This paper was presented at the Mapping International Art Education Histories international conference, Teachers College, Columbia University, November 30 - December 2, 2023.

STUDYING, RECONSTRUCTING, REREADING, DIALOGUING, NETWORKING, REENGAGING, DISSEMINATING, RETHINKING, EXPERIMENTING.

We both form the artists’ collective microsillons (2023a) since 2005 and our practice is mostly taking place in Geneva, Switzerland.

We are developing socially engaged art projects in various contexts and in collaboration with different groups of people. Since our first projects, 20 years ago, we’ve placed our approach within the field of critical pedagogies and have therefore been avid readers of Paulo Freire.

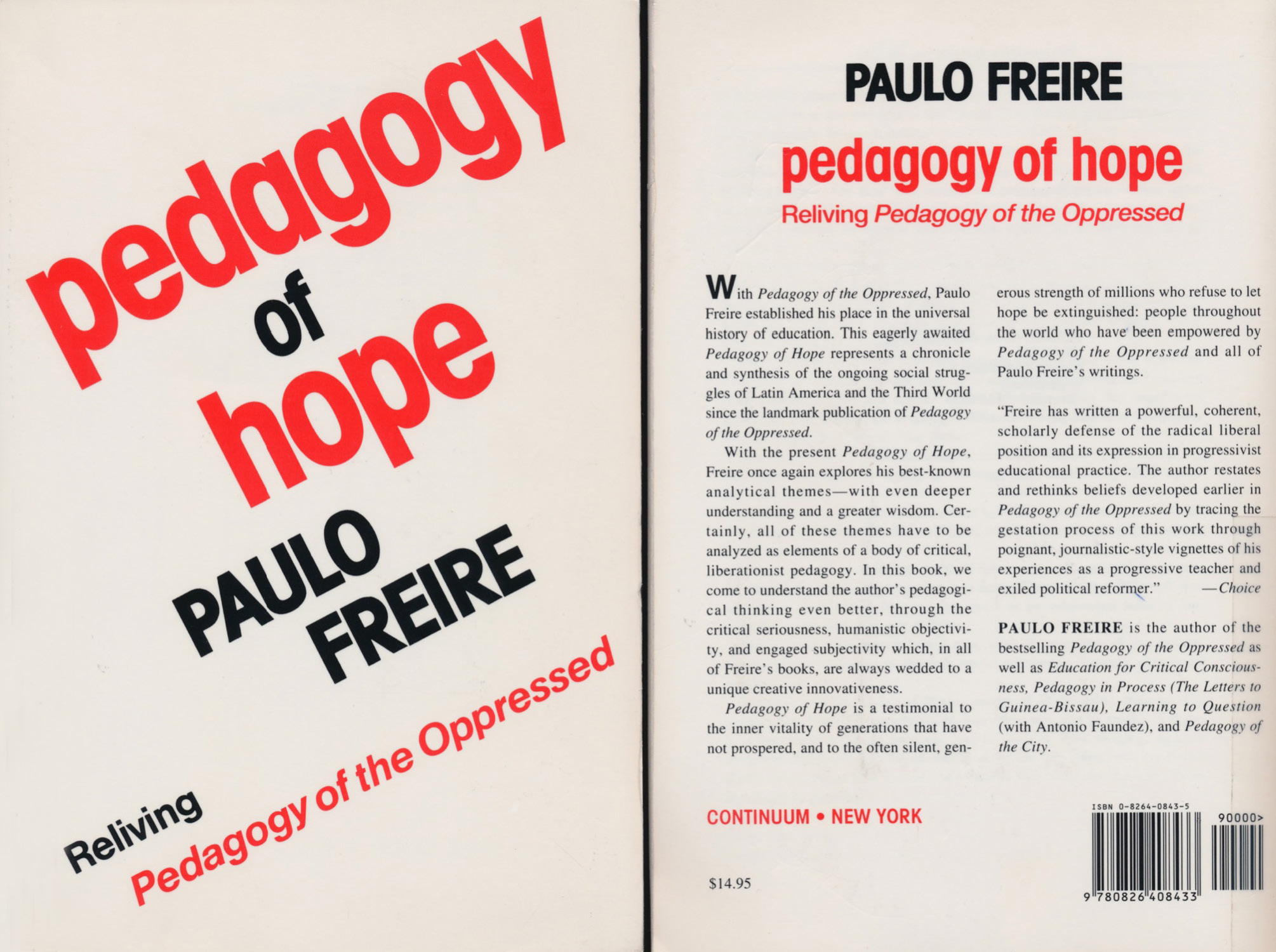

When we found out accidentally – a few years after we discovered Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 1970) because, as we will show it later, this was until very recently completely undiscussed in this city – that Freire lived for 10 years in Geneva, we decided to begin a research action based on the experiences and concepts of the Brazilian pedagogue with two main goals :

- First, we wanted to gather elements about the time he spent in Geneva and to re-inscribe our finding in the local history of this capital of pedagogy.

- Secondly, we aimed at finding ways to reinvent Freire’s pedagogy to develop today in Europe a multi-centered and less socially selective arts education.

In this presentation we will summarize some of the findings of the historical part of the research, talk about our methodology (at the border of social sciences and art) and then present a two-years long project in which we reinvented some tools of the Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

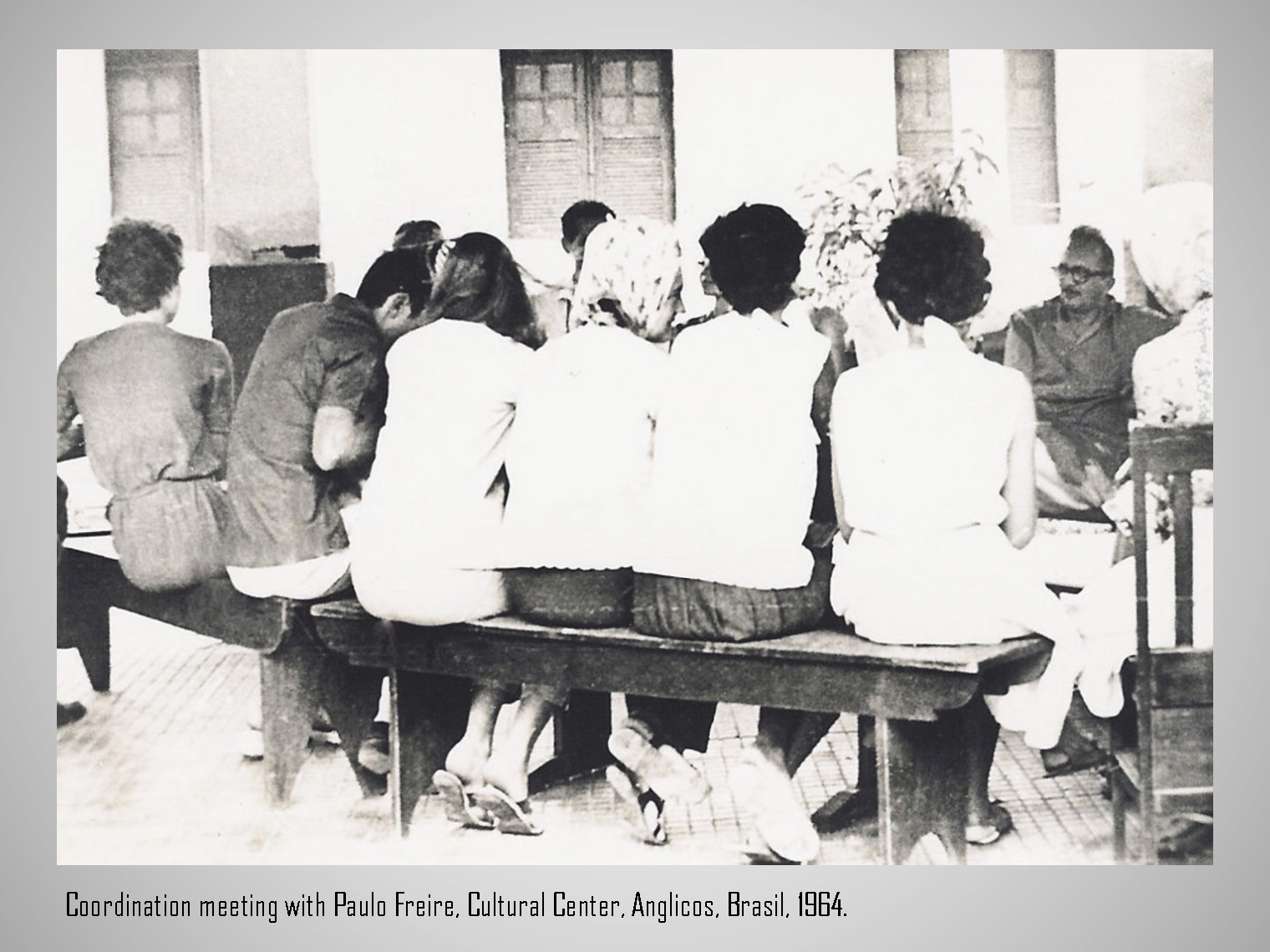

After having successfully experimented – since the beginning of the 1960’s – with his approach of literacy at a local scale, Freire is asked by the brasilian government to set up a national plan to teach two million people to read and write in 2000 ‘culture circles’ across the country.

