 . Moreover, Freire is strikingly absent of the academic 9 , media 10 and geographical spaces 11 in the capital of pedagogy that Geneva is.

This absence has to be thought in parallel with two facts. First, the fact that he was an exile in this city and that – as we will see later on – many of his most concrete actions in the city were linked to people in situation of migration that, he himself observed, were “hidden” 12 . Even in his professorial work at the Geneva University (where he would hold a seminar and from which he would received an honorary doctorate in Sciences of Education in 1979), he seemed to work mainly with non-Swiss students 13 (which certainly had to do with the fact that he was neither at ease with French 14 .] nor to a lower extent, with English 15 . Second, the fact that Freire is largely overlooked in the French-speaking world 16 .

Our research – to be presented in an article that will be published by the University of Geneva, along with a series about the Geneva history of pedagogy in the 20th Century 17 – aims at reinstating Freire in the history of Geneva. More generally, it aims at participating in the spreading Freire’s ideas in the French-speaking world.

Even most importantly – with a bigger sense of urgency – we are aiming at reengaging Freire in the present, inviting colleagues (from the art field in particular) and friends, to reinvent his thinking in order to plot alternatives to the dominant merchandised, content-oriented, managerial, accountable, professionally- oriented (a banking model of education as Freire would have named it 18 ).

Our Learning Unit is an invitation to join this movement.

Finally, a key dimension of our research is to reconsider the role that Paulo Freire’s wife , Elza Freire, played not only in a support of her husband’s work but also in the very conception of it. Elza was a primary school teacher for many years and her influence is attested by the numerous dedications and references made by Paulo Freire in books, interviews or letters, as we will see later. Elza herself produced manuscripts that were never published, but that were researched by Nima Spigolon 19 :

There is a need to do research on the figure of Elza, to look at her personal and professional trajectory in depth. [The] manuscripts produced by Elza, since they reveal the thought of the intellectual educator and her political-pedagogical practice, as well as her presence in the work (thought and praxis) of Paulo Freire.

Freire and us

Since we decided, 12 years ago, to make our artistic practices a collective one, we – as microsillons – have developed art projects in collaboration with people who don’t consider themselves as artists. As this practice is a dialogical one, we were immediately interested in critical pedagogies – for the way they change the traditional master-pupil relationship. Thus, Freire (that we discovered through reading bell hooks first) was one of our first common readings and became instrumental to our approach to art and gallery education.

We developed a kind of fascination for his writing and for the figure: a romantic symbol of struggle who offered us a political alternative to the scientific approach of pedagogy, more developed in Geneva and in the French speaking world. A character that is both far away (identified first to Brazil) and close (we felt a proximity way before we discovered, only many years after having read Pedagogy of the Oppressed for the first time, that he actually lived in the city where we founded our collective).

Through our research, we are trying to go beyond this fascination, understanding both that the critical approach that make his writings relevant is to be pursued and that he himself hated to be considered as “a guru”, constantly calling “to engage with [his] theoretical proposals, dialogically [and to] create possibilities, including the possibility that [he] can be reinvented [...]” 20 . A very revealing anecdote to that regard is that he refused in 1973 for a school to be named after him, arguing that “[...] it may be more helpful to search for a work of action rather than a personal name [...]” 21 .

Paradoxically, such a critical approach is made difficult by the fact that his thinking is non-dogmatic and calls for the critics instead of dismissing them. To this regard, bell hooks 22 writes:

This is why it is difficult for me to speak about sexism in Freire’s work; it is difficult to find a language that offers a way to frame critique and yet maintain the recognition of all that is valued and respected in the work [...] Freire’s sexism is indicated by the language in his early works, notwithstanding that there is so much that remains liberatory. There is no need to apologize for the sexism. Freire’s own model of critical pedagogy invites a critical interrogation of this flaw in the work. But critical interrogation is not the same as dismissal.

We approach our work with the idea that Freire needs to be reengaged, but through a critical re-invention.

Methodology

This research project is articulated in two synchronic parts:

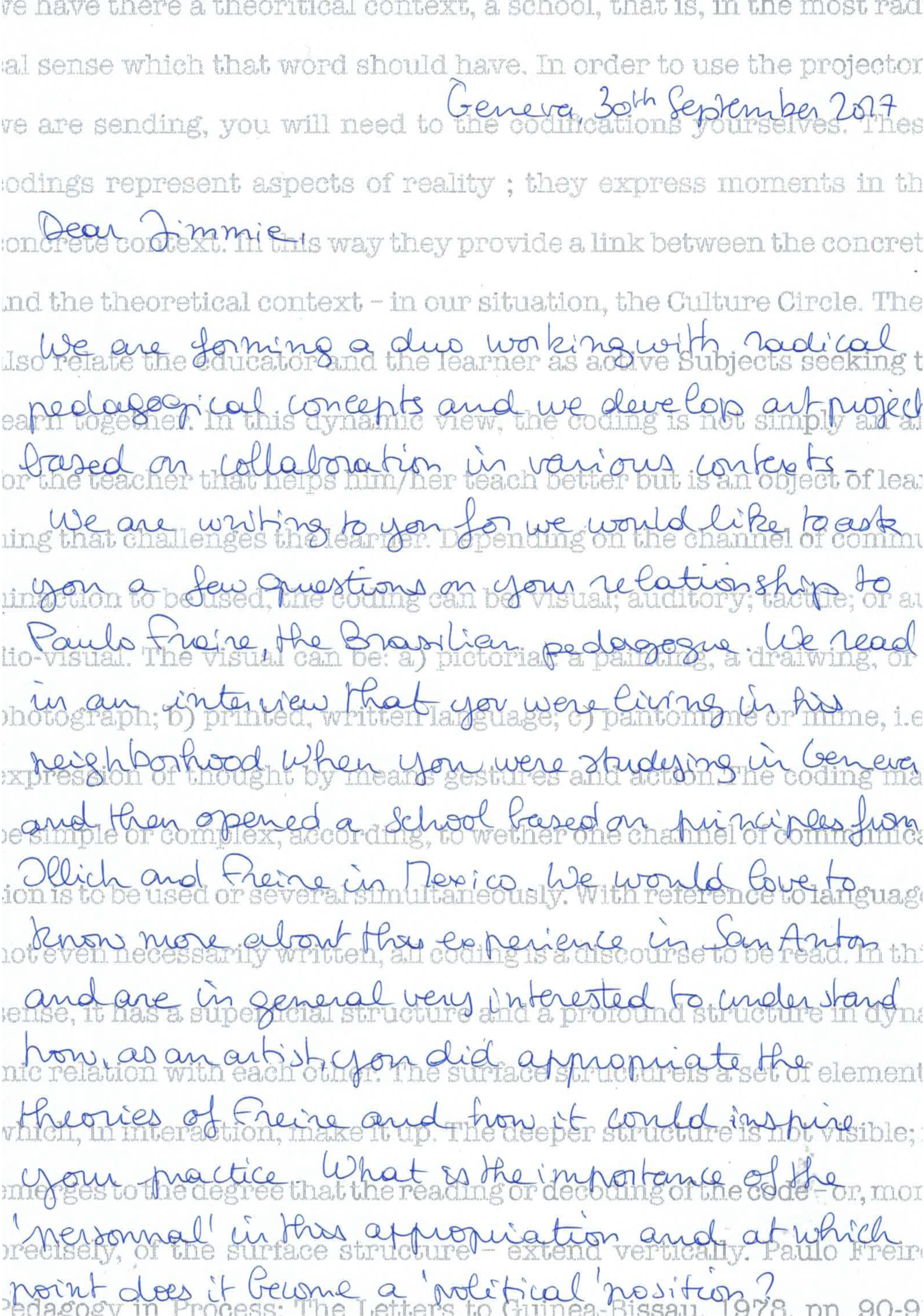

First, an historical investigation, based both on a work with the archives of World Council of Churches 23 (as well as with some other written sources 24 ) and on the construction of a network of people who knew Freire and are bringing their own perspectives to a polyphonic history writing 25 . To contact people to join this network, we wrote letters to them, in the line spacing of selected Freire’s texts.

Second, the re-invention and reengagement of Freire’s approach with a group of cultural workers in Geneva and abroad, in the spirit of a participatory action research (a type of research that was in part inspired by Freire’s text Creating alternative research methods. Learning to do it by doing it 26 )27 .

In the course of our work, we also open dialogical spaces to discuss our reflections with peers, often leaning on some material from the archives (that we completely digitalised to facilitate knowledge circulation).

This approach makes the construction of discourse more complex, less authoritarian and helps the development of other research from our initial findings. We have presented our research in rather classical conference or seminar contexts (Seminar “Actualité de la recherche”, HEAD – Genève and University of Geneva, Colloquium “Genève, une plateforme de l’internationalisme éducatif” at the University of Geneva in 2017; Seminar Aprendre a imaginar-se. Sobre pedagogies i emancipació, MACBA in 2017 ; Opening of the Creative Time Summit The Curriculum, Venice Biennale in 2015), we also did worked on more dialogical and artistic/performative approaches:

- For one semester in 2014, , we worked with a group of students in the CCC Research-Based Master Program and they developed a video project starting from a Freire’s text after we introduced his writings to them.

- In the 2015 Biennale des espaces indépendants de Genève, we organized a discussion around the notion of public, based on the comparison between a cartoon found in the WCC archives and a document produced by the Geneva Département de la culture.

- During the 2016 São Paulo Biennale, we proposed to the intertwining hi/stories cluster members a moment of exchange around a feijoada (that we learned to cook the day before with the help of Sofía Olascoaga (one of the Biennale curator and a member of the Intertwining HiStories of arts education network). This meal was both a reference to Freire in Geneva (see note 11) and to the notion of oppression (as the feijoada is traditionally a meal cooked by enslaved people with the rests left by their masters). It was served on table sets showing excerpts of documents found during the research. While serving the Feijoada, the cluster members were invited to each select one document in a series of copies of documents collected from the World Council of Churches. During the meal, each one presented the document she or he selected, explained the reason of her/his choice and found connections with her/his own research projects.

- In the Institut d’art contemporain in Villeurbanne in 2016, we organized an event/performance based on the listening of a collection of sound recordings of Freire (or around him), and on the discussion of several documents with a group of local art educators and teachers, in a convivial setting.

- In 2017 at the intertwining hi/stories of Arts Education Festival in Vienna, we organized a workshop around letter writing, working with a selection of letters from the WCC and writing new letters around the participants’ research topics.

- For the intertwining hi/stories of Arts Education symposium in Zürich, June 2018, we brought elements of Freire’s four experiments of reengagement of in Geneva (see below) to the participants and engaged in a critical discussion of them, particularly with the idea of inventing possible translations of those projects for new or different contexts.

- In Paris, in 2018, for the opening of the Institut bell hooks/Paulo Freire, we presented graphical work and sound recordings of Freire at the WCC that we digitalized and that were played several times over the course of the two-day conference.

2. VAGABOND OF THE OBVIOUS

Paulo Freire in (and out of) Geneva

After developing methods to overcome illiteracy in Brazil – since 1947 in the Nord-East and on a larger scale under the patronage of the federal government since 1962 – Freire is imprisoned following the 1964 coup. He flees to Bolivia and then Chile (where he writes Pedagogy of the Oppressed, works as a professor and becomes a consultant for the UNESCO). He is then a visiting professor at Harvard (1969-1970) and has the opportunity to observe the heart of the capitalist system, to “see the beast closer” 28 . Then, he lands in Geneva, where he accepted a position as special consultant in the newly founded Office of Education at the World Council of Churches.

Created after the Second World War, the World Council of Churches aims at unifying Christians from all around the world, regrouping most of the churches in the world with the notable exception of the Catholic Church. As a Christian instrument, based in the West, and in a so-called neutral country, it can be regarded as an agent in line with the missionary and colonial tendency to spread Christianity as a Universal Truth and to seek to help others qualified as being “in need” (development has been a key notion in the organization’s discourse (Kirkendale, 2010:92)). Even within the Christian world, the Council – which had always been interested in social issues (Kirkendale, 2010:92) – has been criticized for having been “too monolithic both in theological approach and in empirical analysis”, failing to “do justice to the diversity of situations faced by Christians, the different opinions they hold, and the variety of methods they employ in their social thinking” (Preston, 1994:12).

Beginning its activities in the context of the Cold War, and despite being largely financed by US money, the organization still avoided lining up with the “West“ against the Communist states (Preston, 1994:21), showing a strong will to represent churches in their largest possible diversity. This inclusive approach became even stronger at the end of the 1960s. Indeed, the Geneva conference in 1966 was remarkable in terms of the number of representatives from Africa, Asia and Latin America. They were plenty enough and vocal enough “so that the ‘Westerners’ could not dominate the proceedings” (25). The tone of the conference was radical and many heard the words “theology of revolution” or “conscientization” for the first time (Preston, 1994:25-26). It is in that particular context that Paolo Freire joined the organization and promoted the idea that the poor are agents rather than objects of their own development (Kirkendale, 2010:92).

He sees this position of working for an international organization as an opportunity not to lose contact with field work and, moreover, to be directly involved in the liberation process of former African colonies by having the opportunity and funding to travel around the world for the WCC 29 . Indeed he imagines himself playing a real political role through his actions and quoting Fanon writes in his WCC acceptance letter 30 .]:

You must know that I made a decision. My cause is the one of The Wretched of the Earth. You must know that I chose revolution.

And even after having lived in the US and in Switzerland for years, he considered himself, as “a man from the Third World and as an educator completely committed to the world [...]” 31 .

Freire lived in Geneva for a decade, but he did travel all around the world during that time. The council offered him “a worldwide chair” 32 and he labeled himself a “vagabond of the obvious” 33 , travelling around the world to “help people see there is no possibility of a neutral education [...]” (among his peers too, having to defend his position against many doubtful critics after he was hired 34 would defend banking education”. Some also think that “he has failed to come up with the correct answer”. About those critiques, see also Kirkendall (2010: 94-95).] he insisted on the importance of defending a non-neutral education) 35 .

Between 1970 and the end of 1974, he had already travelled outside of Switzerland 75 times, on five continents, mostly for a few days but sometimes for quite a long time.For example, he spent five weeks in Chile at the beginning of 1971, 40 days in the US in Spring 1972, and more than one month in Oceania in April-May 1974).

Again, his presence in Geneva is marked by an absence, this is evidenced by the fact that many of the letters from the archives are “not personally signed due to his absence” and the many invitations he turned down due to a full schedule.

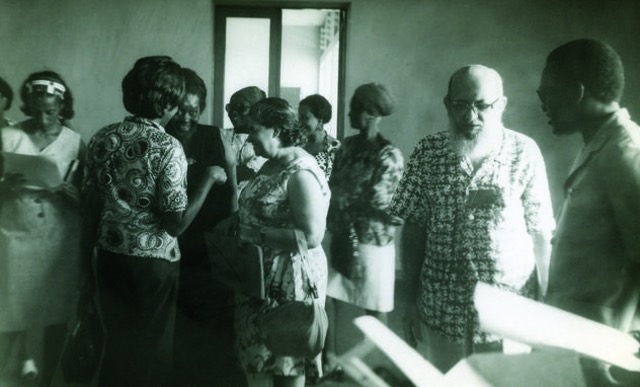

He is away giving talks, taking part in seminars, playing an advisory role as a consultant, meeting groups practicing educational or cultural action (sponsored by The Office of Education or not, coordinated by religious institutions or not), taking part in UNESCO meetings 36 , press conferences or radio shows. He is also meeting politicians (like the Portuguese Minister of Education in 1974, just after the Carnation Revolution).

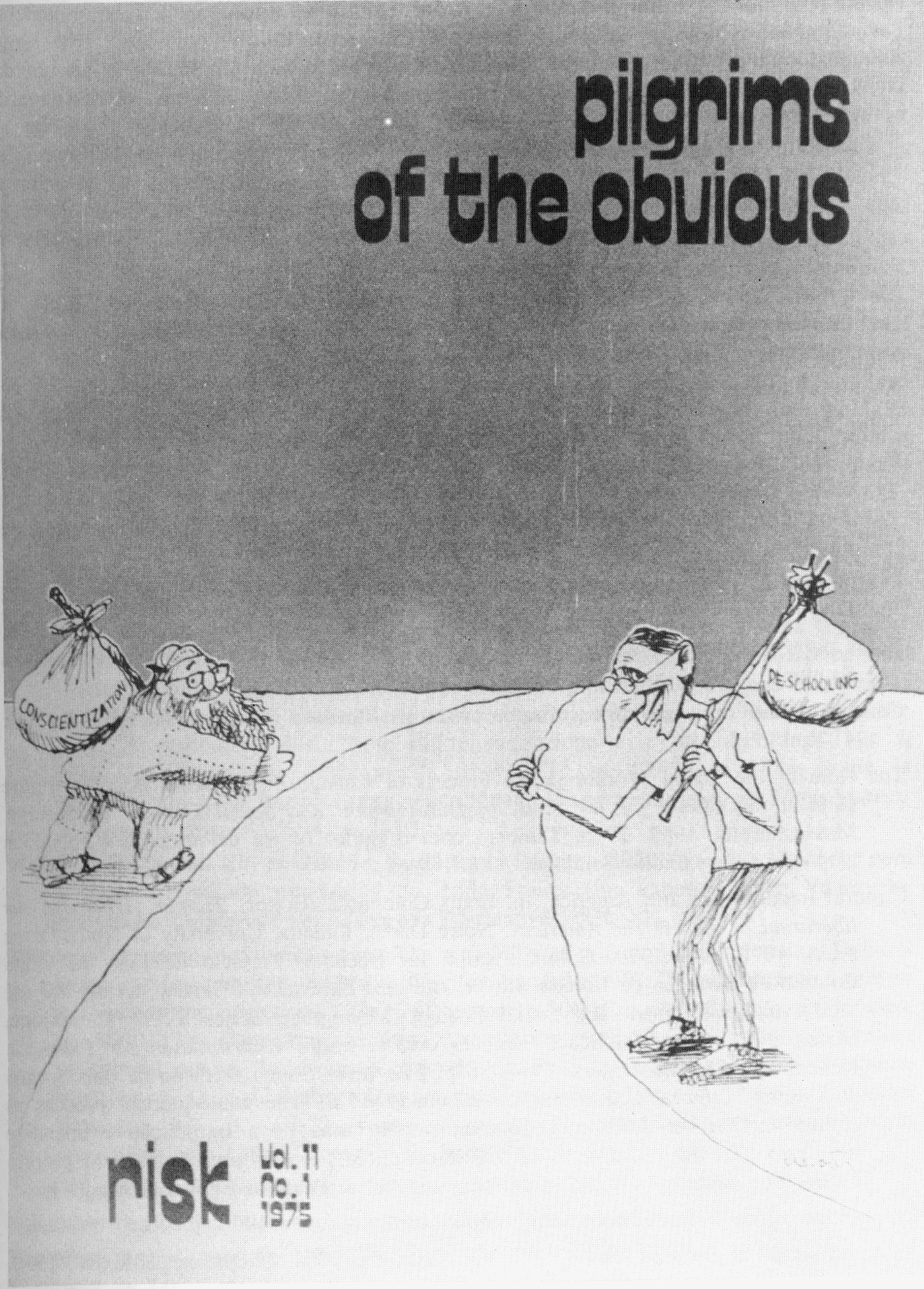

More seldom, the dynamic is reversed and the WCC is becoming a space to officially welcome key education thinkers of the time. Thus, after the first visit of Ivan Illich to the Council (in September 1970) and after Freire visited Illich in Cuernaveca, to give a two-week seminar at the CIDOC 37 , a seminar (named An invitation to conscientization and deschooling: a continuing conversation) bringing together Illich and Freire was organized by the World Council of Churches, on September 6 1974 38 .

If he already went through some doubts, it was during those first years (he writes in 1972 in a letter: “I learned a lot from both these trips, above all how difficult it really is to change a society”), he seems to experience a real crisis around 1975. He writes in October 1975: “I wish I could tell you that everything in the garden is rosy but unfortunately this year we have had a lot of problems at home. [...] Also my many trips and other commitments have greatly tired me, so as you can see 1975 has not been the best of years for the Freire family. Let’s hope 1976 will be better” 39 . He also writes: “My work is pilling up [...] I am beginning to wonder how I am going to get through the year” 40 . Consequently, he asks to be released from his engagements at the Institute for the Sciences of Education at the Geneva University for 1975 and 1976 41 .

Freire feels he is “existentially tired” 42 and is willing to do less, even considering staying in Geneva for a full year 43 . Funnily enough, it is in that same year that he met Evarist Bartolo (currently Malta Minister for Education) in Sicily, Bartolo who recalls “him always humming to himself the song ‘To dream the impossible dream’ [from the Broadway musical Man of La Mancha] 44 ”. At that time Freire might have feel somewhat like Don Quichotte, fighting in vacuo.

On the institutional level, Will Kennedy, head of WCC Office of Education, remarks, with others, that if Freire’s ideas are spread out, they still have a relatively small impact. He thinks that the office needs a sharper focus 45 . He decides to quit and is not replaced before 1977.

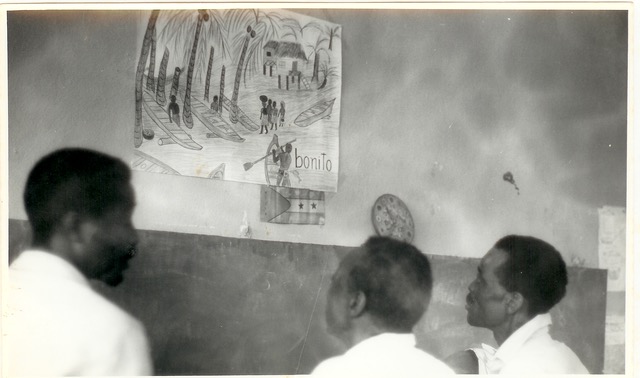

But around the same time, this “sharper focus” is found and Freire is soon involved mainly in the kind of work that he was looking for when he decided to join the Council. Indeed, after receiving invitations by different newly formed governments in Africa, he works closely with them to think of literacy actions in former Portuguese colonies.