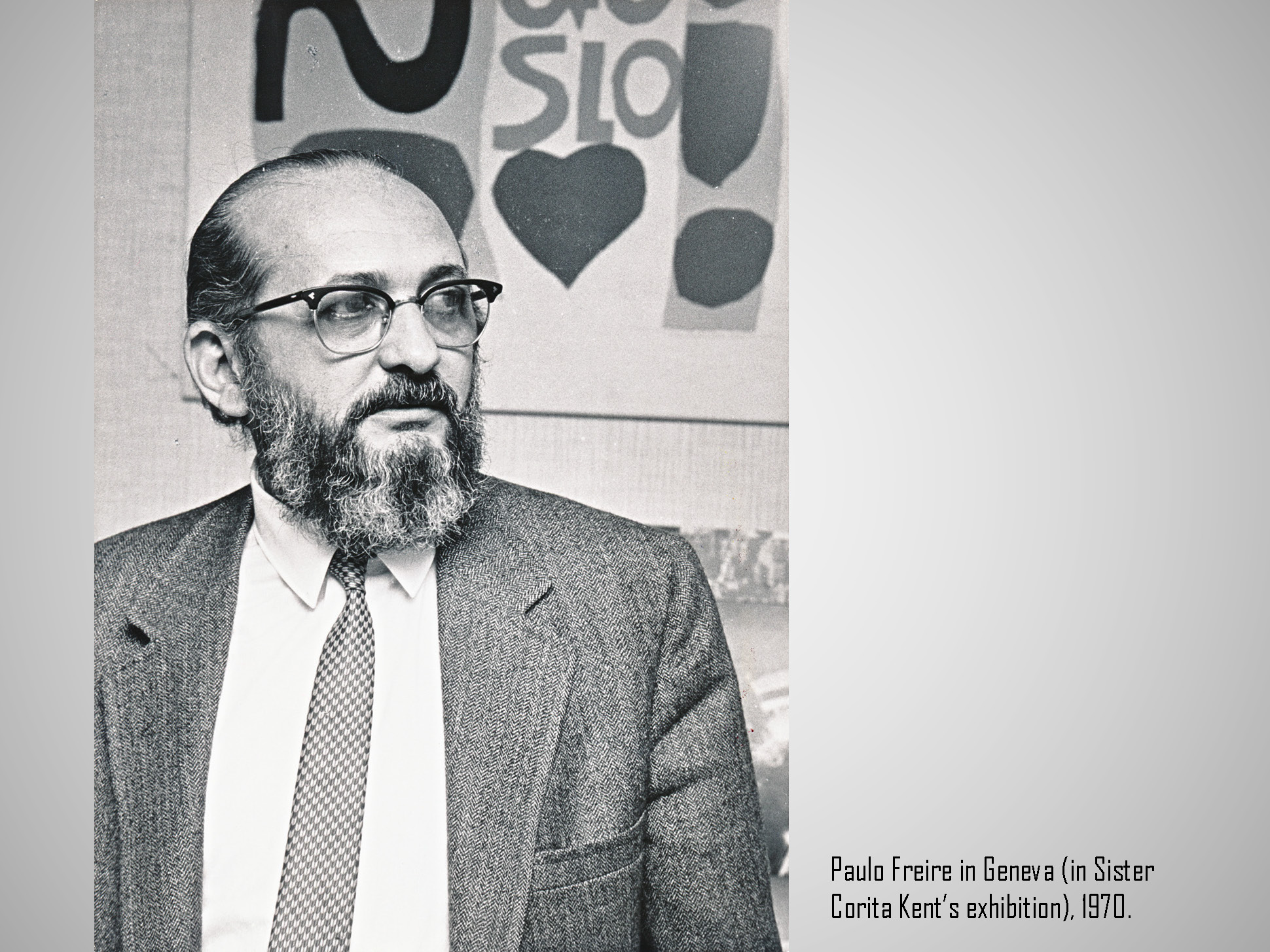

The military coup of 1964 drives him to flee Brazil and to later accept an offer of the World Council of Churches in Geneva to join their newly created Education Office. He saw this as an opportunity to support the decolonization movements in various countries through educational activities. Thus, in a letter he wrote after taking up his job, he quotes Fanon, saying:

He saw this position as a ‘world chair’ and, during the first half of his work at the World Council of Churches, between 1970 and 1974, he made over 75 trips outside Switzerland, on five continents.

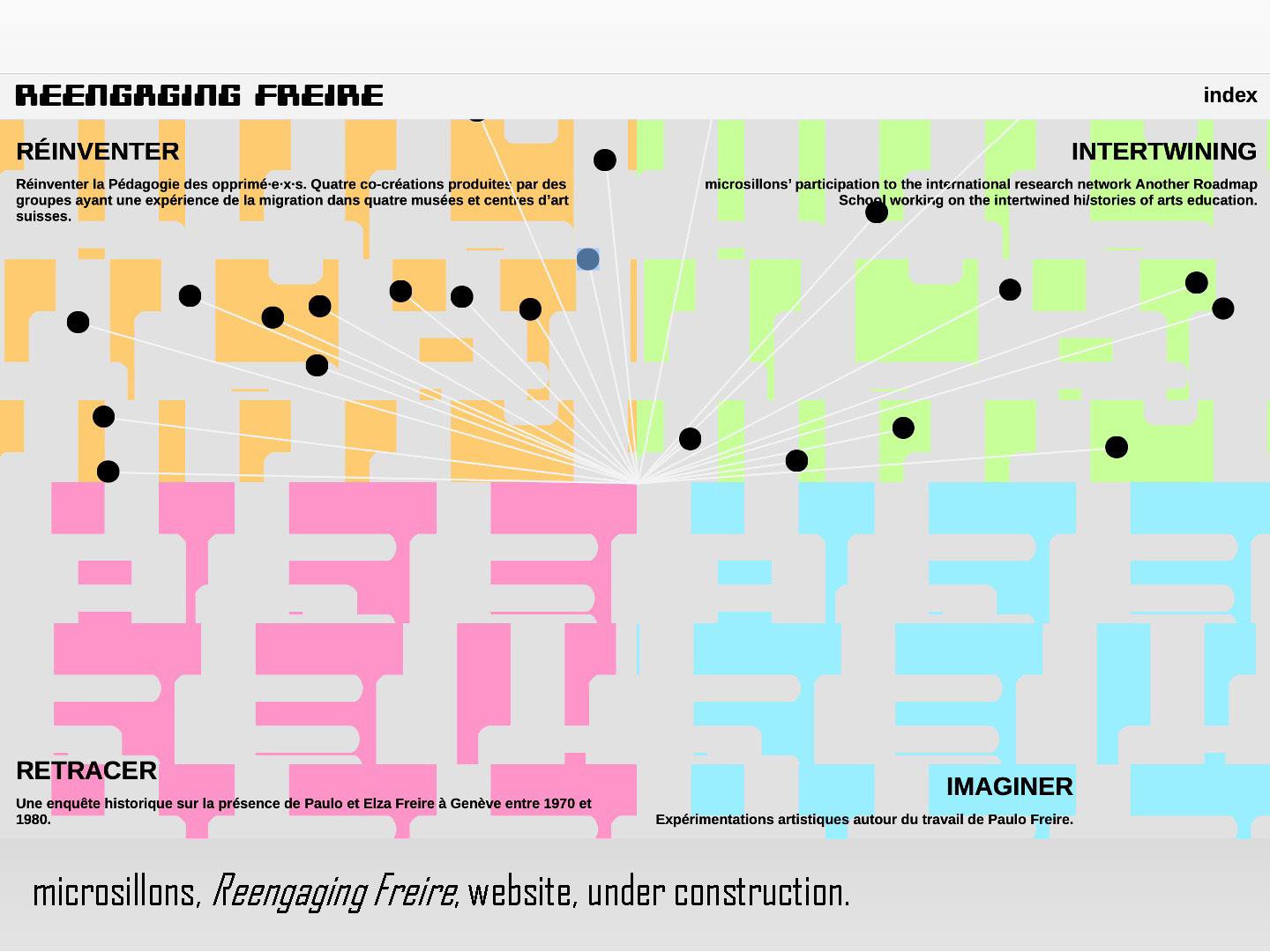

This is a map we produced from the archives, showing all the places he visited from Geneva, between 1970 and 1980. Freire is considered by many as one of the most important pedagogues of the 20th century but, until very recently, he was little discussed in the French-speaking world in general and in Geneva in particular.