In some cases, those invitations came through the Institute for Cultural Action (IDAC) an organization that he founded in 1971 with other Brazilian exiles (soon joined by Swiss intellectuals). In their first publication 46 , the IDAC members claim to work “toward the application of conscientization as a revolutionary factor in education and social change”. In the second issue 47 , they define four main fields of action: helping the “Third-World” in education and development; developing the contents and the methods for a political pedagogy, working for women liberation; inventing new forms of political action in highly industrialised countries 48 . And, coming back to the IDAC in 1980, some of its members list three key projects that were very close to the initial program: popular education with Italian workers in the frame of a union struggle (1972-74); experiences with the feminist movement in Switzerland (since 1973); experiences in school restructuration, literacy work and adult education in the frame of the liberation movements in Guinea- Bissau (1976-79).

In the beginning, the institute worked mainly through holding workshops in the US and in working with Italian workers. It had trouble to sustain itself and therefore, had to turn down several invitations 49 . But its situation improved and in 1975 a collaboration proposal by the Guinea-Bissau government was received. Gadotti 50 makes the hypothesis that the autonomy of the IDAC made it easier for Freire to get the WCC’s authorization to get involved in liberatory processes, as the question of validity of such involvements was a point of tension within the Council.

In Africa, Freire worked on a longer term, in connection with people he admired (like Amílcar Cabral) and he had the chance to travel and work more with his wife Elza (see A1), all of which helped him to find a renewed energy. In a 1977 activity report, he writes “I cannot hide my satisfaction at being able, through the Office of Education, to participate even minimally in the extraordinary effort that these societies are developing to reinvent themselves” 51 . In those countries, he is also happy that he “had met Brazil in Africa [and talked] about very concrete things, tastes, fruits, smells” 52 .

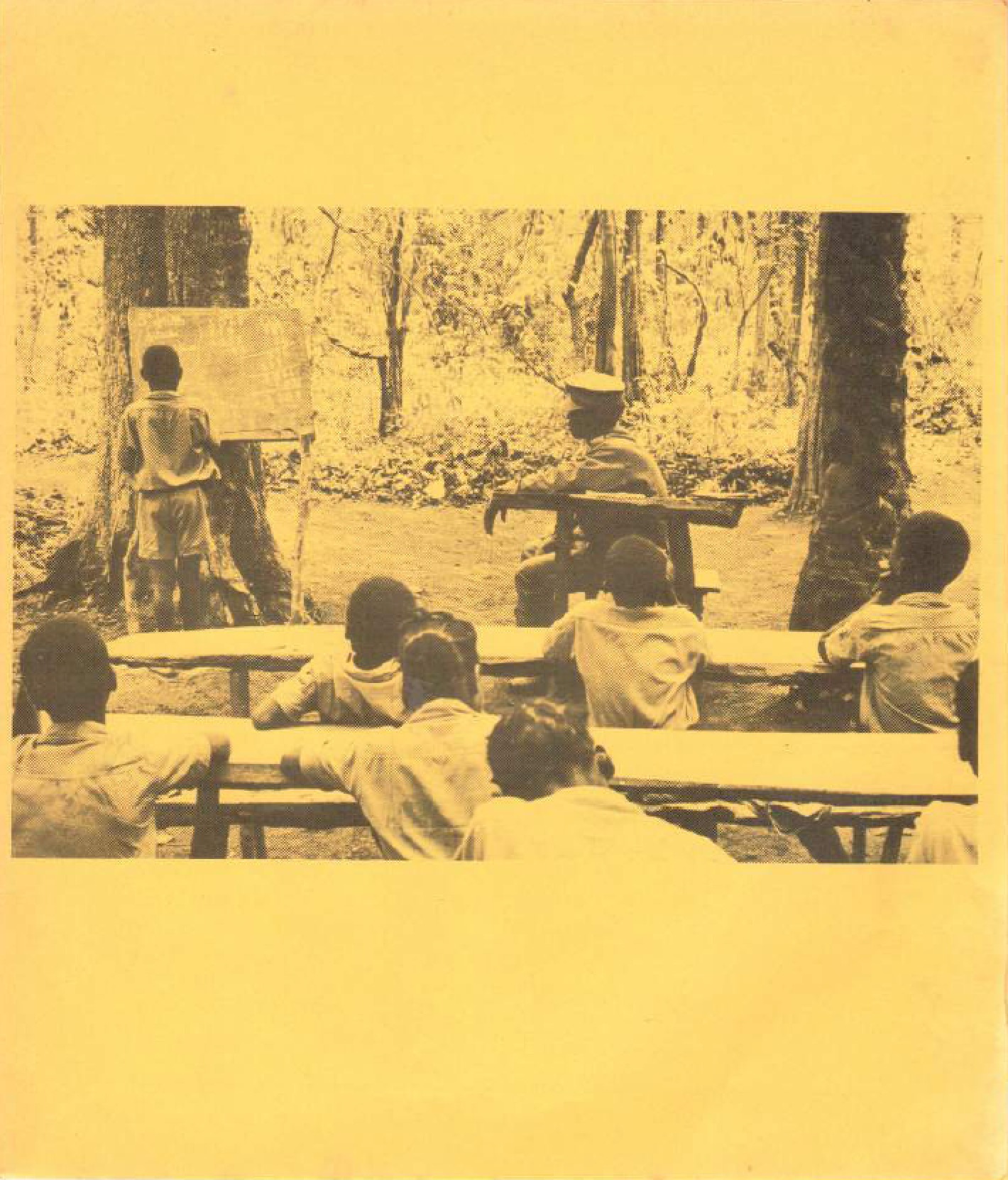

Between September 1975 and April 1980, he travelled to Guinée-Bissau 10 times, six times to São Tomé & Principe, five times to Angola and three times to Cape Verde. If the exchanges he had directly influenced the pedagogical approaches of those governments, he would be directly involved in the development of literacy programs (in particular in the training of cultural animators) only in Guinée-Bissau and in São Tomé & Principe, in both case with the IDAC. He insisted that he wouldn’t apply any model of pre-existing educational programs in those countries, but that he would start again from an observation of the context, as he did in Brazil. In a 1977 letter, he writes :

[...] I am very happy to be able to work in these educational programs. It means a lot to me to re-learn and to work with people who are trying to become themselves.