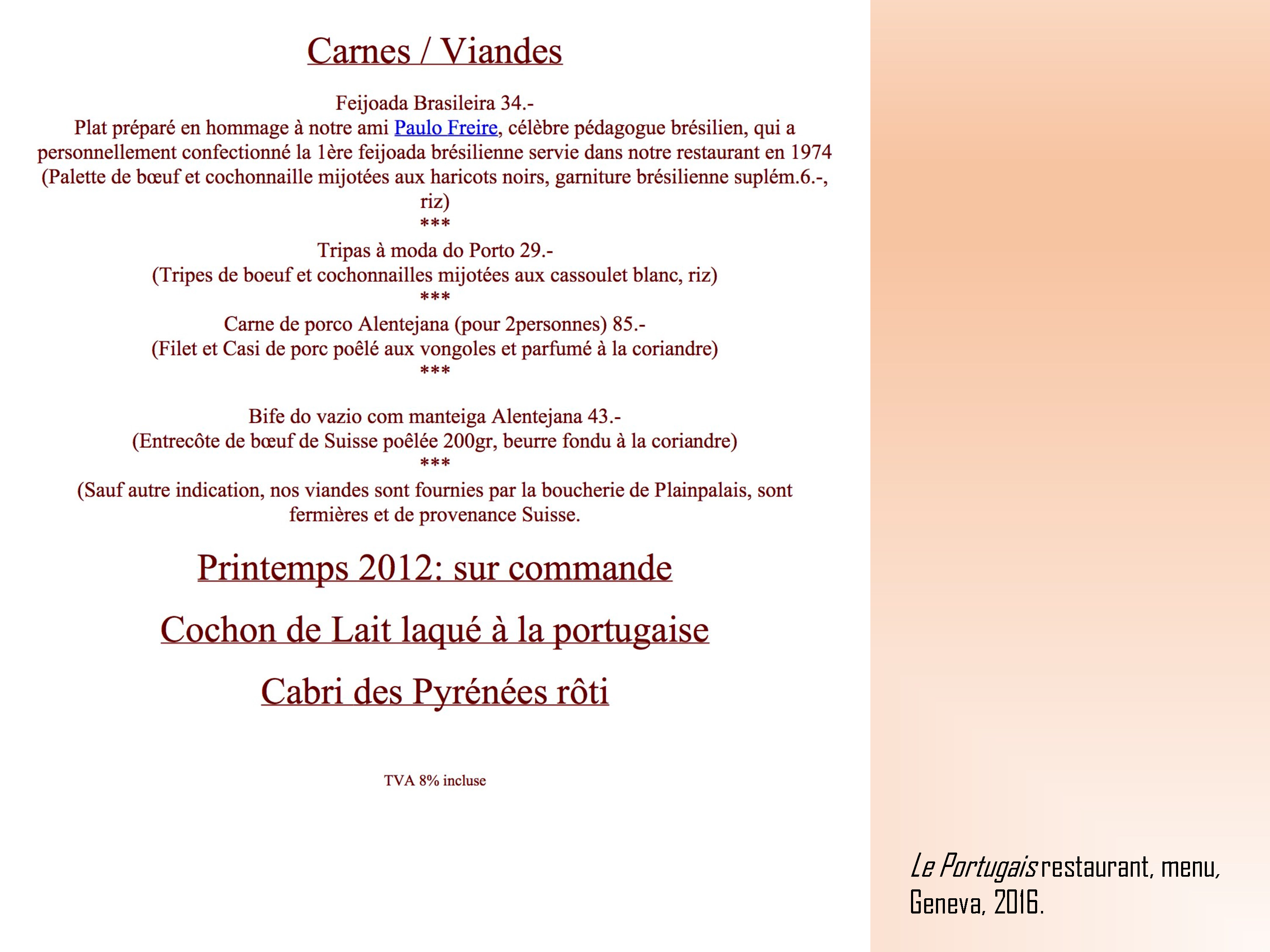

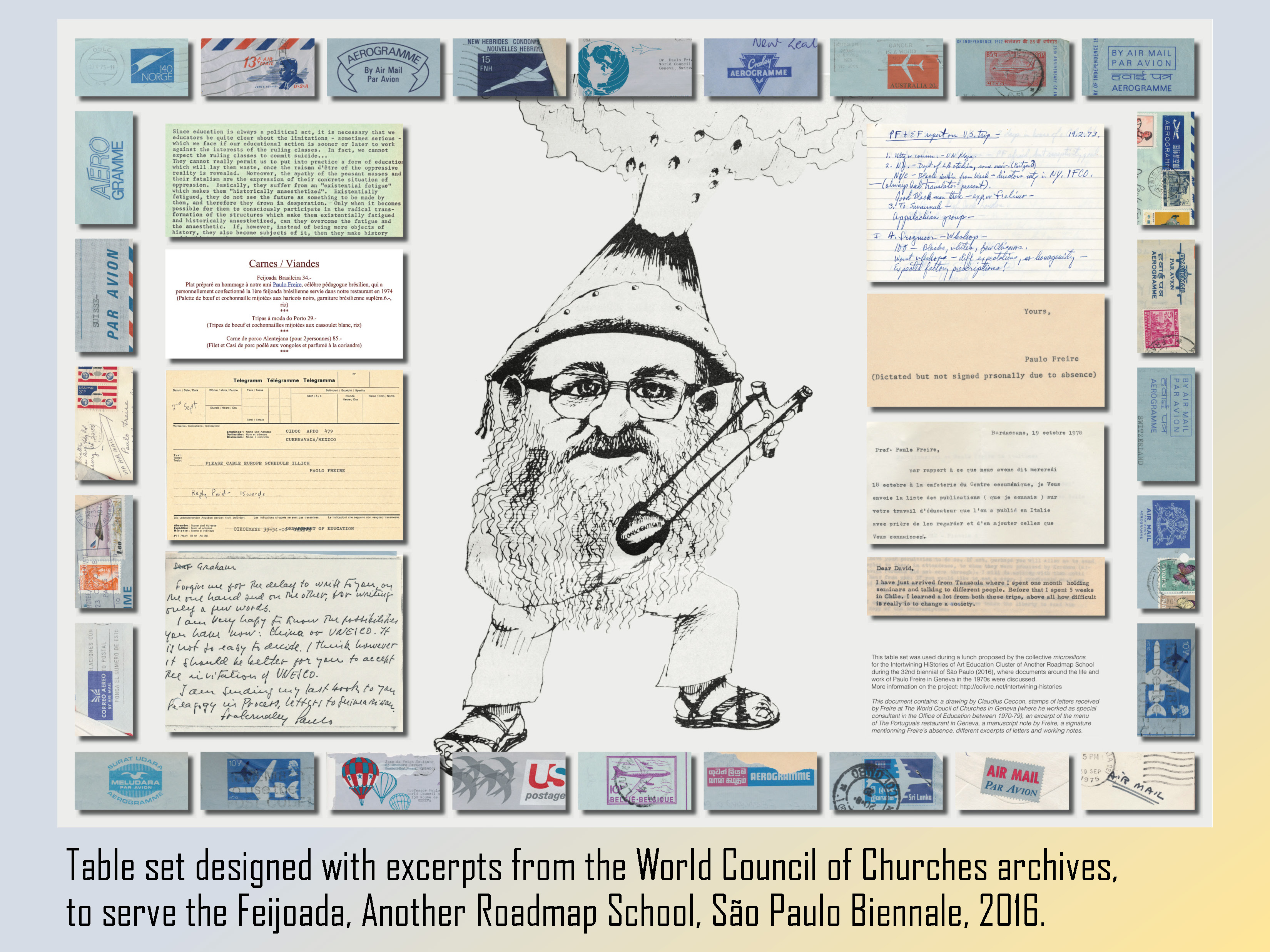

To date, the only reference to Paulo Freire that we have been able to identify in the public space of Geneva is a line on the menu of a restaurant, Le Portugais, which reads : ‘Feijoada, dish prepared in homage to our friend Paulo Freire, famous Brazilian pedagogue, who personally prepared the 1st Brazilian feijoada served in our restaurant in 1974’.

In order to reconstruct this history, in addition to a review of the available literature (in particular Kirkendall's (2010) research on Freire's years in Geneva and Pedagogy of Hope, in which Freire (1995) recounts several anecdotes about his life in Geneva) and an investigation of the archives of the World Council of Churches, we decided to write letters to various people who had worked with him in Geneva, requesting meetings.

We wrote our requests between the lines of excerpts of Freire’s texts selected for each person. This approach allowed us to meet two of his children, Cristina and Lutgardes, and Alberto Velasco, who was in dialogue with Freire for the development of a pedagogical action we'll present later on.

Exploring the World Council of Churches archives, we could retrace Freire’s activities from Geneva onwards: he gave lectures, took part in seminars and international meetings, acted as a consultant, and met groups involved in education and culture or politicians.

As it was an important aspect for him moving to Geneva, it was especially interesting to read how he responded to invitations from newly-formed African governments and worked closely with them to carry out literacy campaigns in former Portuguese colonies (Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé and Principe, Angola and Cape Verde).

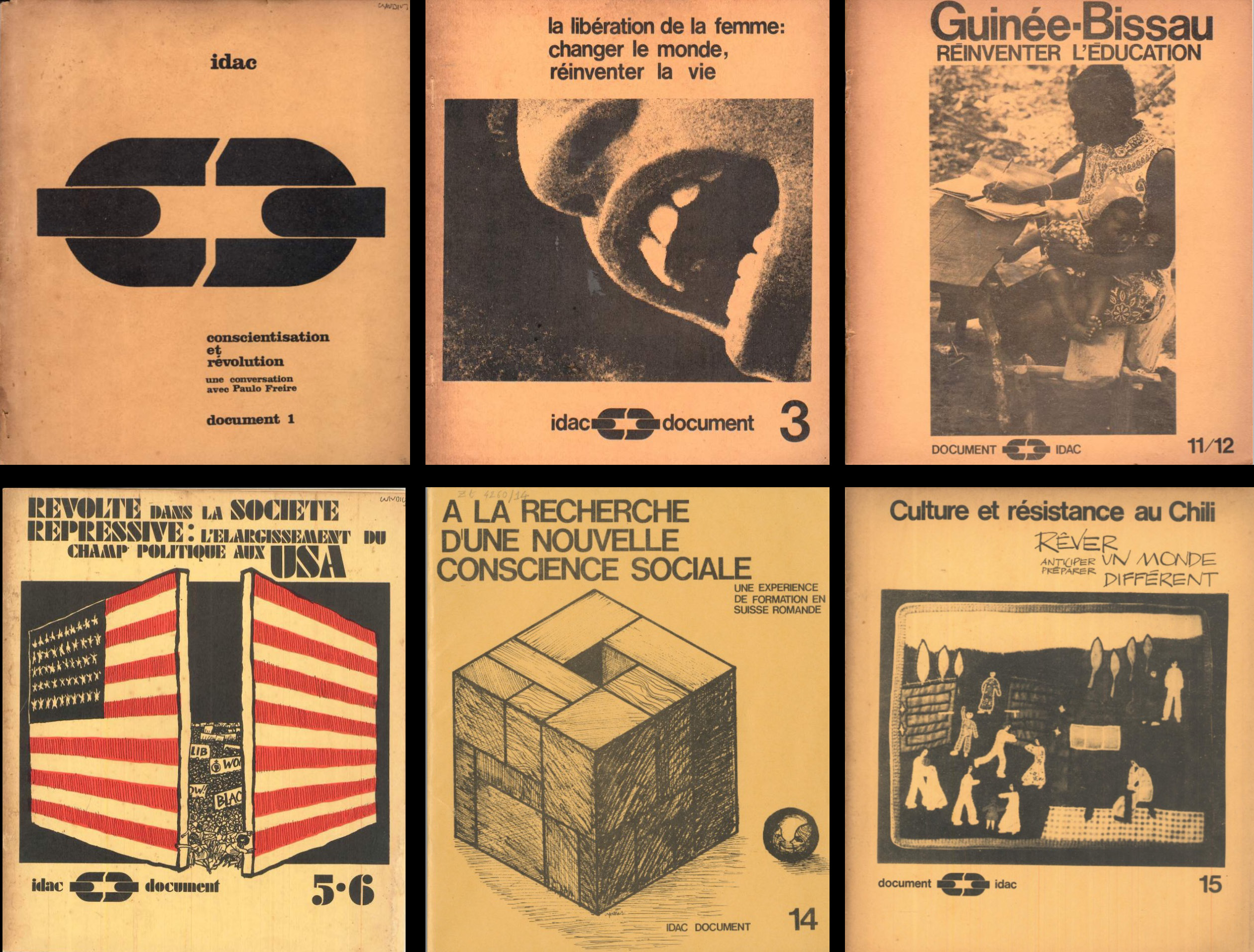

Some of these invitations were made to Freire not via the World Council of Churches but through the Institut d'Action Culturelle (IDAC), an organization he founded in Geneva in 1971 with other brazilian exiles and that gave him more autonomy. Here a selection of IDAC publications that shows the institute researches about education in different contexts (for example in Chile, in Guinea-Bissau but also in Switzerland) sometimes linked to actions directly run by Freire and sometimes more as an outsider research gathering reflections by politically engaged educators of the time.

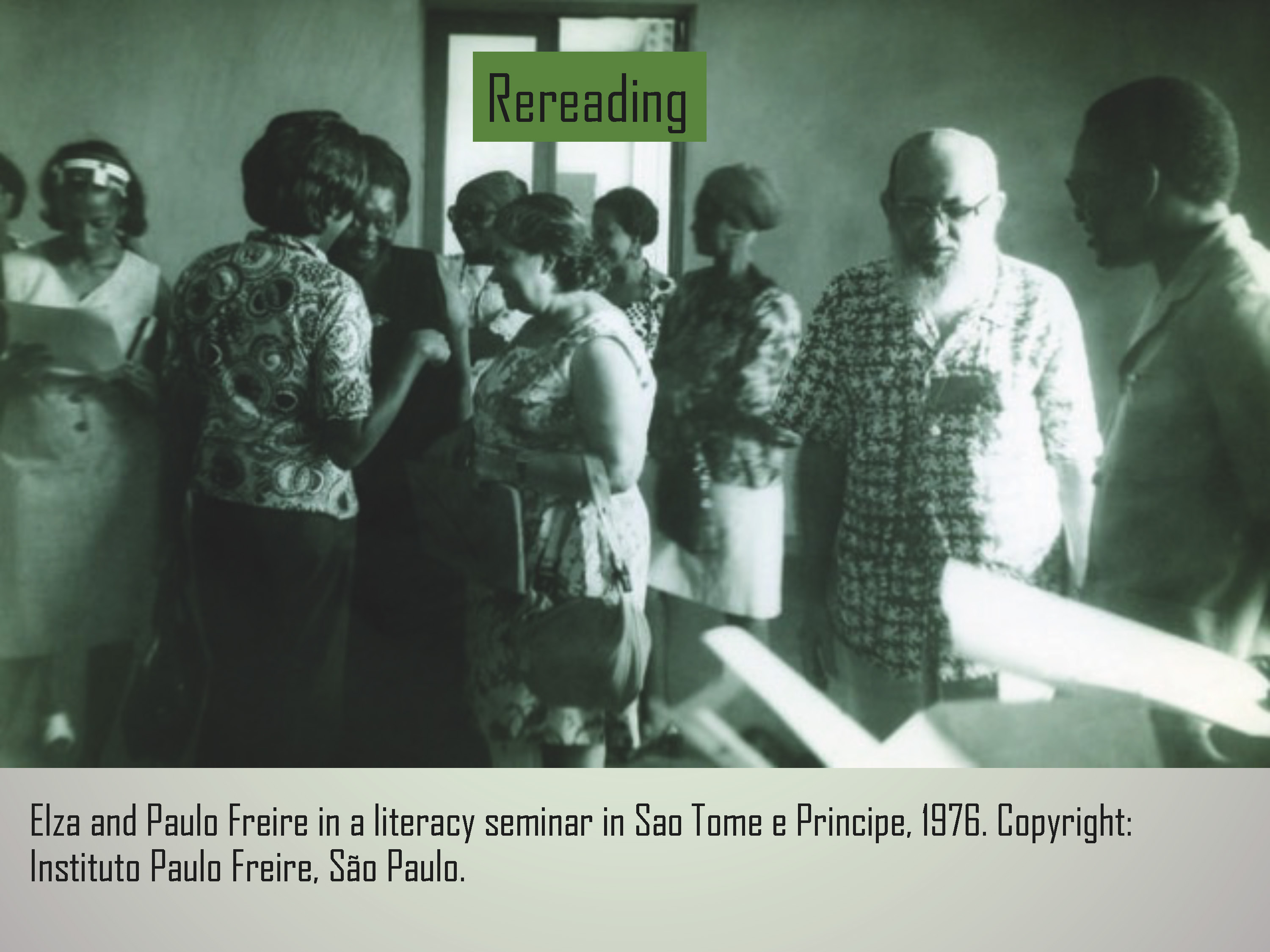

These projects in Africa also enabled him to travel and work with his wife Elza, a major change from his early years in Geneva, years during which he emotionally suffered from being so often far from Elza and his family. In the projects in Africa, Elza Freire's involvement was direct, and Paulo Freire spoke of, we quote, ‘programs that Elza and I developed in several African countries’ or, we quote again, of ‘training courses for educators that Elza and I coordinated [...].

Elza Freire wrote about the key role she played in the development of what has often been called the ‘Freire system’. Thanks to her experience as a school teacher, she made a major contribution to the development of the fieldwork attributed to her husband, particularly as regards the methodological aspects of literacy teaching.

Despite Elza and Paulo Freire’s recommendation to not apply any existing model but to work from the context, these programs in Africa have not always met with the expected success.

One of the main reasons for the difficulties encountered seems to have been the choice of Portuguese as the language of literacy, and hence the difficulty of breaking out of a framework where as Freire said ‘the shadow of a Western model of society looms large’. While Freire favored a bilingual approach (Creole and Portuguese), the government defended Portuguese as a necessary factor of national unification – adhering to the thinking of the revolutionary icon Amílcar Cabral (whom Freire greatly admired). Despite these difficulties, Freire writes, in an activity report, we quote :

Both the way in which Paulo worked in close dialogue with Elza and acknowledged her role, and the fact that they advocated for using non-colonial languages in the literacy programs, must be taken into consideration when reading the contemporary critics of Freire – calling in particular for a rereading of his texts through a feminist and postcolonial lense.

If these actions from Geneva are documented, our discussions with people who met him in the 1970’s were the only source to rebuild some of the actions he took part to in Geneva, mainly advising migrant workers and educators. We will now relate two of these actions briefly.

In 1971, Freire met up with three Science of Education students (Depierre et al., 1971) who were transposing his pedagogy to develop literacy courses with seasonal workers around Geneva. Initially, they took over existing French courses but, found that these were poorly attended, and that the material used was unsuitable because the thematic universe was disconnected from the workers' daily experiences, including the injustices they were constantly confronted with.

The students decided to develop their own literacy course in French and, through reading Freire's writings, invented a ‘methodological transposition’. They then had the opportunity to present their methodology to Paulo Freire at two meetings, in December 1970 and March 1971. He told them (Depierre et al., 1971: 59):

Based on this advice, the students will then develop and run a series of 12 two-hour sessions for five Italian workers.

As the students worked both with an existing language class and from their position as University students, this example resonates with the way we practice critical pedagogy ourselves, most often working within existing institutional structures. Their reinvention, in a dialogical way, of a pedagogical sequence, is very inspirational and aligned with the spirit with which we approach the Freireian tools.