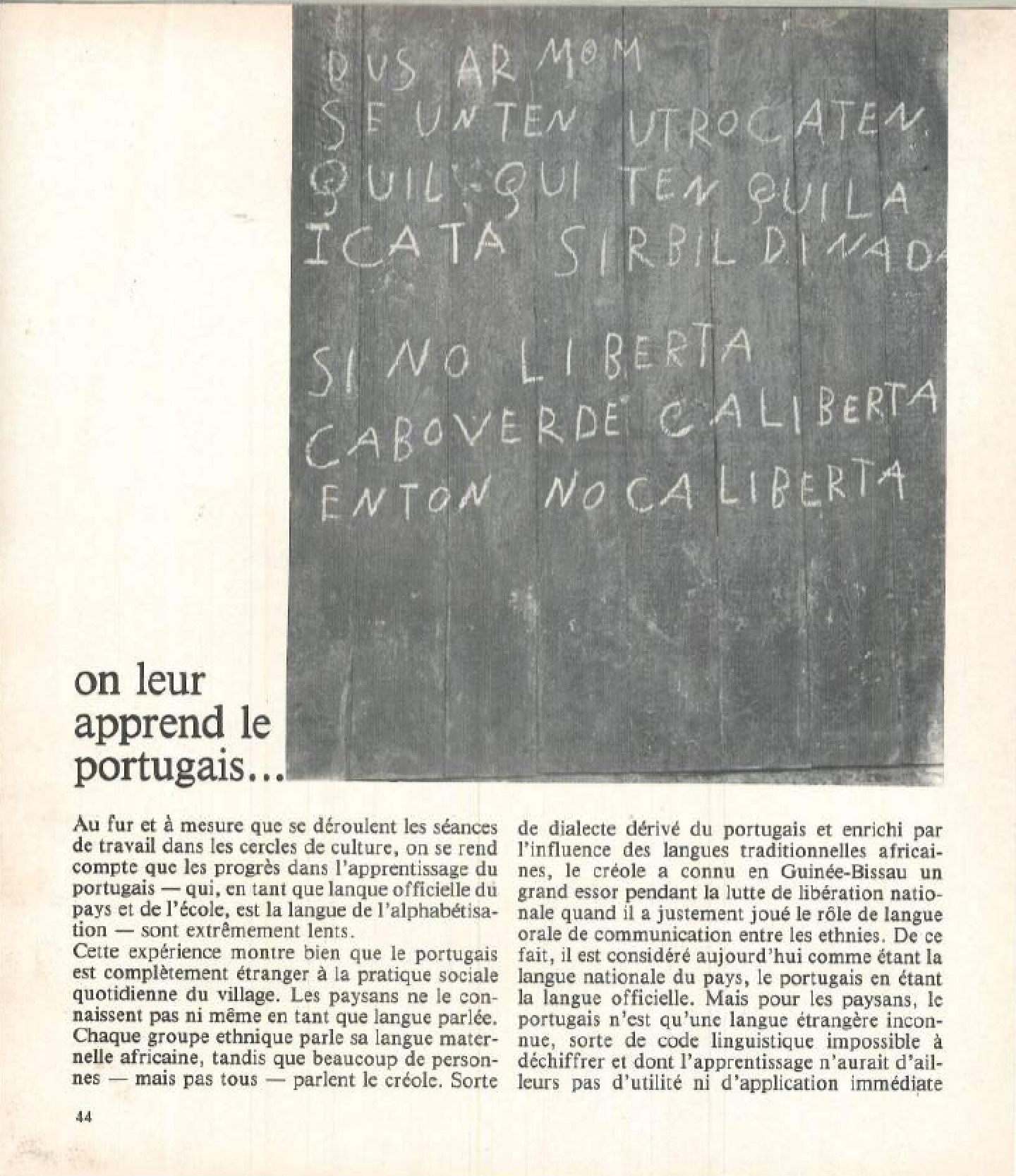

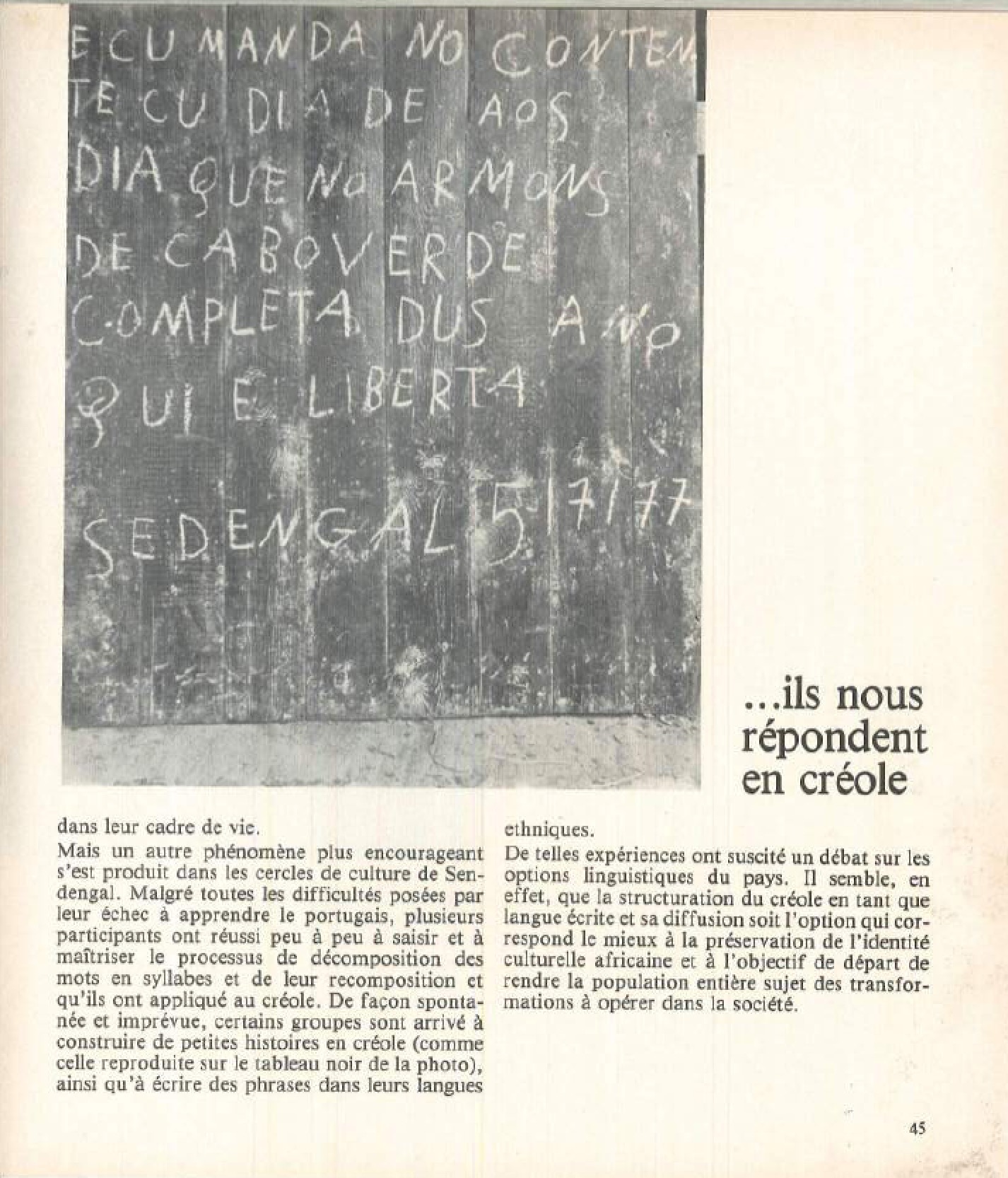

Those programs were not as successful as they were meant to be (especially in Guinée-Bissau). Among other factors, well described by Kirkendall 53 – including the fact that following his reading of Almícar Cabral, and on the contrary to what happened in Brazil and in Chile, he mistrusted the middle-class youth as possible agents to spread literacy – the choice of Portuguese as the language in which the literacy process would take place was problematic. The second IDAC publication around the work in Guinée- Bissau contains a double-page titled “on leur apprend le portugais...” [we teach them portuguese] “... ils nous répondent en créole” [they answer in creole] 54 . Moacir Gadotti explains that this choice was not an impulsion by Freire but was link to the government’s belief that only a common language could unite the country 55 .

A decade later, in Learning to Question: A pedagogy of Liberation 56 , he will answer to Antonio Faundez’ critic of having used the colonizer’s language in Guinea-Bissau in saying he recommended against it and proposed a bilingual approach 57 . In this dialogue with Faundez, he will insist again on the contextual dimension of his approach 58 59 :

It has also been said in connection with my involvement in educational work in Guinea-Bissau that what I have done is simply transplant my experience from Brazil. That in fact is not the case. I advocated in Brazil the idea that adult literacy education is a creative act [...].

[...] our concern has always been not to transmit to them any specific type of knowledge (for knowledge is not transferred, knowledge is created and re-created) but to adapt them to learning a correct method of ‘reading’ changing reality.

This literacy actions in Africa are quite well documented, in particular the ones in Guinea-Bissau, with the publication – in addition to the two IDAC publications – of Freire’s book Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau, in 1978. Their critic have been less accessible and even in his last working report (published in 1980 in the WCC Education Newsletter) he remains ambivalent about the results in this country: “When our advisory service to Guinea-Bissau ends next April, I am convinced we shall have achieved something useful” 60 . The interesting publication A Africa ensinando a gente, from Freire and Sérgio Guimaraes documents, through interviews, work that was done with people who participated in the actions in Angola and Guinea-Bissau and were willing to share their reflections of the experience on the long run. 61

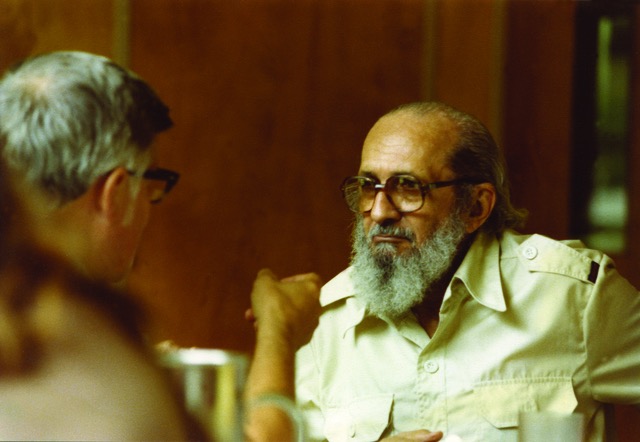

Aside from those official activities, Freire would hold numerous informal meetings – often in the WCC cafétériat, as mentioned in many letters. Gadotti mentions that, in that same space, “[Freire] used to write his articles and conferences and then would give them to us, his friends, so we could critic them.” 62

For example, he would meet with readers of Pedagogy of the Oppressed from different countries and in particular with South–African militants looking for guidance. Pedagogy of the Oppressed was forbidden in South Africa and Freire would sometimes read its content to his guests before they flew back to their country. He explains how deeply he was revolted by the Apartheid regime and refers to Fannon and Memmi as resources for the struggle against this regime.63 Interestingly, Steve Biko was at that time largely impressed by Freire’s book and conception of conscientisation 64 .

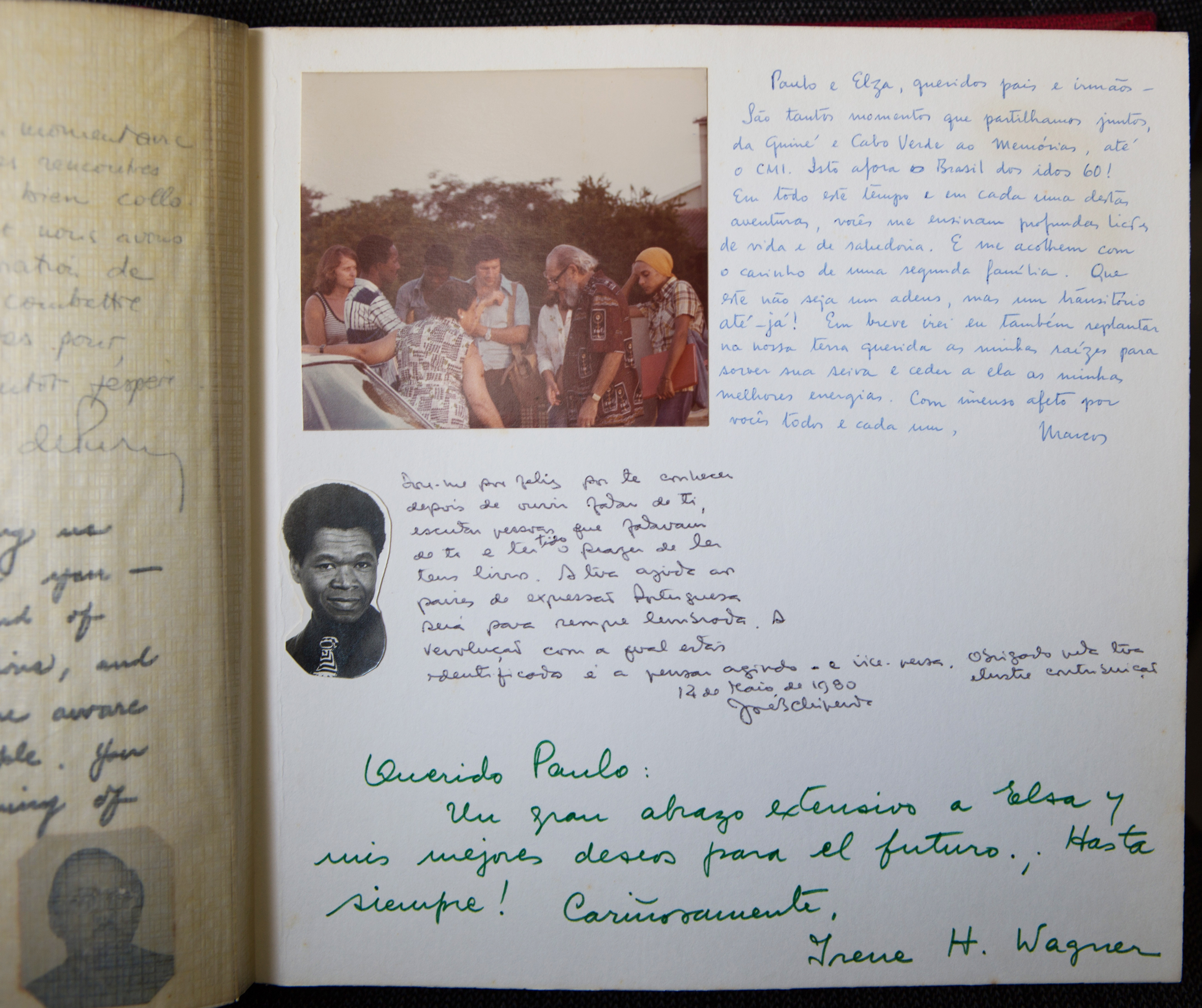

At home, the Freire family would also welcome many people, as his son Lutgardes Costa Freire remembers 65 :

Our flat was always full with Brazilians, Chileans, Bolivians, Latino-Americans. Everybody would pass by and some would stay to sleep, sometimes three days. [...] During the whole time of exile it was like that. We always welcomed political exiles, mainly Brazilians, who had been tortured, who had suffered... So we would help them.

This spirit of exchange and of friendship is also visible in the letters contained in the archives (that constitute only a small part of the written exchange Freire had from Geneva, as, according to him, most of the Geneva archives have been lost 66 , which he regrets “with an almost physical pain” 67 ). Many of the them are not simply administrative or organizational but show a real will to exchange on the conceptual level, on experiences, hopes and doubts. Freire, even though he was sometimes overwhelmed with work, did encourage people he met, in many different contexts, to write to him. Indeed, he received letters of people reminding him that he told them “please do write to me 68 ” or saying “You asked me to start writing. I am happily obeying your suggestion” 69 . Moreover, many people he met (or who met him through his books) write to express their sympathy and sometimes consider him as a “‘Big Brother’ (not in the Orwellian sense)” 70 , a friend 71 , a father 72 , or seem almost hypnotized “but Paulo, I will never forget your eyes” 73 .

In August 1979, after some political evolutions in Brazil, he is granted a passport and can travel to his home country. He does so once more in March 1980 and then finally returns permanently in March 1980. About his years in Geneva and at the World Council of Churches, Freire writes : “This has been one of the best times I have had in my life. This house gave me the possibility to walk without being afraid [...] I became precisely what I have been – Paulo Freire” 74 .His colleagues, in the farewell book 75 they offered him, underline how he was “always creating an atmosphere of curiosity and critical conscience” and how important it was that “’Pedagogy of the Oppressed’ became [in Africa] too, a method for liberation through conscientisation” 76 .