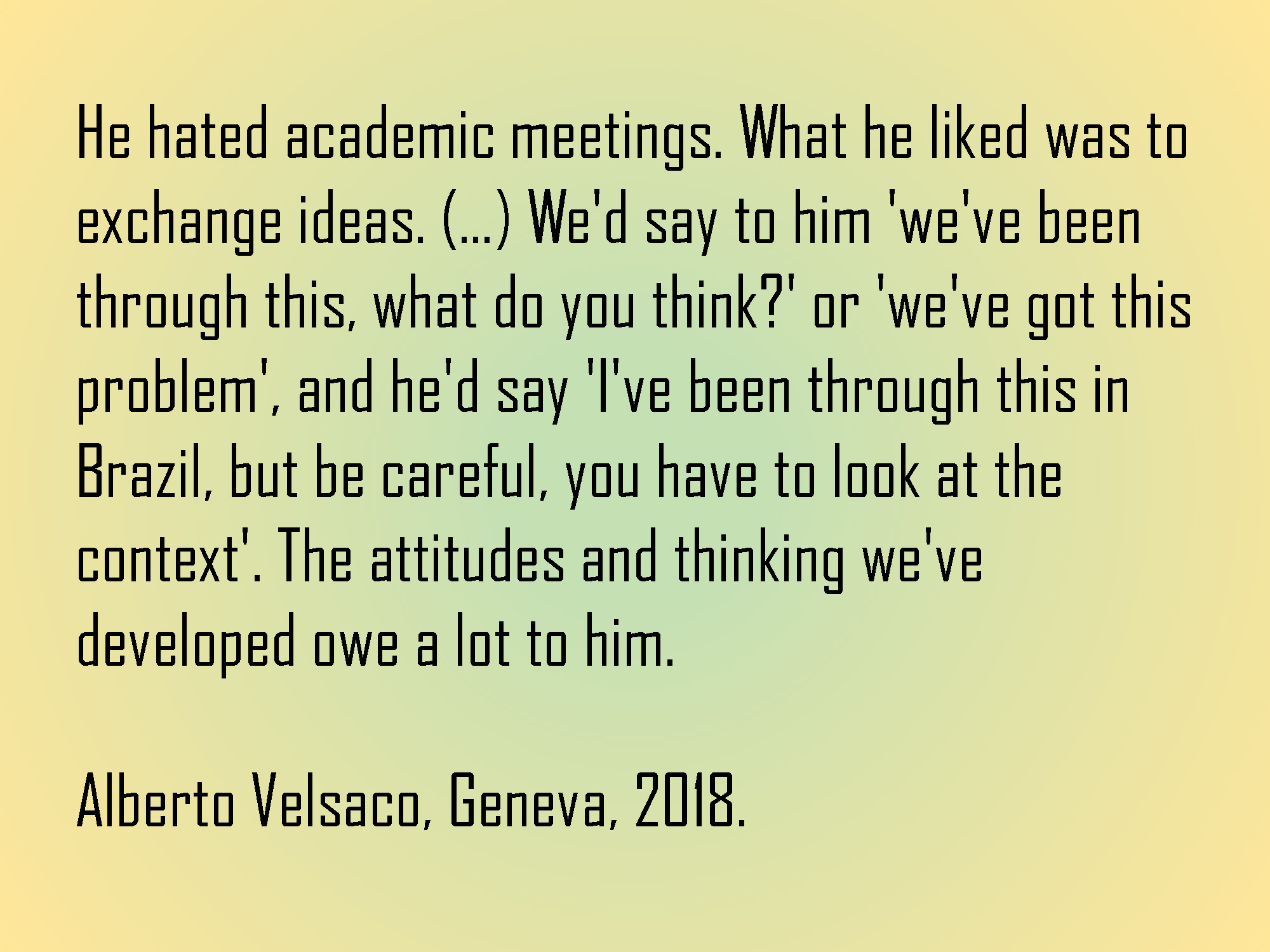

Meeting Alberto Velasco enabled us to learn more about another action – briefly mentioned by Freire in Pedagogy of Hope – an action with migrant workers in Geneva.

In Switzerland in the 1970s, seasonal workers were not allowed to reside with their families and the children who accompanied them could not go to school. Seasonal workers lived in harsh conditions and most of them had only a basic education.

Velasco, a Spanish national, arrived in Switzerland at the age of 13. Studying at university, he met a Spanish Catholic teacher, who had obtained the allocation of a small house in the center of the city for the Spanish community, where he gave evening classes in physics. This teacher asked Velasco if he could teach mathematics to young Spaniards. He agreed, and with a few friends, they began teaching several disciplines. Initially aimed at children, the courses soon became popular with parents.

The young volunteer teachers soon felt that they might not always use the right pedagogical tools. Knowing that Freire was in Geneva, they asked him for advice. According to Velasco, he was the only person who could help them because he had experience of working with the oppressed, he was sensitive to issues such as the shame of not knowing that some parents felt in front of their children, he spoke Spanish, and, finally, his position within the World Council of Churches could be useful to get support.

For months, almost every Saturday afternoon, informal seminars were organized between the beginning teachers and Freire. Velasco describes these meetings as follows:

Freire helped teachers to address the issue of age disparity among learners, and to establish a culture of dialogue and caring in the classroom. Freedom of speech was established, and mistakes were valued (as learning potential) rather than stigmatized. Within this framework of trust, political discussions became possible.

After two years, the participants were generally able to read, write and count and some were even taking an exam at the Spanish consulate in Bern to obtain a school certificate. Moreover, the experience also produced effects on the educators : Velasco recalls that this teaching activity was the most important experience in his life and this certainly played an important role for him later becoming a deputee for the city of Geneva. These multi-dimensional effects have been inspirational for our own practice.

We developed this research as artists and discovering these local actions of Freire has been an enlightening moment for us: knowing more details about the history, we felt equipped to enter dialogs with others and to engage with this material, in the same spirit of reinvention and adaptation than our predecessors.

To share these outcomes, we wrote articles that we could publish in Geneva University scientific journals (microsillons, 2022), gave talks in universities, educators conferences… We also produced a series of dialogical formats, based on our know-how of socially engaged artists.

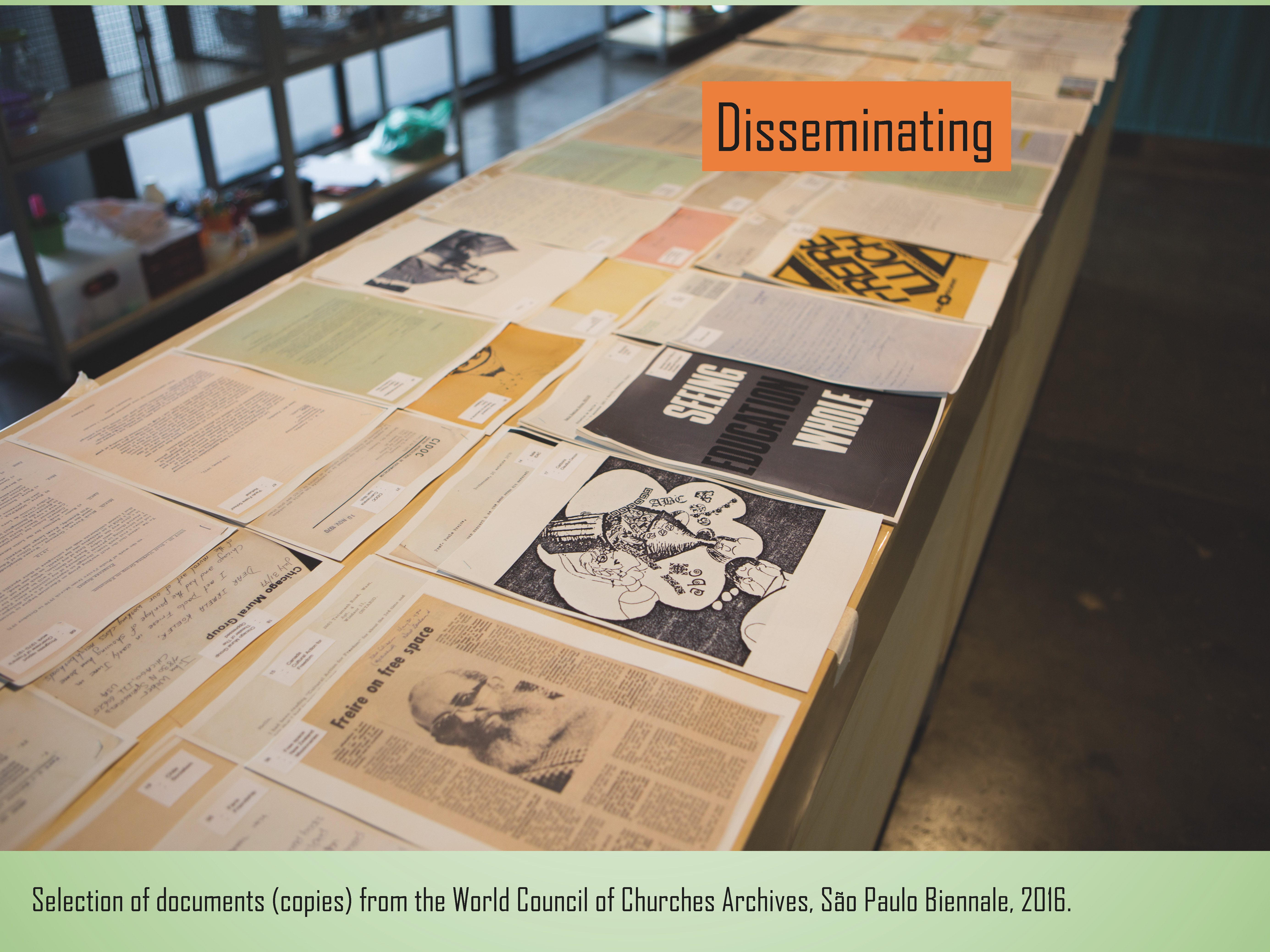

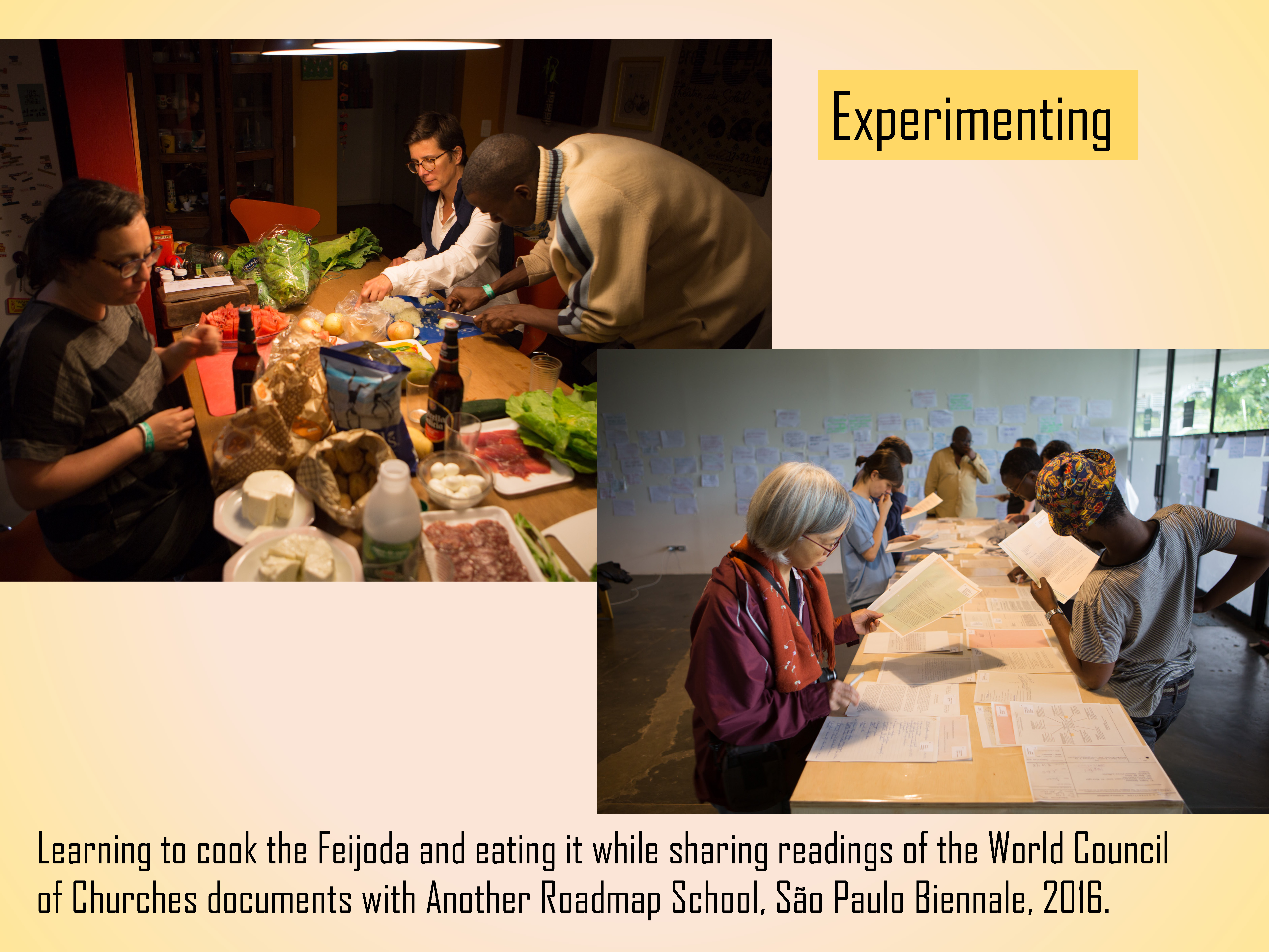

Among these actions, (with a team with Brazilian anthropologist and art curators) we learnt to cook and shared a Feijoada in the São Paulo Biennale to facilitate dialogue around documents from the World Council of Churches with critical gallery educators and artists from all over the world (microsillons, 2018), as part of the Another Roadmap School network. This practical and multisensorial activation of the archive opened the possibility to relate past and present and trace the genealogy of actual situations encountered by the participants. We designed a table set the serve with excerpts from the World Council of Churches archives, to serve the Feijoada.

Another action was to produce a bundle containing the answers of 75 cultural workers and educators to the question :