In this part of the Learning Unit, we looked at how Freire used Geneva as a springboard to open a worldwide dialogue around his ideas. We did so, mixing existing writings, unprecedentedly used archival material and testimonies that we collected through exchanging with different people. In the following “sub- Learning Units”, we will articulate experiments that were held in Geneva and Zurich to reengage Freire’s thinking today with other historical elements that connect Paulo and Elza Freire to the city of Geneva more directly, and about which less research exists. Through those other examples, we emphasize how Freire’s thinking did circulate in the city and had some profound effect for some people, despite his presence having left very few visible traces.

3. REENGAGEMENT EXPERIMENTATION – INTRODUCTION

As stated above, one of the main goals of our research is to experiment ways of reinventing Freire’s thinking to for it to warrant reengagement – especially by gallery educators – in Switzerland today.

To develop a dialogical project – following Freire’s approach – and to multiply the experimentations, we invited three Geneva-based gallery educator collectives to form a praxis group with us. All of them (who will be presented later, are either independent collectives or representatives of alternative cultural spaces). None of the participants were familiar with Freire’s texts before the project. Camilla Franz, a Zurich based gallery educator who is a member of intertwining hi/stories network (and who was already familiar with Freire’s writing) joined the group with a fourth experimentation. This long term collaboration with a group of young people who arrived in Switzerland with the status of Asylum seekers began months before the ones in Geneva began under different modalities, as part of the Intertwining HiStories cluster.

We first met with the gallery educators for a long session that involved reading some of Freire’s texts together and discussing them. In particular, we used chapter three of Pedagogy of the Oppressed 77 and summarized it in the document that we copy below.

Each group then imagined an action – often extending or transforming a part of their usual practice – to develop a practice or thinking that would somehow echo Freire’s approach and to somehow continue in the direction of the work Freire undertook in Geneva when working with migrant people and when supporting, with the IDAC, feminist actions.

We met each group individually once or twice to discuss each experimental project, the experimentations were realized (over a four month span) and we reconvened all together in the end to pool our experiences.

In the following pages, four “sub-Learning Units” are organized around four themes and are each presenting one of the experimentations, articulating it with a historical fact linking Freire to Geneva and discussing its relation to Freire’s thinking. Some very open leads to translate each experimentation to other contexts are also suggested.

EXAMPLES OF FREIRE’S CONCEPTS TO REINVENT/REENGAGE

In the third chapter of Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 2001), Freire presents a quite detailed plan for establishing a dialogical education, by taking the example of literacy campaigns that were led under his impetus in rural areas of Brazil’s Northeast Region during the 1960s.

Above all, the exchange begins with a search for a meaningful theme for the oppressed learners, the generative theme. In order to identify this theme, an interdisciplinary team of researchers (art, education, sociology, political studies) undertakes field trips and through conversations with the inhabitants of a place (who are invited to take part in meetings and become assistants to the research) and observations of even seemingly insignificant factors, the team members fix their critical gaze on the area under study as if it were for them a sort of ‘coded situation’, a unique case that challenges them (2001:99-100).

In the second phase, the researchers share their accounts, with each other and with the representatives of the population, during appraisal meetings. The sharing of observations and the discussions enable the identification of a nucleus of contradictions that sits at the heart of daily life for inhabitants in that study area.

Next, the team uses these contradictions as the basis to produce codifications. Freire recommends various forms for this codification, which may be visual, pictorial, graphic, tactile or audible, depending on the subject to encode, but also on the individuals to which it is addressed, according to whether they have experience of reading or not (2001: 112). They will function as tools, in the pedagogical process, to identify with local people the generative themes (of which the analysis will enable learners to begin a critical reflection about the world in which they live). These images must necessarily represent situations known to the individuals whose themes are being sought [...] (2001: 103-104) and must function as challenges upon which to bring a critical reflection (2001: 103-104).

Then, the ‘pictures’ are ‘decoded’. This decoding – which forms part of the ‘educational programme’ itself (within the research circle) must enable the participants to view their idea of the world in a different way, to review fatalism and to foster the emergence of an untested feasibility (2001:102), that is, a hitherto an unimaginable action that may be accomplished.

It is through this process that what Freire calls, ‘education oriented towards problem-posing’ (and ultimately conscientization) develops. With this form of education, the people involved develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with which and in which they find themselves. They come to see the world not as a static reality, but as a reality in process, in transformation (2001:99).

PART 2

A) TOWARD A FEMINIST CONSCIENTIZAÇÃO

A1) A MORE INCLUSIVE WRITING – NAMING WOMEN AND ACKNOWLEDGING ELZA FREIRE’S ROLE

Some of the critics to Freire’s work 78 were linked to the fact that Pedagogy of the Oppressed is “striking in its use of the male referent” and that he would consider the oppressed, in a universalist approach, as “undifferentiated” and “the source of unitary political action”, failing to answer questions such as “How are we to situate ourselves in relation to the struggles of others?“ or “How are we to address our won contradictory positions of oppressors and oppressed” 79 . His work has nevertheless not been rejected as a whole by feminist thinkers – sharing his goal of liberation – and some arguing or acknowledging his work in order to make a feminist use of it. bell hooks writes: “I think it’s important and significant that (...) Paulo recognizes that he must play a role in feminist movements. This he declares in Learning to Question: 80

If the women are critical, they have to accept our contribution as men, [...] because it is a duty and right that I have to participate in the transformation of society. Then, if the women must have the main responsibility in their struggle they have to know that their struggle also belongs to us, that is, to those men who don’t accept the machista position in the world.

During his years in Geneva, he becomes more aware of feminist thinking and take some action to change both his writing and actions accordingly. Freire explains 81 that, in 1970 - 1971, just after the publication of Pedagogy of the Oppressed in English, he would receive “almost uninterruptedly” critical letters from North American women who invariably praised the fact that his approach of liberation was a contribution to their struggle but also criticized the fact that a “sexist and therefore discriminatory language in which women had no place” was used. He recognized their letters as being full of “just indignation” and this leads him to consider that the fact that “men” includes “women” but that “women” doesn’t include “men” is not a grammatical problem but an ideological one and will from there “always refer to ‘woman and man’, or ‘human beings’”. If this formal change doesn’t address the more complex critic of universalism mentioned above, it does show that Freire was sensible to those critics and open to bring some transformation in relation to feminist reflections.

And this evolution doesn’t concern only his writings. Indeed, as we have seen above (see Vagabond of the Obvious), developing experiences with the feminist movement in Switzerland was one of the key actions developed by the IDAC. In the four IDAC publications directly dedicated to such actions 82 , only the female collaborators are directly involved. Nevertheless, one can imagine that those were imbued by discussions within the larger group and by Freire’s texts. This is especially visible in the pedagogical experiment described in “Féminin pluriel (I). De l’éducation des femmes” (“Lire sa propre réalité, écrire sa propre histoire” 83 [Read one own’s reality, write one own’s history] ; “faire le relevé de ce que Paulo Freire appellerait l’univers thématique des femmes habitant l’ensemble résidentel” [record what Paulo Freire would call the thematic universe of the women living in that housing project]).

During the 1970’s, Paulo Freire would also begin to give more and more attention to recognising the role of his wife Elza, not only in his life but also his work, in particular around Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Indeed, if Elza Freire’s role is seldom mentioned in the literature on Paulo Freire, he was nevertheless himself very attentive to underline her role. In an interview in 1974, he says: 84

I think that without Elza it would have been a very difficult task for me to have written the book [Pedagoy of the Oppressed]. [...] she exercises a strong influence on me. She studied with me and was a teacher of Portuguese [...].

In Pedagogy of Hope, he will confirm: 85

Finally, I owe one last word of acknowledgment, and posthumous gratitude: To Elza, for all she did in making Pedagogy a reality. [...] Elza was always an attentive and critical listener, and became my first, likewise critical, reader when I began the phase of the actual writing of the text. Very early in the morning, she would read the pages I had been writing until daybreak, and had left arranged on the table. Sometimes she was unable to contain herself. She would wake me up and say, with humor, ‘I hope this book won’t send us into exile!

Elza Freire is also very often mentioned as a collaborator in the letters sent by Paulo Freire at the WCC and he would write for example “the programs that Elza and I are working in are in several African countries” 86 or “Elza is participating in the different programs in Africa and I’m extremely happy about that” 87 .

In a text published in 1982, Elza Freire talks about her key role in the early development of the literacy approach often referred to as “the Freire’s method” : 88

We did it together, Paulo and I, the literacy work in the Nord Este. I stayed with the methodological part, with the elaboration of the thing. The parish where we lived gave us a space where we gathered five workers who lived nearby. With them, we were preparing, we were testing. As we knew well the area, the neighborhood where we lived, this gave a lot of possibility to see if it worked or not. We noticed that they wouldn’t understand certain things, we eliminated some more difficult words and we realized that there would be an advantage in using words that had three syllables and not only two, because they gave us the opportunity to generate other words

And she underlines that this practical dimension of teaching was precisely her competence and this was key in the development of what would be later identified as the “Sistema Paulo Freire”: 89

I had the primary course with children. I was really specialised in literacy for almost ten years [I was working with] twenty- eight words generated from the child’s world and they were giving a fabulous result. So, we thought: what if we transferred to the adult world, what would it be like? [...] I saw that it worked, because the adult was as much interested in the generative words of his world, as the child was interested in the “ball”, in the words linked to the games in her/his world. And surprisingly, the adult visualized faster than the child.

Cristina Freire Heiniger 90 .] also tells the key role her mother played in the development of the literacy tools:

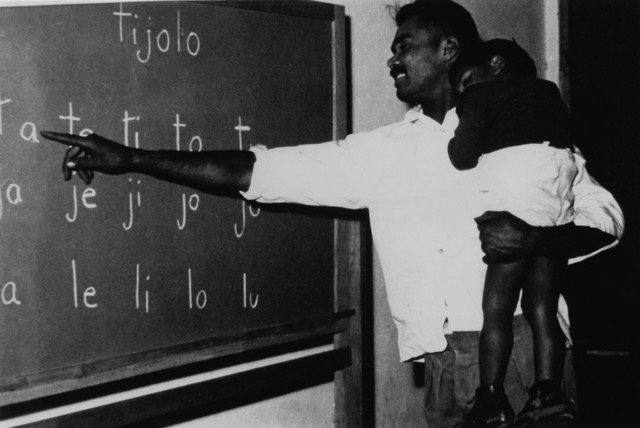

She was a teacher since a long time. It is my mom who did the literacy work, never my dad! It was her work, she taught children at school to read and write. I read that my dad regretted never to have taught children. He always taught to adults, at the University. The whole part of the “Freire method” dealing with literacy itself, it was my mom! For example [...] my dad wanted to use, as a first image to be codified, “pássaro”, “bird”. It made her hair stand on end: “Pauli [...] this double “S” is one of the main difficulty of our language”! She said “we must take examples from the everyday, I completely agree, but we must choose more simple words”. So they began Ti-jo-lo.

And she adds 91 .] that after Paulo Freire decided to quit law to engage in studying education, Elza would not only support her husband in his choice but also support the family economically (they had two daughters at the time), later calling herself the “first feminist in Recife”!