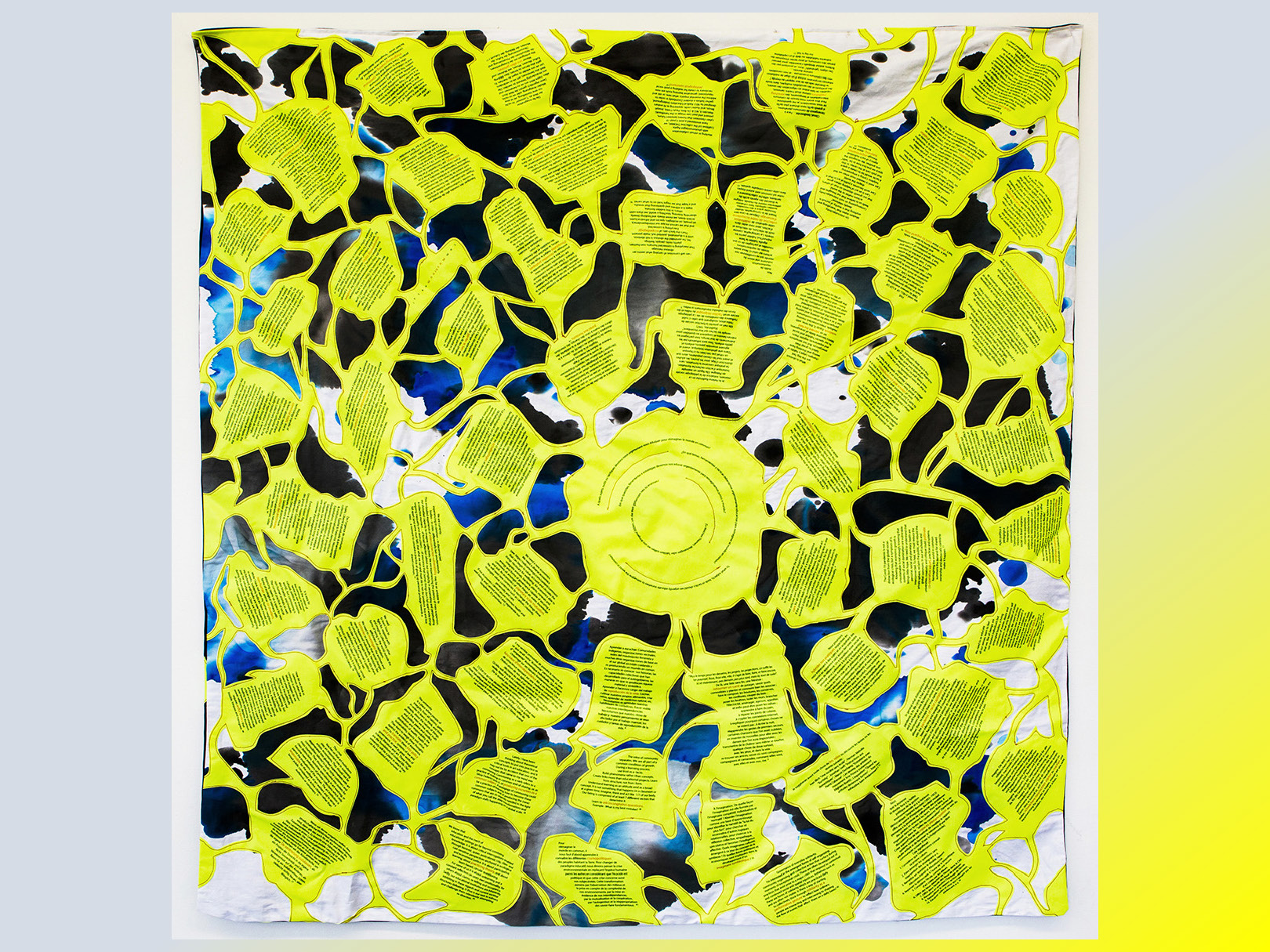

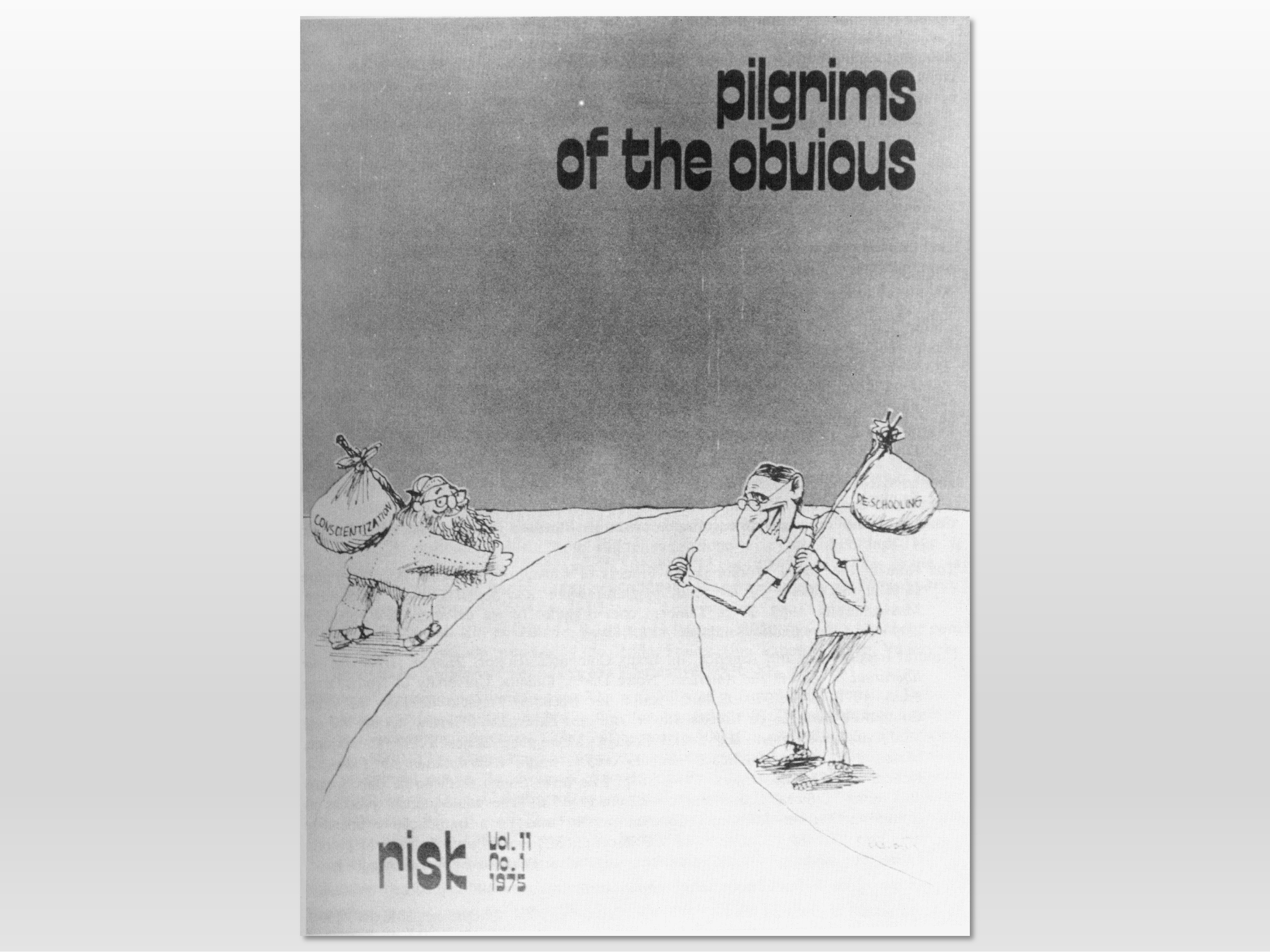

The bundle is made of layers of fabrics printed with contributions in five languages and is used as a metaphorical frame to continue the discussions with other people in different contexts such as art universities or cultural festivals, in the spirit of Freire’s idea of being ‘a vagabond of the obvious’ or ‘a pilgrim of the obvious’ the obvious being that there is no neutral education.

Convinced both of the topicality of Freire’s thinking, and of the necessity – as he himself calls for – to constantly reinvent his thinking, we then developed a project called Reinventing the Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

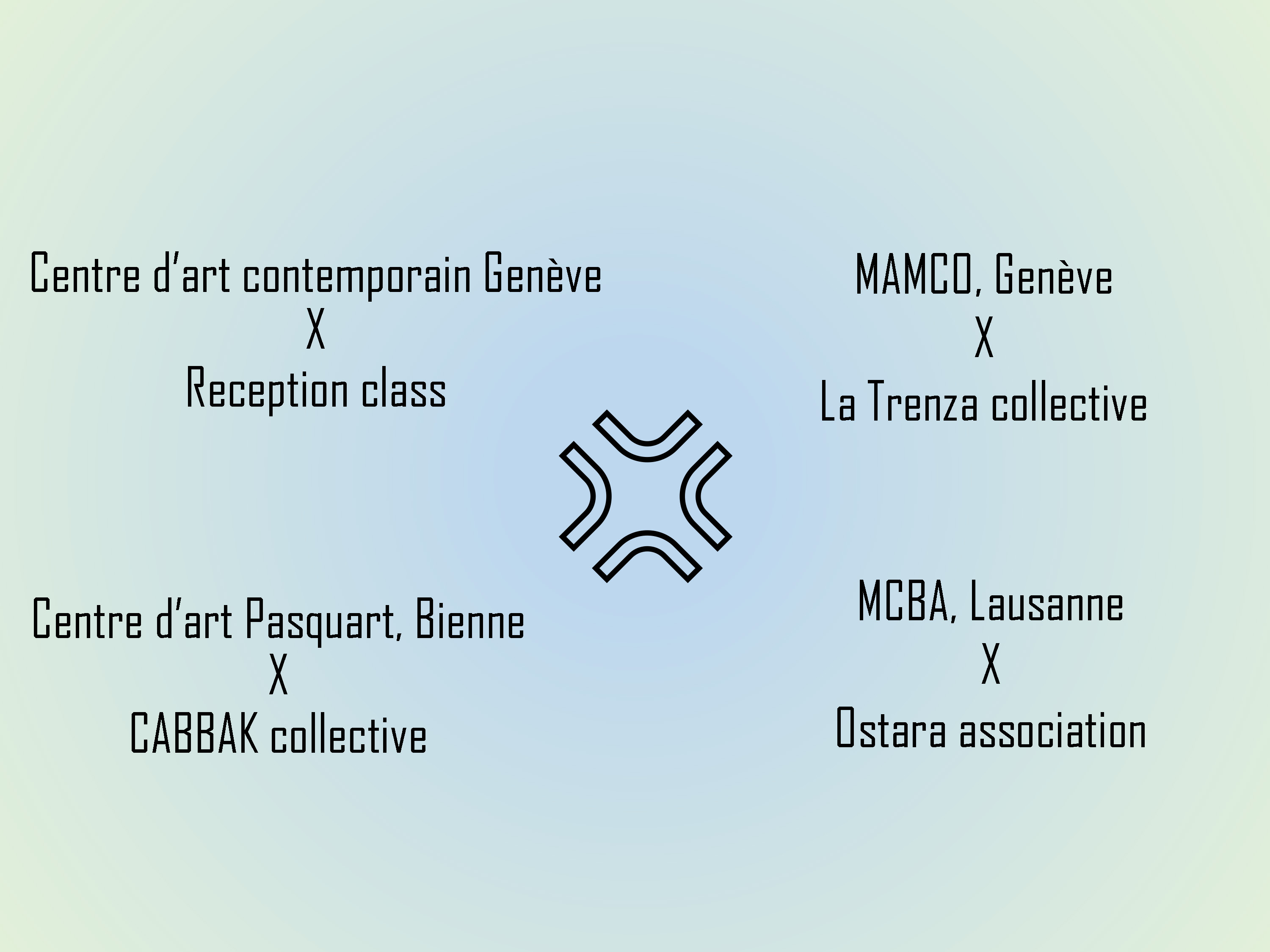

Conducted in the frame of our professorships at Geneva University of Arts and Design, this research is a collaboration with four contemporary art institutions in French-speaking Switzerland to develop experimental gallery education projects which, based on the principles of critical pedagogies, actively involve non-specialists in arts with a migration background in the production and public presentation of cultural objects in these institutions.

The first aim of the project is to change the production of discourse within contemporary art institutions by developing long term exchanges that promote a diversity of voices, of voices that are usually less heard inside these institutions.

The second objective is to provide a framework for gallery educators to gain autonomy in the production of discourse.

The third objective is to communicate tools to facilitate the development of future similar projects in other institutions or contexts.

The applicability and transferability (after re-reading) of Freirean notions in the field of cultural participation in contemporary art institutions were experimented within this project.

For example, the notion of generative theme – at the heart of Freire's Pedagogy of the oppressed – was key to our own project. Freire explains that, before the start of a pedagogical action, a transdisciplinary team of researchers identifies themes in the context in which it will take place themes that, once discussed, will facilitate – through their resonance with learners' everyday lives – both literacy and conscientization (Freire (1983) says ‘reading the word and reading the world’).

In our research project, this notion of generativity was challenged and reinvented : the themes were not predefined but sought after the start of the collaboration with the groups (four different groups, one in each art institution).

As a result, each project was very open-ended – so that a real dialogue could take place – and began with no constraints other than the idea that a cultural object would be produced by the group and presented publicly after a year of collaboration. No theme or form was therefore predefined for these productions. In each of the art institution, a gallery educator from the institution’s education department and one of the four members of the research team followed the project.

This logic of generativity was not always easy to sustain in institutions accustomed to planning in advance and working from thematic lines linked to their current exhibitions, nor with the participants, since such an open logic is rarely experiences, especially when one is invited to take part in a project. Nevertheless, in the course of exchanges and in their quest for specific generative themes, each group developed its own tools to foster this generativity.

These tools went from imaginary dialogues with people they admire to shared readings followed by workshops, from field surveys to wall diaries.