In the same discussion, Cristina Freire Heiniger, in a more anecdotal way (even though it is quite revealing of how history is too often written), says that, on the contrary to what is written in the menu of the restaurant Le Portugais (see note 11), it is Elza and not Paulo who taught to the wife of the owner, and not the owner, how to cook feijoada. And she adds “I remember he was doing the dishes. That was thanks to the feminist movement. He couldn’t boil an egg but he was clearing the table and doing the dishes...”.

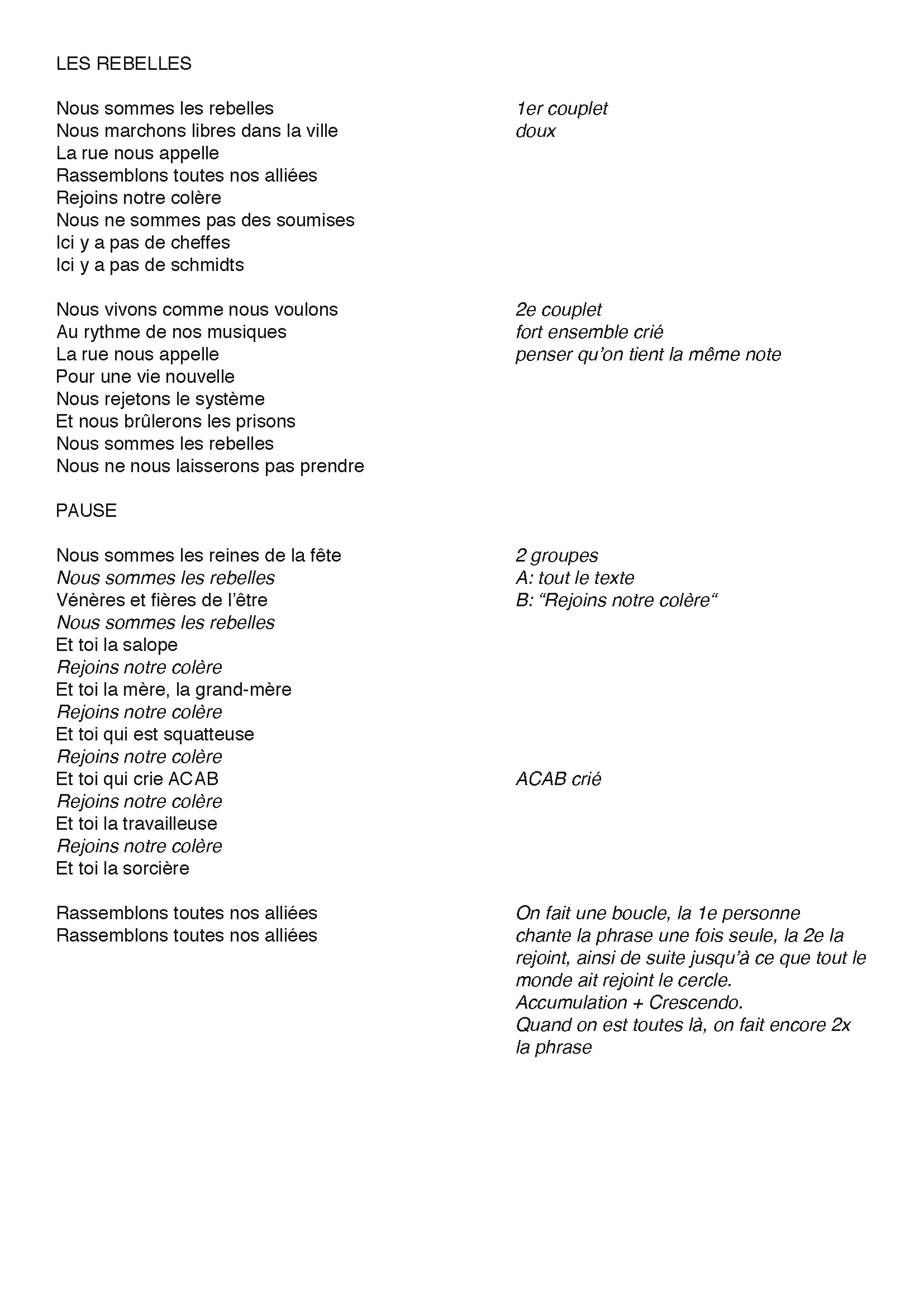

A2) RE-INVENTION / REEGAGEMENT EXPERIMENT: FEMINIST CHOIR

PROJECT

The Feminist Choir is a project developed by the TU – Théâtre de l’Usine, in the frame of a program focusing on voices. It is coordinated by the performer Charlotte Nagel. The choir is aimed at voicing protest, rage and feminist becomings through songs that were produced collectively. So far, the choir met four times for rehearsals (were the participants ate together and could use the childcare service) and performed two mini-concerts.

ADDRESS

The Feminist Choir is composed of ten women who signed up through an open call (in which it was specified that no competence in singing or music was required). It performed in Geneva cultural events or demonstrations.

STEPS

- During the first meeting, the coordinator brings a recorded song. After listening to it and reading the lyrics, the choir sings together over the song that is played. At first, the song is played loud, to help the participants not to be shy. Gradually, the volume is turned down (an acapela version is sung at the end).

- The lyrics of the song are discussed together: does the choir feel at ease with them? How could these be rewritten, re-appropriated, so that they become the choir’s own? How can they become acceptable in terms of gender and postcolonial perspectives?

- The participants are invited to bring other songs to work with in the following sessions.

- A song is selected together and is rewritten, arranged and performed publicly as a group.

The first song selected by the choir was “Les rebelles” by the French punk-rock band Bérurier Noir.

Examples of the transformation of the lyrics are:

Nous vivons comme en Afrique/Au rythme de nos musiques/La jungle nous appellee

[We live like in Africa / Following the rhythms of our musics/The jungle is calling us]

Nous vivons comme nous voulons/Au rythme de nos musiques/La rue nous appellee [We live as we want/ Following the rhythms of our music/The street is calling us]

Et toi le gladiateur!/ Rejoins notre raïa/ Et toi le déserteur! Rassemblons toutes nos tribus! [And you, the gladiator/Join our raïa / And you the deserter! Let’s bring all our tribes together]

Et toi qui crie ACAB / Rejoins notre colère / Et toi la travailleuse /Rejoins notre colère / Et toi la sorcière

[And you who shout ACAB / Join our anger / And you the woman worker / Join our anger / And you the witch]

Those transformations aimed at removing some exotic tainted stereotypes used in the original song and to address women directly.

The Choir continues developing its repertoire, considering adding its own songs to it and aims at inspiring other similar project through its performances.

LINK TO FREIRE’S APPROACH

The project is inspired by Freire’s idea of awakening a “critical consciousness” 92 through a dialogical pedagogy (enhanced here by a strong feminist approach). It is also based on the idea of “struggling to have a voice of one’s own”. 93

Every step is developed through an exchange amongst all the participants – regardless of their musical skills – and the goal is to develop a sufficiently critical reading of a song for the group to be willing to transform/ re-appropriate it through an empowering collective “out of tune” performance.

The experimentation was an attempt to overcome Freire’s universal approach criticized by feminist thinkers (see above) in re-appropriating songs from one’s own position and in questioning the colonial dimension of the lyrics. But, the members of the choir also noticed their homogeneity in terms of “race” and socio-cultural background, and questioned their legitimacy to produce counter-colonial proposals from their privileged position. They changed the lyrics of the original song, which proposed an exoticized vision of Africa. This reflection could lead to re-discussing Freire’s use of “class consciousness” and of “conscientisation” with a less universalist and more intersectional approach.

A3) IDEAS FOR POSSIBLE TRANSLATIONS

- In a group, pick a song you can identify with but which nevertheless has parts you would like to criticise. Discuss them and write alternative ones together.

- Organize a karaoke session in which some groups are invited to sing critical alternatives of existing songs.

- Each member of a group selects a sentence from a song that makes her/him feel bad. The excerpts are read and discusse

B) THEMATIC UNIVERSES IN A MIGRATION SOCIETY

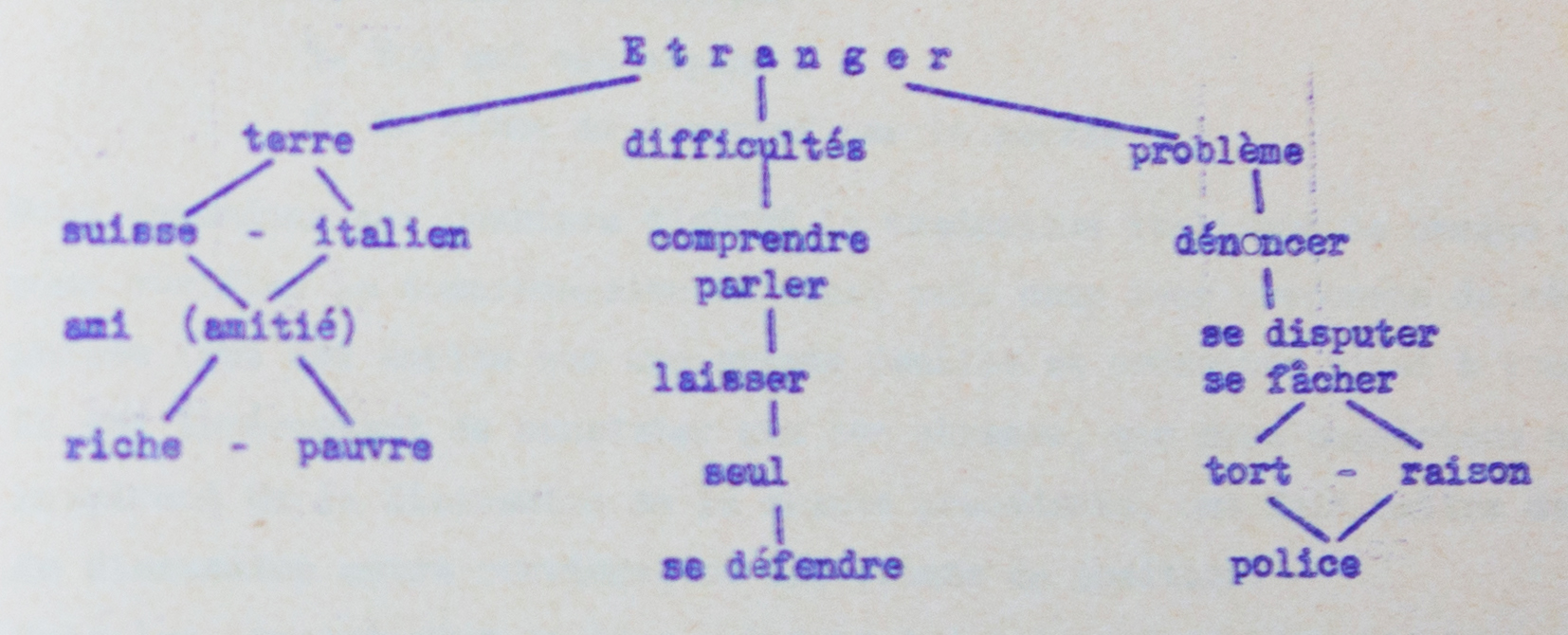

B1) A WORD TREE ROOTED IN FREIRE’S APPROACH

In 1971 94 , Freire helped three students in Education Sciences (Antonietta Pastore, Chantal Depierre and Jean-Marie Kroug) who were transposing his pedagogy to develop a French literacy work with guest workers in the Geneva area.