As a result, the groups involved were able to be truly co-creators of the projects, inventing their own ways of doing things and defining the subjects to be dealt with, without any pre-defined timetable, imposed format or imposed themes. These projects are therefore examples of ways to challenge – in cultural productions – the sole authority of curators, institutions’ directors (or even gallery educators, even if they are less often called upon to produce contents to be exhibited).

Another central aspect of the project was to counter what Freire calls ‘the culture of silence’, by getting groups that are usually not very visible or audible to speak out and to present – directly in the institutions – their own cultural productions:

- A reception class produced a film at the Centre d'art contemporain Genève, using the video overlay technique to stage imaginary dialogues around the issue of motivation.

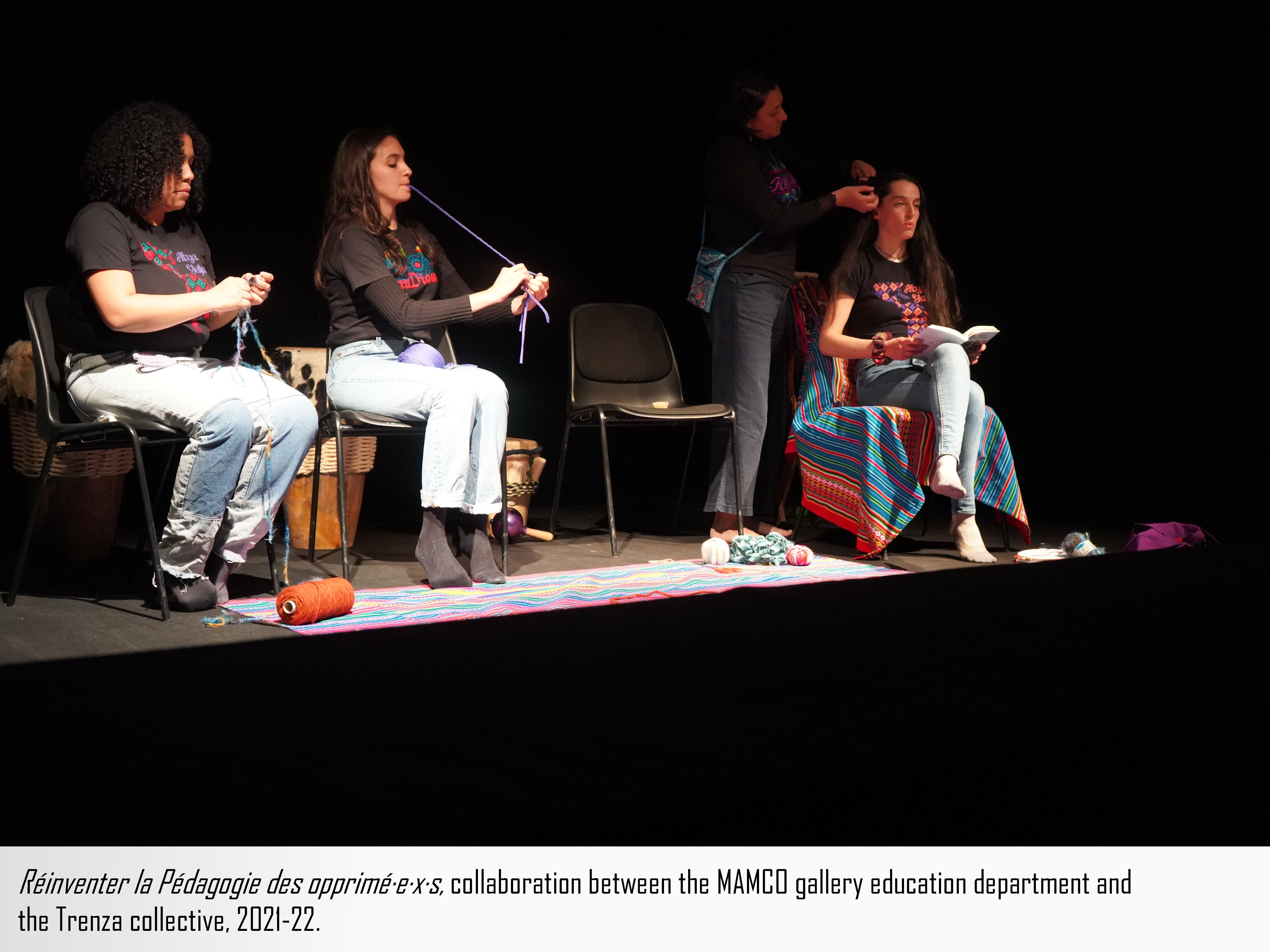

- A collective of migrant women from Abya Yala developed a performance at the MAMCO in Geneva that included reflections on colonial history and the hierarchy between different cultural forms.

- At the Pasquart art center in Biel, an Afro-feminist collective produced an exhibition, presenting a multicultural portrait of their city through the practices of its hairdressers.

- A group of migrant women learning French developed an alternative audio guide at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Lausanne, in which they commented on several works in the permanent exhibition based on their personal experiences.

Through these productions and the processes that made them possible, the roles that the museum or art center can play – beyond its conservation and exhibition missions – were discussed, and these institutions perceived by the participants as possible spaces for the self-managed sharing of knowledge and experiences, for the production of narratives, for conducting investigations and as a possible sounding board for their political struggles.

This experience confirmed the interest that a Freireian approach can have today for developing critical cultural projects, and we recognized the importance of not seeing his writings as the bearer of a pre-established method, but rather as a toolbox whose uses need to be constantly reinvented.

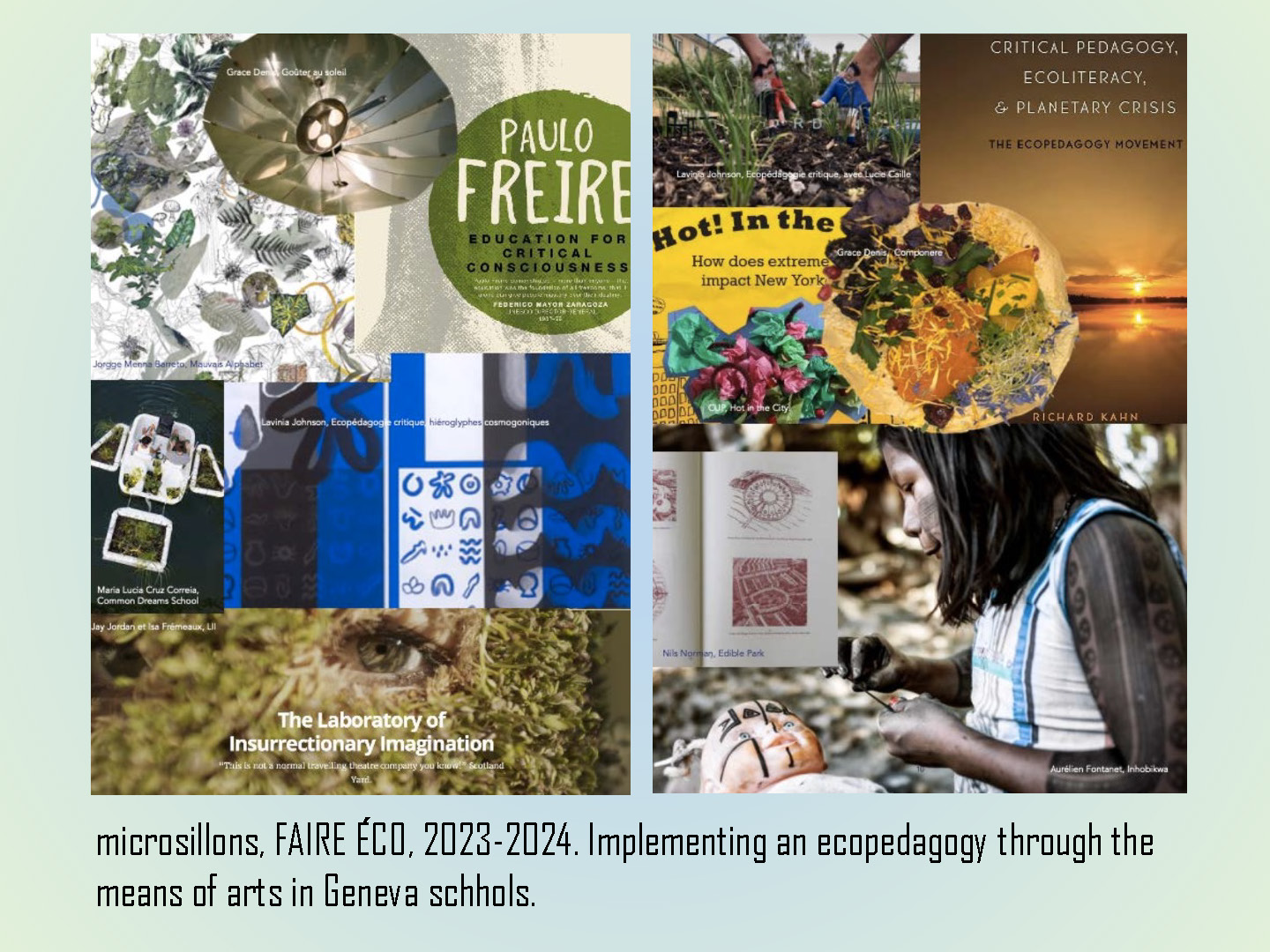

Pursuing this reinvention, and in particular developping a feminist and postcolonial rereading of it, we are now working on developing projects around the notion of ecopedagogy, which continues to anchor our practice in the critical pedagogies that, we believe, are absolutely necessary today.