Moved by the precariousness in which the guest workers were living under in Geneva, the students were willing to get involved in an action to improve their conditions. They first study the work of an existing organisation (le Groupe d’Action pour les Travailleurs Immigrés) which proposed French classes for the workers to provide them with a common language. They observe that classes are not well attended, not efficient and based on a material that is not adapted. Then, through a questionnaire addressed to five workers who took part to the class, they try to know more about their motivations. Part of their conclusion is that a vocabulary that is close to the workers interests and everyday activity should be used and that the fact of not speaking French is a source of trouble and injustice. About these injustices, the phrase “we are strangers, we can not do anything” often came. All seemed to be suffering from the isolation in which the native population left them. 95

They decided to propose their own French literacy course and, through the reading of Paulo Freire (many Cultural Action for Freedom 96 and some articles, as Pedagogy of the Oppressed in not published yet), they invented a “methodological transposition” (“Our methodology is rooted in Paulo Freire’s. Sometimes we will need to take some distance from it, not in its spirit but in the process of it” 97 ). Their proposal was based on the idea of building a vocabulary-universe.

Then, they were able to present their methodology to Paulo Freire in the frame of two meetings, in December 1970 and March 1971. He told them:

Your goal is the research of a scientific instrument to teach French to guest workers. But in fact, it’s not only about a new vocabulary to acquire, it is also a conscientisation.

And he advised them: 98

For your work, you must first choose themes from a concrete reality and observe the ways of talking and living of the dominant class (which always wants to dominate) and of the guest workers. Thus, for example, in decodifying posters related to guest workers seen in train stations, one discovers the language of the dominant class... Then find the generative themes, meaning; try to create a vocabulary that is not selected first for phonetic or grammatical reasons but because it is linked to the content of the lives – and through that to the motivations – of the workers.

He confronts them with a choice: 99

[...] you can stay on the teaching level only, give them the linguistic skills so they can communicate or you can go deeper and, with this linguistic skills, make it possible for the workers to become conscious of the value or of the alienation of their work.

The students will then develop a series of two hours sessions held over 12 weeks for five Italian workers who volunteered. They begin each session by proposing a theme. The theme (for example “work” or “stranger”) are linked to their everyday experiences and are a way to open a discussion (in Italian at the beginning). Then, the workers propose words connected to those themes. The words are organised into a “tree” and, after a few sessions, the participants are able to form their own sentences by picking a words from the tree, writing them on small cardboards and playing with them. In their initial planning, some drawings were supposed to be used – echoing the visual dimension of Freire’s approach. Nevertheless, due to the difficulty to illustrate many of the too abstract words proposed by the workers, this part was abandoned. Even though the authors don’t comment it, a clear dimension of political conscientisation is visible in the example chosen by the educators or formed by the workers (“Le maçon fait beaucoup de choses” [The mason is doing many things] 100 “Le travail ne me plait pas” [I don’t like the work] 101 “Le riche ne comprend pas le pauvre” [The rich doesn’t understand the poor] 102 “L’Italien répond au chef” [The Italian is answering the boss] 103 ).

The results were quite encouraging, both in terms of language skill and of social transformation (as they noticed modes of exchanging that were getting more convivial) and the project was set to continue, at least for a few months. The students nevertheless emphasised that their work was not in any case a solution to the injustices that the guest workers suffered, as it was only a needle in a haystack and as such the practice – if developed by ill-intentioned people – could lead to the assimilation of those workers in the “established disorder” 104 . Therefore, they insist that their experiences should remain experimental and not become a model, as they believed that it could inspire other people to develop their own actions.

B2) RE-INVENTION / REEGAGEMENT EXPERIMENT: COMMUNITY GARDEN

A project developed by Super Licorne

PROJECT

Since 2015, Super Licorne association proposes different activities –including artistic workshops – to the inhabitant of the Foyer des Tattes, a residence for asylum seekers in the Geneva area. In 2017, it took over a community garden program, managed by the institution the Foyer des Tattes dependent on: the Hospice Général, which was began the preceding year and that was – according to the association – more a communication strategy than an effective project. Super Licorne invented strategies to overcome the structural limitations imposed by the Hospice Général, with the will to develop a truly collective process.

ADDRESS

The Community Garden project is addressed to the asylum seekers’ families living in the Foyer des Tattes. Contrary to what was done before the project was taken over by Super Licorne, children were also welcome.

STEPS

The inhabitants are first invited to take part in collective meetings to imagine what a community garden could be and how it could be organized.

What does it mean to attribute a parcel of land to people who are stateless? Which vegetables are suitable to grow when many people come from other climate zones and know other kinds of vegetables? What does it mean to talk about urban agriculture with people dreaming of having their own cultivable land? What does it mean to organize collectively when people have only limited access to the basic resources (like access to the garden water’s tap)? What does it mean for the coordinators to work as gardeners paid 45CHF/hour, when the average salary of the inhabitants is 3CHF/hour (a salary they receive from the Hospice Genera if they take care of the cleaning of the foyer, for example)?

The association aims at addressing key political and social questions but in an indirect way, seemingly raising only very concrete questions related to a practical common goal: growing vegetables.

During the meetings, the visual dimension – that the association developed during their artistic workshop in the same context – is key. They re-appropriate a vegetable calendar to produce posters that stay in the room in which they meet to organize the work. Through those posters – mixing written basic information about the vegetables, images and handwritten comments resulting from the discussions – organisational issues are raised and decisions are made. Thus, the project is reorganised in a way that land is not simply split into individual parts anymore but according to the different vegetables grown, leaning on an approach close to permaculture, the vegetables are thereby shared communally once produced. A strong emphasis is put on the pedagogical dimension and many skills (from agriculture techniques to literacy) are shared through working sessions between all the gardeners (inhabitants and educators). Moreover a specific part of the garden is reserved to children, to encourage a learning-by-doing approach.

A way to collectively produce a (visual) discourse on the project – which avoids the pitfalls of staying at the level of institutional promotion – is currently being thought by the group.

LINK TO FREIRE’S APPROACH

The use of the posters as generators of discussion is directly inspired by Paulo Freire’s use of visual material that worked as “codifications” (usually pictorial or photograph material) of everyday reality that were to be decoded with the learners and to generate exchanges and learning 105 .

Freire’s idea of “Reading the word and reading the world” 106 is here embodied in learning practical information about the vegetables (names, seasonal cycles, recipes) while simultaneously thinking about how to collectively organise to improve one’s life in a situation of exile.

B3) IDEAS FOR POSSIBLE TRANSLATIONS

- With a group of people who have experience working together, list a series of points that have been problematic in the past. Display those questions on a board and illustrate them. Leave the board in the working space and let people, from time to time, individually or in small groups, add comments to the composition and discuss it.

- With existing printed material about a specific topic that is important to the participants, organise a collage session. Use the compositions as a way to generate discussion topics.

- Being part of an existing project, propose to use open budgeting to the collaborator. Whatever the decision is to use it or not, organise discussion sessions around the questions the proposals will generate.

C) READING ONE’S WORLD

C1) CRITICAL READING OF THE SWISS SCHOOL SYSTEM

On one of the cards linked to this Learning Unit, we present the anecdote that happened to Flávio the son of Freire’s friend, the architect and cartoonist Claudius Ceccon, also exiled in Geneva in the 1970’s and member in the IDAC, an anecdote related by Freire in Pedagogy of Hope 107 , [Pedagogy of Hope, p. 142.], [Pedagogy of Hope, p. 143.].

One day, the young Flávio comes back from school sad and discouraged. His teacher had torn apart one of his drawings. His father meets her to discuss the case. She praises Flávio, his talent and autonomy. Then, she proudly shows him a series of almost identical cats realized by the pupils from the observation of a statuette. “What do you think of that?“ the teacher asked, and without waiting for an answer exclaimed, “My students did these. I brought them a little statue of a cat for them to draw”. “Why not bring a live cat into the classroom–one that would walk and run, and jump?” Claudius asked. [...] ‘No, no!’ the teacher fairly shouted.

She explains that copy is a way to avoid “terrifying situations for the children” where they must choose and create. Therefore, she couldn’t accept Flávio’s cat, which had “impossible colors”. 108 Freire presents this anecdote as a metaphor of school system as a whole, a system fearing liberty, creation, adventure, risk and leaving no space for transformation: 109

And that, it appeared, was the way the entire school functioned. It was not merely that one educator who shook with fear at the very mention of freedom, creation, adventure, risk. For the whole school, as for her, the world should not change [...] Blaze trails as we go? Re-create the world, transform it? Never!

Freire also relates, with amusement, the way in which books for children – used in schools or not – would warn the children against the danger of exploration. He talks in particular of the story of a little piglet who, by curiosity, decides to set out for the day and experience a series of catastrophes. When he comes back his father “wisely tells him, with the benign air of a gentle pedagogue, ‘I knew that you would do this some day. For you, there was no other way to learn that we need not leave the beaten track. Try to change something, and we run the risk of being hurt very painfully, as must has happened to you today’.” 110

If more than ten years after going back to Brazil Freire voiced some critiques against the Swiss school system – through anecdotes that sport a mix of seriousness and amusement – it seems that he had another attitude while in Geneva.

Indeed, his son Lutgardes Costa Freire 111 relates:

I hated Swiss school, really. It was hard, I was a bad student, I couldn’t get my degree. School was very tough, very strict. [...] On the first day, I came back home and I told my father ‘I’m not going in this school anymore’. He asked me why and I said ‘I don’t want to become a machine’. He told me that I was causing a terrible trouble to him and I answered ‘but you think like that! How do you want me to go in a school that is the contrary of what you believe in?’. But he would say ‘look son, I cannot change Swiss school, I am welcomed in this country. If suddenly it is thought I cannot stay here, I will be expelled. And where are we going to live?’”.

If Freire would not attack (nor comment) on the Swiss school system while he was in Geneva, he would still obtain the authorisation for his son to be taught by teachers at home. In addition the IDAC (without mentioning him in the issue’s editorial teams but making many direct or indirect references to his writings) Freire published two very critical issues about schools in general: “Attention école” 112 , which is based on a collection of Claudius Ceccon drawings caricaturing the reproductive school system and “École, société, avenir”, which is criticised the “false changes taking place in schools” and presenting a series of alternative modes of education” 113 . In the final text of the second publication (written be Miguel and Rosiska Darcy de Oliveira), one can read: 114

It’s about reversing the whole logic [...] an education that would not only be the individual acquisition of competences and techniques [...] but a collective process of acquisition of knowledge and modes of being, useful for the better being of the whole community. [...] An education that would not be limited to the transmission of specialised knowledge so that everyone could have a place within the hierarchised society, but whose goal would be to train autonomous and versatile individuals, able to live in communities that would be lively, conflictual, self-determined and, because of that, in permanent mutation

C2) RE-INVENTION / REEGAGEMENT EXPERIMENT: WE TUBE

A project developed by the ART SANS RDV

PROJECT

The association of art educators ART SANS RDV developed a construction game that can take place in different neighborhoods, on the living site of the participants. Through working with recycled and reusable materials, the participants are engaged in a process of observing and rethinking their environment through a collective process.

ADDRESS

The building material kit is transported in a recognizable cart in a neighborhood (Le Chapelle in Lancy, Geneva for this pilote project) during an off-school day. Children (and possibly their parents) are welcomed to join the activity freely as they see the device arriving in front of their homes. The workshop is also announced a few days in advance with posters and through social networks.

STEPS

A construction kit is prepared in advance and brought by the educators. It consists of cardboard tubes of different sizes in which four holes are made on each end (to allow them to be connected with screws or strings).

The kit is brought to the neighborhood.

When people arrive and groups are formed, a discussion takes place to delimit a working perimeter (outside). A discussion takes place about what the participants observe in that space and about what they would like to see transformed there.

Individually or in small groups, the participants use the tubes to build either a real size cardboard version, or a model of something they would like to build in that space.

At the end of the process (after about 90 minutes) the different structures might be connected together to form a common installation. While sharing a snack, a discussion is held about what was produced, opening to more general questions about the perception of the neighborhood by its inhabitants.

The productions are documented through photographs (that can be turned into schematic drawings afterwards), to build a catalogue of modular forms for each place in which the workshop took place.

The process is meant as a way to open a dialogue and favour interactions between different people living in the same area (particularly between Swiss citizens and migrant people), using play as a way to overcome language barriers and to share competences and perspectives.

LINK TO FREIRE’S APPROACH

Art sans rdv feels the need to develop educational experimentations outside of schools. But the association also aims to adhere to the socio-cultural diversity that a school context would offer. Therefore, instead of developing activities around art inside cultural institutions, they try to find other frames to do so, like popular neighborhoods.

The group borrows from Freire’s idea of “Untested feasibilities” 115 . For him, the pedagogical process must lead the people involved in it to change their perception of the world, to overcome fatalism and to the expression of “Untested feasibilities”, meaning “previously unperceived practicable solutions to a problem”. Through the process, Freire thinks that people “develop their power to perceive critically the way they exist in the world with which and within which they find themselves. They come to see the world not as a static reality, but as a reality in process, in transformation”. 116

Freire writes: “To investigate the generative theme is to investigate people’s thinking about reality and peoples action upon reality, which is their praxis” 117 . In this project – even if the alternative construction remains on a symbolical level – a similar two-dimensional approach is developed: observing and thinking what one’s reality is and forecasting possible transformations.

C3) IDEAS FOR POSSIBLE TRANSLATIONS

- In small groups, define 3X3 meters squares in a given area. Find a way (with tape for example), to make the limits visible. Describe as many things as possible in this square, for a set time of 30 minutes for example). Each group present its observations to the others. Discussions are held about what should be transformed in those spaces and about what would be needed to make those transformations possible.

- Using only one simple geometrical element that is reproduced, the first person draws a composition that evokes a story, personal or not, that is important for her/him (around a topic selected collectively). She or he passes the drawing to someone else. This second person proposes an interpretation, aloud, without the person who made the drawing intervening. An exchange takes place on the differences between the initial intentions and the interpretation... What was misleading? What was interpreted one way but was meant as something completely different? Another person draws a story and the process continues. A booklet with the drawings and double-stories can be produced at the end.

- With the inhabitants of a given building/urban area, draw, on existing plans or photographs, utopian transformation proposals. Make posters with the proposal and display them in the neighborhood.

D) TOWARD A MAGICAL FUTURE

D1) OTHER POSSIBLE FUTURES FOR ILLEGALIZED CHILDREN

In one of the cards connected to this Learning Unit → Un/Chrono/Logical Timeline # MIGRATION SOCIETY / # COUNTER-SCHOOL, we talk about a “challenge school” or “counter-school” that Spanish workers presented to Freire. Through it, migrant parents wanted their children – for a few hours per week in parallel to their official training in the Swiss school system – to problematicise the Swiss school – which they viewed as reproducing the dominant ideology. Their reading of Pedagogy of the Oppressed (after having read Fanon and Memmi) had confirmed their pedagogical intuitions and they were asking for advices to Freire in moving forward with their project.

Freire talks about this exchange in Pedagogy of Hope 118 and we could find no other information about it so far. Nevertheless, trying to do so, we learned about another teaching project involving Spanish workers, in which Freire was directly involved.

We heard this story from Alberto Velasco 119 , socialist deputy to the Geneva Grand Council since 2013 (but he says that his greatest political achievement was to taking part this pedagogical experiment and not to being elected an MP).

He first tells us about his past as a foreign schoolboy in Switzerland and the difficulties he experienced, the mockery, the sidelined, the need to always have to do better than others to be accepted. He also tells us about medical visits for hundreds of migrant workers held in hangars when arriving in Cornavin, over fears that foreigners would bring diseases to Switzerland.

He then reminds us of the prohibition of guest workers at the time from bringing their families (as

those foreigners were only recognized as part of a work force), the difficult living conditions they were experiencing, living in barracks and the absence of prior significant schooling for the majority of these workers. He also underlines that in the 1970’s (on the contrary to the current situation) children who were in Switzerland illegally couldn’t attend school at all.

He – a Spanish national born in Tanger – arrived in Switzerland at age 13 and quickly took part in a communist and anti-fascist youth movement. Along with comrades, they would go into the barracks where guest workers lived on weekends to talk about the political situation in Spain while listening to the Spanish Republican anthem and drinking beers. He discovers the hard conditions in which those workers lived, the lack of training and perspective for them. Despite the difficulties; latent xenophobia (the school told him that despite having excellent academic results, he could only become a mason if he worked hard at school) and family pressure, he ends up, after an apprenticeship in mechanics, going to University. There, he meets a Spanish Christian teacher, Alberto Pérez de Vargas, who gives evening classes in physics. He obtained attribution to the Spanish community in the form of a small house belonging to the church in the center of Geneva (Place du cirque).

Pérez de Vargas asks Velasco to give math lessons to young Spaniards ... He accepts and discovers a whole world: a community in which the majority of the parents didn’t finish their obligatory school, and in which children who accompanied their parents illegally in Switzerland were hiding under their beds for fear of being seen.

With a few friends, they begin to teach several disciplines, Spanish, French, mathematics, physics. Only a symbolic contribution is required to pay for the material and the learners are involved in the self- construction of different pieces of furniture, including blackboards.

The courses are aimed at children first but, quickly, the parents join them. Thus, both parents who never had the chance to get education basics in many disciplines, as well as children who – because of their illegal status – had no other educational opportunity would learn together.

The young volunteer teachers – who have no previous experience in teaching – feel that they do not necessarily have the right working tools. They learn that Freire (who is already known worldwide at this time) is in Geneva and they ask him for advice. For Velasco, he was the only person able to help them for several reason: he had the experience of working with oppressed people, he was sensitive to difficult questions such as the shame of not knowing which some parents were experienced in front of their children. He also spoke Spanish and his position at the WCC helped them to get support, to find rooms, etc.

For months, on Saturday afternoons, during informal seminars (“He hated academic settings, he loved to exchange, he couldn’t stand that people would see him as an idol, we immediately saw that”), Freire would meet the educators, listens to them, to their problems and gives them advice by telling them about his own experiences.

He helps them to deal with the issue of age disparity among learners (including taking care to respect the dignity of parents when they cannot answer) and to find ways to install a culture of dialogue during the courses. A freedom of speech is installed, which allows for carrying out political discussions, in a climate of dialogue, without stigmatizing but by striving to value mistakes as a source of knowledge production and to value the know-how of each person (every participant being quickly able to find a way to help others to learn through varied approaches).

These educators, immigrants themselves, feel very proud to work with one of their own who is recognized worldwide as a high-quality intellectual and who also speaks Spanish.

After two years, participants can usually read, write, count and master basic principles in physics. In addition, they self-manage cultural moments when they play theater or have musical activities. Some even pass their Spanish school certificates from the consulate in Bern.

The participants are very thankful and acknowledge a generosity that they often never experienced before. In the sense of Freire, “they become the subjects of their history”.

Soon, there are about 300-400 participants in the school and bigger premises have to be found. The group of learners also becomes a real political force because the participants would listen, for example, to calls of protests, when formulated by teachers they trust. The experiment lasted between 1970 and 1975.

Velasco says: “Without him we would certainly not have come such a long way and achieve so much” (and a good example of how Freire’s thinking had a direct effect in Geneva, is that he developed similar strategies years later while working for the Geneva Albanian University).

D2) RE-INVENTION / REEGAGEMENT EXPERIMENT: ZACKIG ZUKUNFT ZEIGEN

A project developed by Camilla Franz in Zürich.

PROJECT

The group “Zackig Zukunft zeigen” worked since February 2016 with the gallery educator Camilla Franz, first within the gallery education program of the Johann Jacobs Museum and then at Raum für autonomie und ferlernen in Zürich. The project addresses the notion of fluid identities and raises issues linked to job opportunities for minor asylum seekers in Switzerland.

ADDRESS

The group is composed of 8-10 boys, between 15 and 18 years old, who are asylum seekers (with different residential permits and stations in the asylum process) all being in Switzerland (Luzern, Aargau, Zürich) non- accompanied.

STEPS

- A several months-long collective reflection on identities, self-representation and job opportunities for young asylum seekers leads to the production of photo-postcards (with pictures and slogans) that tell stories about possible professional futures.

- The event “Zackig Zukunft zeigen” is organised to present the project at the Johann Jacobs Museum. It gathers 75 guests from mixed backgrounds (friends and schoolmates of the participants), cultural workers and city workers working with migration, artists, gallery educators...).

- The group develops a radio program around the topic of asylum and work, in interviewing for example, on the 1st of May, people about their work situations and their political engagement. The work leads to concrete actions taken to try to improve the personal situation of some of the minor asylum seekers, in particular in writing letters to different official structures.

- “Zackig Zukunft zeigen” continues to meet about once every three weeks and produce pictures together. A work on photography is developed, to continue the reflection on self-representation and tackling more specifically the question of self-perception and outer-perception. Work of artists around those topics are discussed (“Bo’sun Driving the Forward Winch” (Fish Story Special Edition by Allan Sekula, 1993) or “The minister of...” (by Kudzanai Chiurai, 2009) for example) and dealt with in various practices of depiction.

- Portraits that will be used for the participants’ CVs are shot. A multivocal map of Zürich is also produced. It shows important places in the everyday life of the participants.

- Finally, after looking at the work of Jean-Michel Basquiat, a collective visual work aimed at bringing together the findings/knowledge produced during the whole process is produced to open up discussions with the public and be displayed in various context. . It is currently presented in the main hall of the “raum für autonomie und ferlernen”.

LINK TO FREIRE’S APPROACH

The second part of the project is linked to a reflection on Freire’s position regarding what he sees

as different modes of consciousness that had prevailed among particular groups at different periods of Brazil’s history. Freire views a magical (semi-intransitive) consciousness (associated with a kind of resigned acceptance of social problems) as dominant in rural peasant communities. And to this magical consciousness he opposes a critically transitive consciousness [...] characterized by depth in the interpretation of problems; by the substitution of causal principles for magical explanations [...] ; by soundness of argumentation [...] (Education: The Practice of Freedom).

In this project, the use of artworks is a way to rethink this opposition through working with objects that both contain causal principles and the concept of the magical dimension to some extent.

D3) IDEAS FOR POSSIBLE TRANSLATIONS